Throughout this pandemic, there have been many prognostications about the future of eating and proposals to make sure we are better prepared for the future. A common solution that I hear being offered is more direct to consumer, more local, more distributed food supply systems. These ideas have an intuitive appeal and most take it as self evident that these food systems would be more robust and more resilient relative to the status quo. However, I haven’t seen much serious discussion about how these alternative types of food supply chains and systems would have actually performed if faced with the same massive and unexpected shocks witnessed over the past couple months. Buckle in. This is a longish post.

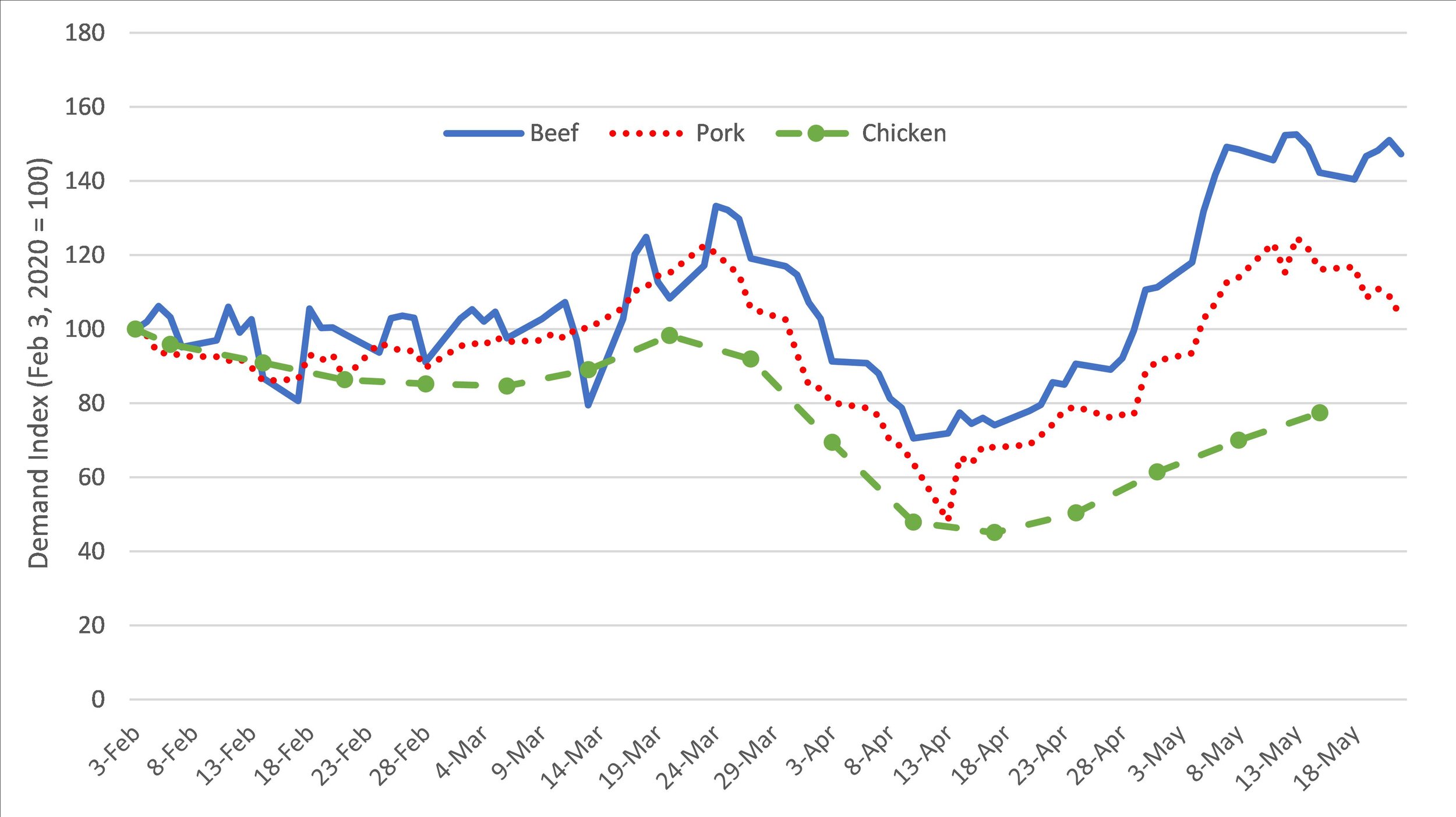

There were two distinct waves and causes to the disruptions in our food sector during the COVID pandemic. The first occurred in mid- to late-March when there was a near shut down in restaurant and food away from home sales and a corresponding spike in demand at grocery stores.

