The journal Food Policy just published a paper I co-authored with Ellen Van Loo and Vincenzina Caputo entitled, “Consumer preferences for farm-raised meat, lab-grown meat, and plant-based meat alternatives: Does information or brand matter?” I blogged about the working version of this paper this past fall when we finished the first draft, so I won’t re-iterate all the main findings (I should also note the paper at Food Policy is open access, and as such the results are freely available).

What I thought I’d do here is convey some results from the study that are not in the published paper but that are based on the models described therein.

First, a big unresolved question that often comes up when discussing the introduction and evolution of plant-based or lab-based alternatives is whether the the projected market share for the new alternatives is “stealing” sales from beef or rather drawing new people into the market who wouldn’t bought beef to begin with. Using the models estimated in our paper (in the “control” no information, no brand condition), I project that before any alternatives are introduced about 74% of consumers would buy ground beef on a grocery shopping trip (assuming the price is $5/lb) and 26% would refrain from buying ground beef. After the alternatives are introduced (at an assumed price of $9/lb), it is projected about 12% of shoppers would buy one of the beef alternatives. Thus, of the buyers of the new alternatives, I project about 57% (6.9/12.1) would have instead bought conventional ground beef whereas the remaining 43% (5.2/12.1) wouldn’t have bought beef in the first place.

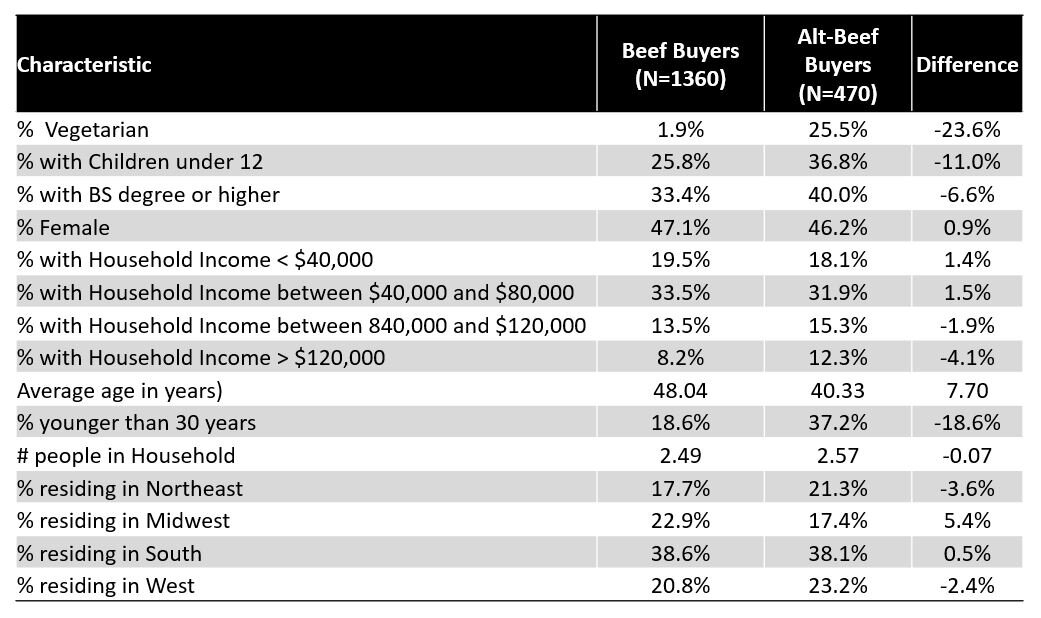

The paper in Food Policy shows some results related to the relationship between demographic characteristics and projections of which alternatives people would buy. To help make these findings a little more digestible, below is a table that shows the demographics of people predicted to choose conventional beef vs. people predicted to choose one of the beef alternatives (assuming all are the same price). Unsurprisingly, the people who are predicted to choose a beef alternative are way more likely to be vegetarian than are people predicted to choose beef. It is also the case that alt-beef buyers are much more likely to be younger and are somewhat more likely to have a college degree than conventional beef buyers. There are not big gender differences.

The table below shows a similar breakdown but instead of focusing on demographics, I report the importance consumers say they place on 12 different factors when buying food. Predicted beef buyers place greater importance on safety, taste, appearance, and naturalness. By contrast, people projected to buy one of the beef alternatives place more importance on novelty, environment, and animal welfare. (note: in general differences greater than about 0.1 are significantly different than zero at the 0.05 significance level).

Finally, one of the most interesting results of the survey were responses to open-ended questions we asked about people’s perceptions of the competing products. Here are some word clouds Ellen created.

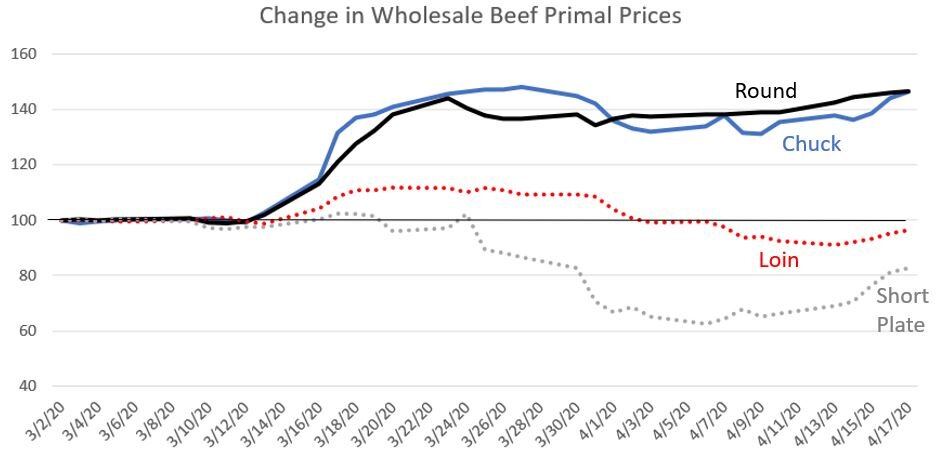

These data were collected about a year and a half ago, and given the novelty of the products, it is possible perspectives have changed, particularly following COVID19. Fortunately I have some follow-up work planned with Glynn Tonsor and Ted Schroeder. Be on the lookout for some of those results hopefully some time this coming fall.