That’s the title of a new working paper I’ve co-authored with Vincenzina Caputo.

Much of research seeking to understand consumers’ preferences for food products and attributes relies on “choice experiments”, which are like simulated shopping scenarios. What makes choice experiments different from a true shopping scenario, however, is that respondents are only asked to choose one product out of a set. In reality, people often choose multiple products from different product categories when shopping, and their preference for one product may depend on what they’ve already put in the shopping basket.

Here’s a brief summary from the paper:

“consumers make multiple food choices at a time and prefer to choose on average 4.4 out of 21 possible foods items. This is especially the case when looking at fresh meat and vegetables. For example, the selection frequency of salad/lettuce increased as respondents selected more items since salad is often used as a side dish. Further, our results reveal that food items act as complements or substitutes. Finally, while in standard [discrete choice experiments] cross-price elasticities are forced to be positive due to single discrete choices, our results also imply negative cross-price elasticities. Overall, these results suggest that the BBCE [basket based choice experiment] is a promising experimental approach that allows for a richer set of substitution and choice patterns as it brings together the advantages of standard [discrete choice experiments] and the advantages of traditional demand system analysis. ”

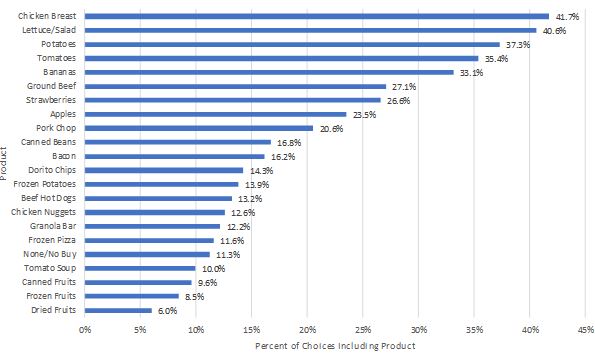

The following figure shows the most common items consumers put in their basket.

Perhaps more interesting, however, are the combinations of items people place in their baskets. For example, given that someone chooses ground beef, the next most common items in the basket are salad/lettuce, potatoes, and then tomatoes. Given that someone has picked ground beef, there is more than a 50% chance each of these vegetables/vegetables also appears in the basket. These sorts of results illustrate the challenge of suggesting people to just increase fruit or vegetable consumption because their values for these items increase when accompanied with meat. For example, one of our model specifications suggests that the value of lettuce/salad increases by more than $4 if it is also accompanied with ground beef.

There’s much more in the paper, which Vincenzina will present at the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association meetings next month.