Many of the news stories at the time concerned empty shelves at the grocery store coupled with commodities being dumped or plowed under at the farm. The excess at the farm was primarily a result of the fact that demand for food away from home fell markedly, and the way we deliver food to restaurants is packaged and with machinery that is not easily amenable to delivering food to grocery stores. Moreover, in some cases, there were regulatory barriers that prevented food from moving from the food-away-from home stream to the grocery stream.

A key point here is that the “shock” to the food system was a massive demand shock, with demand destroyed at restaurants along side a big temporary boost in grocery-demand Within a matter of weeks (by early April), the grocery and manufacturing sector had largely work through the massive demand increase and shelves return to near full as groceries sales fell from the near 100% spike to running about 20 to 30% above normal.

What is it about direct to consumer food delivery or farmers markets that would have performed better to these demand shocks? Most of the vegetables that we saw being plowed under were destined for restaurants. Demand at restaurants was destroyed by shutdown orders. This demand destruction would have occurred regardless of whether the supplier to the restaurant was a small and local or whether they were large and distant. The issue wasn’t geographic proximity or scale, rather there was a lack of demand from particular buyers such as restaurants and cafeterias. We seem to notice the farm losses more when it happens on one large farm as opposed to it happening on many small farms.

As indicated, despite the dramatic demand spike, grocery stores were able to quickly work through the disruptions and return to normal within a matter of weeks. Are we really to believe that a supply chain executive for a large supermarket chain would have had an easier and more effective time coordinating with hundreds or thousands of small producers as opposed to a handful of large suppliers? Would smaller manufacturers have been able to ramp up production as quickly in response to the grocery demand spike? Would public health have been better served by many small trucks entering cities to sell produce rather than a smaller number of large semis?

One thing about agricultural production is that it is seasonal. No farmer, whether small or large, local or distant, can immediately, within the time frame of one or two weeks, produce a new crop. The foods we see on our shelves today are a result of agricultural decisions made many months ago and no system, more or less distributed, is going to change that basic biological fact. Crops were destroyed because the demand we anticipated when planting didn’t materialize. Likewise, we don’t have a food replicator for those commodities we tend to buy in grocery stores, it takes time to grow and manufacture them. Thus, the initial challenge with food supply chain was a mismatch of supply and demand brought about by the fact that we cannot immediately respond to demand shocks because there are biological lags associated with agricultural production.

Isn’t the increase in visits to food banks a condemnation of the current food system? In my assessment, this outcome is a result of general economic conditions such as lost income and unemployment NOT a problem with the food system per se. Yes, it would have been nice to get some of the farm surplus to food banks, but someone still needs to pay to harvest, transport, and process it. It isn’t reasonable to expect farmers (local or distant) to incur these costs while they’re also losing significant income. Maybe it’s a role for government to step in and help fill the void, but again, this issue has little to do with the structure of our food supply chain and much more to do with the the overall economic harm people are suffering from lost income.

