Bailey Norwood and I have a new paper forthcoming in the journal Ecological Economics that seeks to identify how much money vegetarians spend on food relative to meat eaters. This issue is of interest because food costs are often a reason touted for reduced meat consumption. The argument is that meat is expensive and thus eschewing meat (or participating in meatless Monday, for example) will save you money. Here additional motivation for the work:

“The implications of the dietary costs of vegetarians goes beyond the impacts on one’s wallet—it will help determine the carbon footprint of meat, dairy, and eggs. If a vegetarian spends less on food, what do they do with their remaining income? And do those other purchases have higher or lower carbon impacts? If vegetarian diets have both a lower carbon footprint and a lower price-tag, then one cannot really determine the carbon impact of becoming a vegetarian without accounting for how those food savings are spent. If vegetarians spend 15% less on food but use those savings on a plane flight, then their overall carbon footprint might rise. Indeed, Grabs (2015), who labels this a “rebound effect”, found that half of the carbon footprint reduction attributable to a vegetarian diet actually disappeared after accounting for the carbon effects of the remaining expenditures. Like Berners-Lee, Grabs infers the expenditure patterns of vegetarians using an amalgamated dataset using inferred (rather than observed) prices paid by each individual, where US data on the differences between the diets of vegetarians and omnivores based on Haddad and Tanzman (2003) is assumed to hold true for Swedish citizens.

Even if the cost of food isn’t a prime reason typically given to adopt vegetarianism, environmental impacts are, and what Grabs shows is that the two items are related. A better understanding on the relationship between vegetarian diets and food expenditures is thus warranted not just because it helps us understand the monetary consequences of altering our diets, but the environmental consequences as well.”

We used data from my monthly Food Demand Survey (FooDS) to determine how much vegetarians report spending on food at home and away from home compared to meat eaters. The analysis is complicated by several factors. First, many of the people in our survey who say they are vegetarian or vegan actually choose a meat item in a prior portion of the survey that simulates a shopping experience (perhaps because someone else in their household eats meat). Thus, we conduct our analysis separately for "true" vegetarians (about 2.2% of the sample) and "partial" vegetarians (about 3% of our sample). Secondly, vegetarians/vegans differ from meat eaters in a variety of ways, such as gender, political ideology, income, etc. This raises the question of whether differences in gender, income, etc. explain differences in spending patterns or whether it is dietary choices. Moreover, while one can change from from a meat eater to vegetarian, one cannot (easily) change from male to female, very conservative to very liberal, or black to white. Thus, we conduct several counter-factual simulations where we ask what happens if one converts to vegetarianism but retains their prior demographic characteristics vs. someone who differs in both regards.

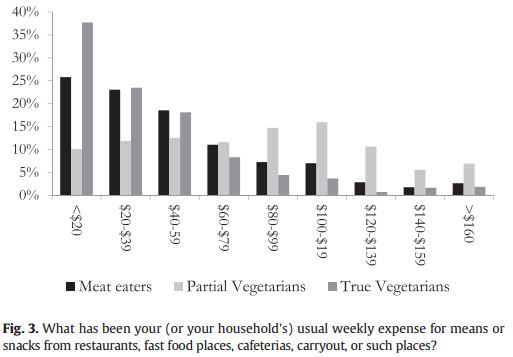

Here are some summary statistics on distribution of spending by meat eating status (not controlling for demographic or income differences)

It appears "partial vegetarians" spend more on food than the other two groups, however, when one looks at the demographics this group is also a bit richer, is more likely to have children in the household, and has larger household size - all things that are correlated with higher food expenditures.

After adjusting for differences in demographics, we continue to find differences in spending patterns, though the differences are typically smaller. Here are some graphs I constructed using the estimates in the paper. The figure shows spending for each consumption group assuming each group has demographics equal to the mean demographics in the sample (i.e., each group has the same demographics) for different levels of income.

In general, richer households spend more on food than poor households regardless of whether one eats meat or not. However, at every income level, partial vegetarians spend more than meat eaters while true vegetarians spend less (assuming same gender, household size, etc.). For example, for households earning between $60,000 and $79,000 per year, weekly spending on food for meat eaters is $156, for partial vegetarians its $196, and for true vegetarians its $116.

Here is the same result expressed as a share of income (these are the so-called Engel curves).

Meat eaters in households earning between $60,000 and $79,000 per year spend about 11.6% of their income on food for partial vegetarians at the same income level it's 14.5%, and for true vegetarians it 8.5%.

Of course, these three groups don't have the same incomes. The percent of respondents living in households making more than $100,000/year is 11.3% for meat eaters, 18.3% for partial vegetarians, and 14.4% for true vegetarians. Thus, if one adjusts for differences in household income, some of the differences shown in the above graphs disappear.

Here is a summary of what we found.

“To the extent that self-reported food expenditures are reliably correlated with actual expenditures, true vegetarians spend less money on food than meat eaters and partial vegetarians spend more. Although this result might be used to suggest that meat eaters could replace their meat with vegetables and save around $20 per week in food, this is deceiving. Roughly half of these savings are not due to the change in types of food purchased, but demographic differences. There are certain demographics that one can change in an effort to better mimic true vegetarians. Two of these are body mass index and political attitudes, but although they can be modified by the individual, their impact on food expenditures is small if not zero. The demographic traits that help true vegetarians save money must then reside with more fixed factors like household size, gender, and the like.”