The December 2015 edition of the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) is now out.

Some observations from the regular tracking questions:

- Compared to last month willingness-to-pay for all products, particularly beef products, was up.

- There was a sizable drop in the proportion of respondents who say they plan to eat out more in the next two weeks.

- There was again a big spike in awareness and concern for E. Coli and Salmonella, likely as a result of the publicity surrounding the Chipotle outbreaks,

- There was a large increase in visibility of GMOs in the news in the past two weeks.

- The fraction of respondents who said they suffered from food poisoning doubled compared to last month.

Three new ad-hoc questions were added this month.

The first set of questions dealt with consumers perceptions of different animal welfare labels. Respondents were asked: “Which of the following labels, if seen on a meat or animal product in a grocery store, do you think would indicate and assure the highest and lowest levels of farm animal welfare?”

Participants were then shown images of nine different labels (randomly ordered across surveys) and were asked to click three labels and move them to a box indicating the highest level of animal welfare and then click three of the labels and move them to a box indicating the lowest level of animal welfare.

Here's what we found.

More than half the respondents put the following three labels in the highest welfare category: Certified Humane, Animal Welfare Approved, and American Humane Certified. Two labels, 100% natural and non-GMO verified had nothing to do with animal welfare and they were generally ranked neither high nor low. The largest percentage of respondents placed the Tyson brand label in the lowest animal welfare category, but it had more “highest welfare” category placements than Global Animal Partnership or Food Alliance Certified. The Global Animal Partnership label (which showed a Step 4 rating) was most likely to not be placed in either

the the highest or lowest welfare categories.

The next set of questions were added to investigate issues related to consumer aversion/acceptance of GMOs and perceptions of corporate involvement and control. The questions came about as a result of a Q&A after a talk I game in Amsterdam last month at the Conference on Coexistence between Genetically Modified (GM) and non-GM based Agricultural Supply Chains. In particular, Norbert Wilson from Auburn followed up and helped devise the following questions.

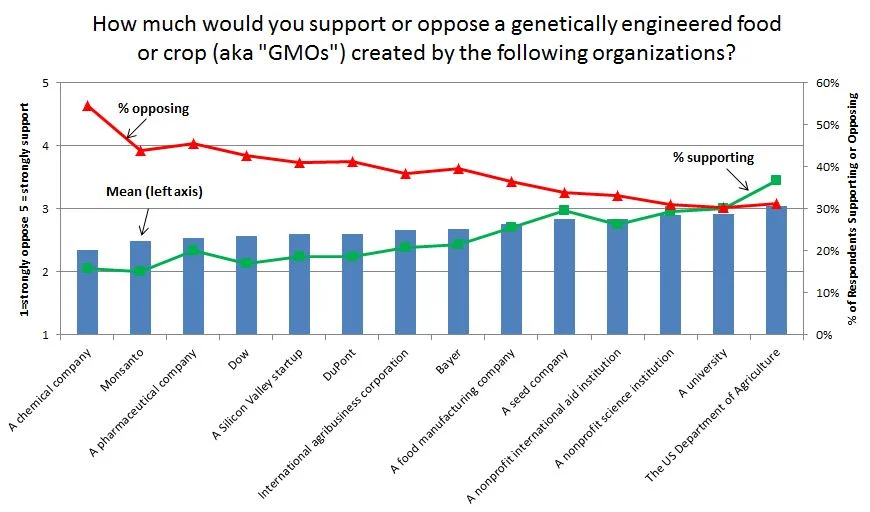

We first asked, “How much would you support or oppose a genetically engineered food or crop (aka “GMOs”) created by the following organizations?” Then, fourteen different entities were listed (in random order across respondents), some of which were specific company names and others that were generic entities. Respondents replied on a 1 to 5 scale ranging from strongly oppose to strongly support.

GMOs from a chemical company, Monsanto, and a pharmaceutical company were the were least supported. GMOs from a non-profit scientific organization, a university, and the USDA were most supported. For the latter two categories the percentage of respondents supporting equaled or exceeded those opposing.

Finally, the last question asked, “Of all the possible benefits that arise from the genetically engineered (or “GMO”) food and crops currently being produced, what percent of the benefits do you believe go to the following entities?” Eight different groups were listed (in random order), and respondents had to allocate 100 points across the groups.

Respondents thought seed, chemical and farm input suppliers received the largest share of the benefits (at 17.7%) followed by governments and food processors (each at about 15%). Farmers were next at almost 14%. At the bottom were consumers (10.6%) and universities (8.7%).

Who consumers think benefits from GMOs appears to have some relationship with concerns and acceptance of GMOs. Recall, one of our standard questions asked every month is how concerned that GMOs pose a food safety risk in the next two weeks. When we calculate correlations between GMO concern and the distribution of benefits from above, there are some statistically significant correlations. The larger the perceived benefits to consumers and farmers, the lower the perceived concern about eating GMOs.

Similarly, the correlations between the average level of support for GMOS made from the 14 entities indicated above and perceptions of who benefits are shown in the following table. People who think universities and consumers benefit more from GMOs are more likely to support GMOs. By contrast, people who think seed, chemical, and farm input suppliers and governments benefit more are less likely to support GMOs.