My wife likes to buy cosmetics products from a company called Paula's Choice. One of the things she likes about the company is that it reports on the scientific testing it does on its own products and that of its competitors.

In any event, my wife alerted me to an interview with the company's owner, Paula Begoun, which I found fascinating. It seems the cosmetics world is grappling with many of the same issues as the food world.

Paula was interviewed on radio by another cosmetic's industry insider: Karen Yong. Here are some excerpts from the transcript when the discussion turned to "natural" and "organic" cosmetic products:

Paula Begoun:. . . On the other side of the coin one of the things many cosmetic companies have to deal with is the fear mongering around the evilness of cosmetic ingredients which I've written about extensively and I know you have opinions on.

How are the cosmetics companies, the Lauders, the Shiseidos dealing with this fear mongering that the organic natural cosmetic world is putting out there.

Karen Young:It's frightening and it's probably the biggest thing that I'm confronted with right now. I'll try to narrow it down a little bit because as you know it's a huge category.

Paula Begoun:Wait, you're not frightened about the ingredients, you're frightened by the influence…

Karen Young:The press.

and

And the other piece of that as you alluded to is the whole natural organic green-washing thing, which is so confusing that even those of us who are supposed to understand what's going on here, it's really, really difficult.

Paula Begoun:I'm often shocked by the women really do believe – I get asked it all the time. “Should I be scared of what I'm using. Is it killing me? And I'm using this natural product.” And I know what those products contain. That's what we do for a living here at Paula's Choice is we review everybody else's products and look at what the formulas are and what they contain and what they can and can't do for skin.

00:20:36And lots of natural ingredients that show up in natural products are bad for skin. And I'm looking at this woman telling me I'm so scared other products are killing me and I'm going, yeah, I know, but you're breaking out, your skin is red. I know what you're using isn't protecting you from aging, or sun damage, and on and on. And they're frightened of everybody else's ingredients except the company that is dong the fear mongering.

00:21:00Of course, they never tell you what problem ingredients their products contain, but, yeah, it's an insane – so, how are the Lauders and the Shiseidos, I mean, Lauder is not going to give up. They're not going to go all natural. They know that all natural isn't going to fly for skin. And lord knows an elegant product without silicone is almost impossible. And there's nothing wrong with those ingredients. What are they doing about this aside from I know that the industry went away from parabens.

and

Paula Begoun:Actually, you know, it's interesting, because one of the things that happens when you start making “all natural products” is you increase the need for higher levels of preservatives.

Karen Young:Preservatives!

Paula Begoun:And there aren't any so-called natural, although even the natural preservatives when you have to increase it that much, then you're getting irritation. Preservatives kill things. That's what they do.

Karen Young:Absolutely.

00:24:37You're getting irritation and possibly you're making it more difficult to stabilize the formula.

Paula Begoun:You know, we're just reviewing a product line that, you know, we haven't run into this in a long time. A lot of the natural product lines, while the formulas may have issues in terms of irritating ingredients and jar packaging and fragrance, and I'm going to ask you about jar packaging in just a second, but one of the things that we haven't run into in a very long time is a company claiming that it's all natural but it actually isn't, it actually uses synthetic ingredients.

00:25:15This is one of the first times in a while I would say in the past, I don't know, three, four years that we actually ran into a company that is lying through their teeth. Their products are about as natural as polyester. Do you see that – do you run into that in your research?

Karen Young:Yes.

Paula Begoun:Yeah, you see that, too.

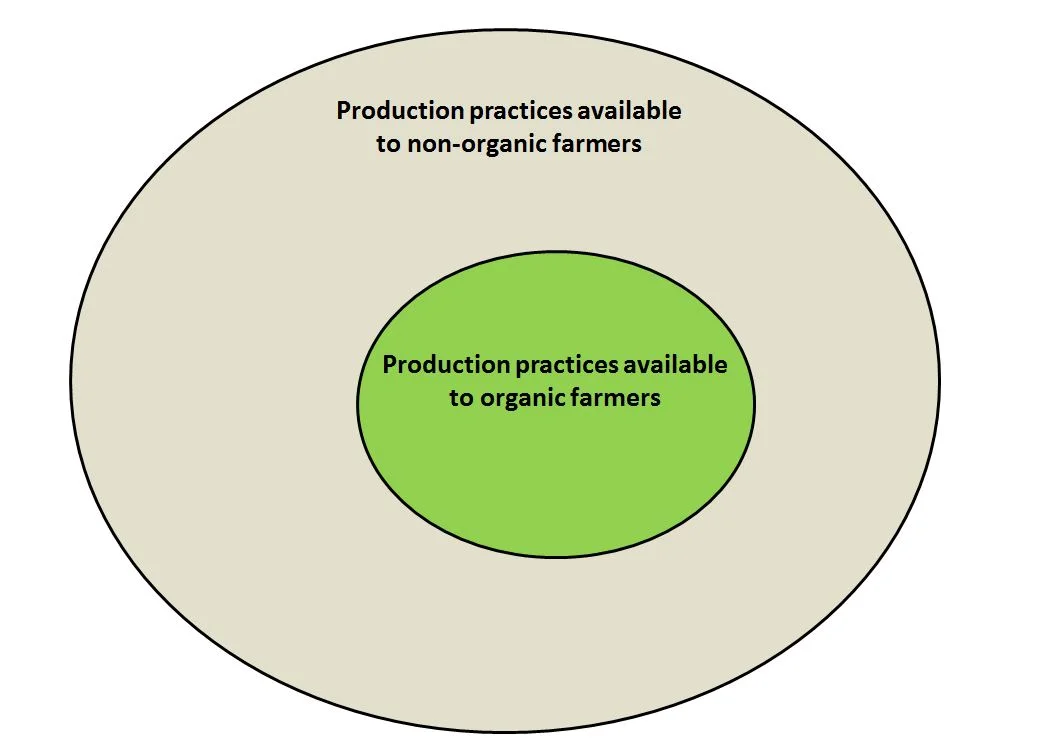

Karen Young:Because as you know there is no definition for natural. It's completely arbitrary. You can use the word anyway you like. And consumers, as you mentioned earlier, consumers are incredibly confused about what does natural mean and what does organic mean. I mean, that theoretically is defined by the FDA and consumers really don't understand that either.