****

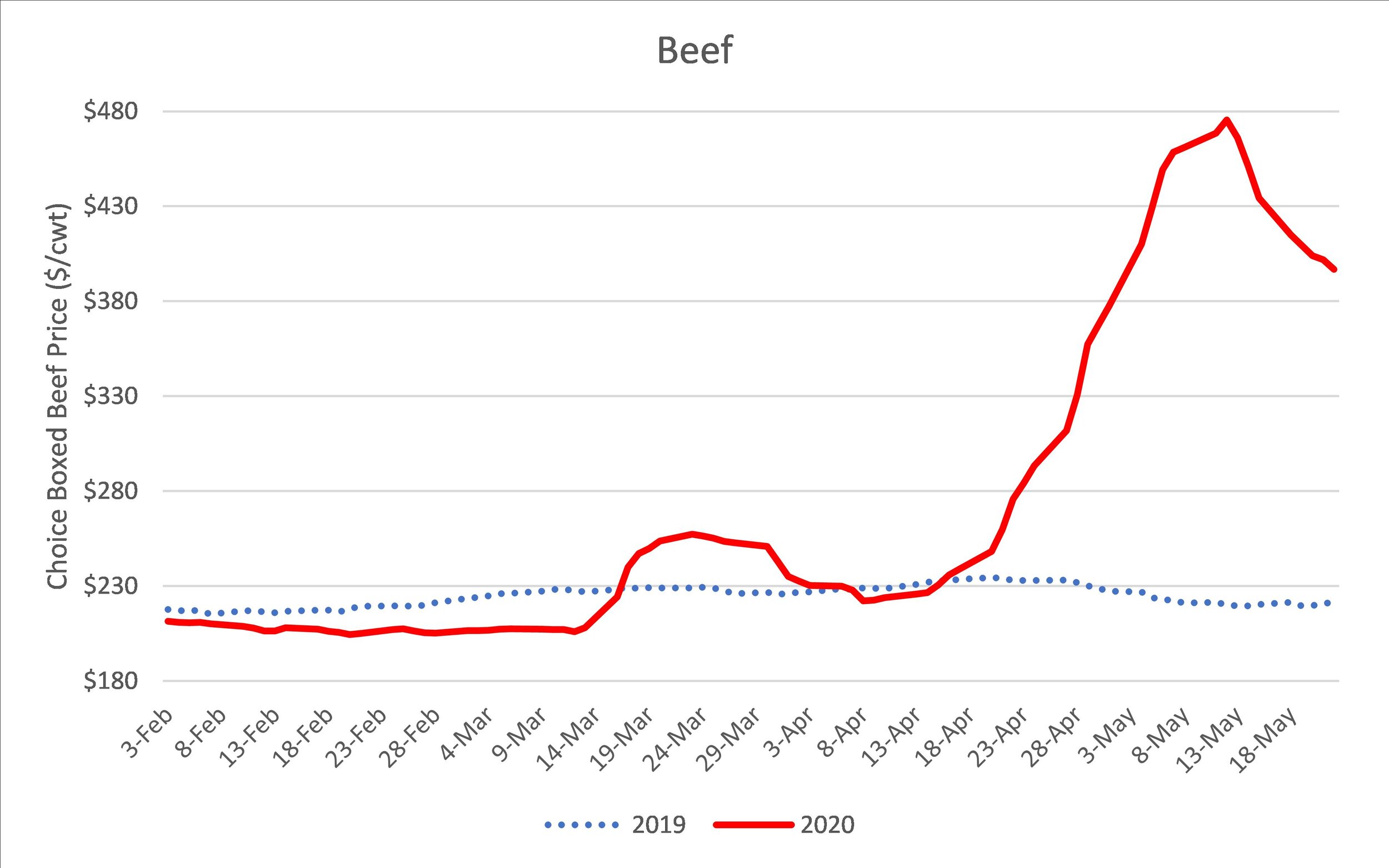

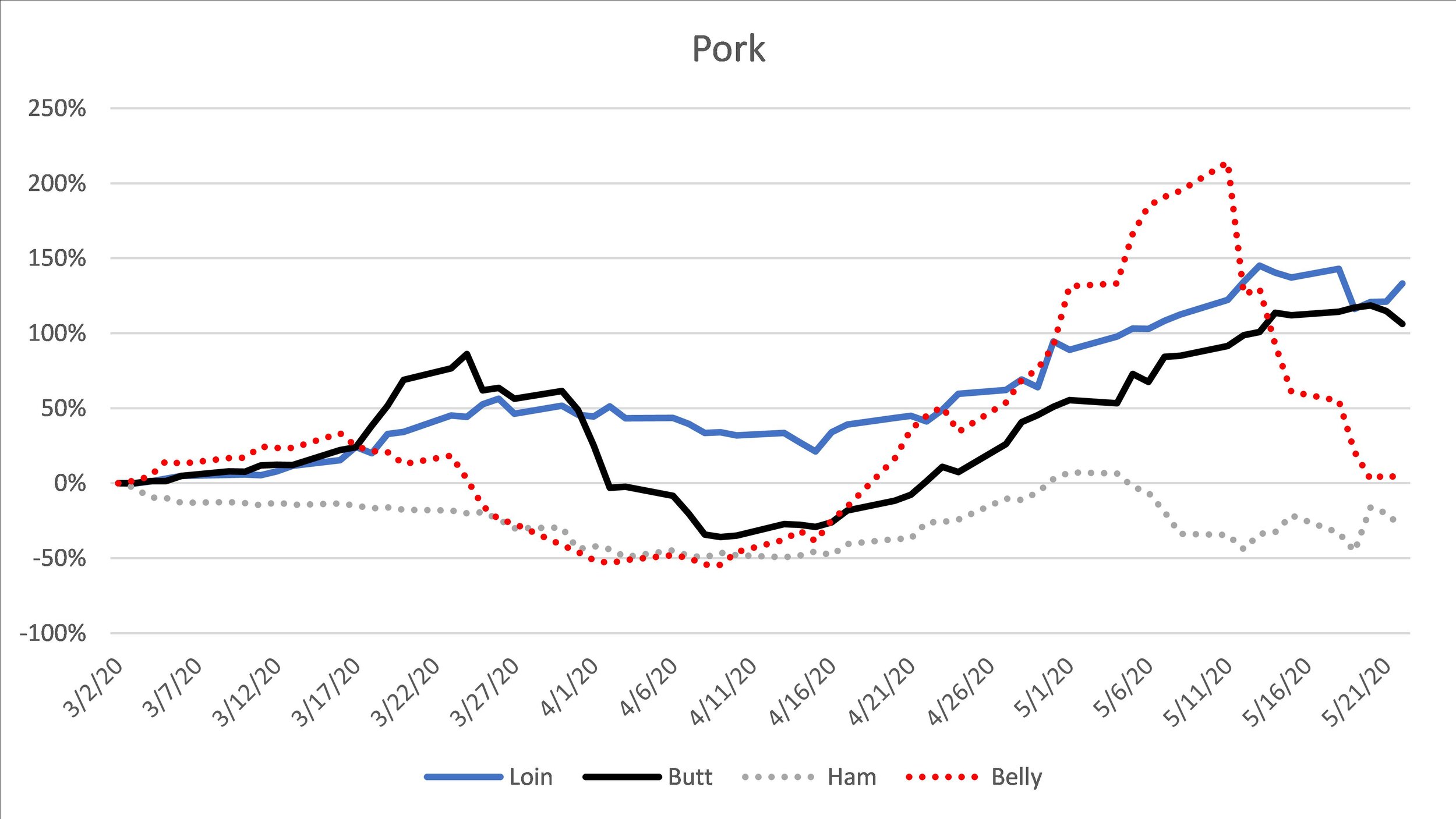

The second major disruption occurred not from a demand shock but rather from a supply shock. In early April, meatpacking plants began closing when workers in the plants contracted COVID19. The meat industry structure is such that there are a small number of very large plants responsible for most of the packing. As such, when any one plant goes down, it’s large enough to have noticeable aggregate impacts in the market.

These observations have lead some folks, including myself, to ask whether a system with a larger number of more medium size plants might not be a more resilient system. One of the reasons COVID19 seems to have heavily affected meat packing is the labor intensive nature of meat packing plants, and the fact that packing plant workers are in a cold, refrigerated environments where air is re-circulated. I appears this environment is particularly conducive to virus spread from worker to worker.

Do we have any evidence that smaller or more medium-size plant wouldn’t have the same sorts of issues with spread of virus from worker-to-worker? All plants, regardless of size, want to control costs. A packing plant requires a large refrigerated building, the cost of which needs to be spread over as many pounds of production as possible. Moreover, when USDA inspectors are required, when there are labs and tests to run, and workers to pay, there is a strong incentive to ensure that a plant can accomplish as much production as possible in as little time as possible. It strikes me that even a more medium sized plant will face the economic incentives to have workers in close proximity (extra square footage in refrigerated atmospheres is very expensive). It’s one reason that I think a more adept solution is automation to reduce reliance on labor.

When we talk about resiliency, somehow people first think of size. But I’m not so sure size is the key in this context; rather, a key characteristic is redundancy. The problem in the current situation is that we have too many animals and not enough room to process them. So, the “fix” is extra capacity in the system.

But, somebody has to pay for that capacity. What we’re essentially asking is for someone to build a multi- million dollar facility and keep it idle for large parts of the week or the year in anticipation of some unexpected future fire, tornado, or pandemic. No company in a competitive environment can withstand the high cost of such idle productive capacity. Even if we could, by government mandate or construction, create new processing plants to create redundant plants in the unlikely event of a fire, tornado, or pandemic, we’d still have to have the ability, in a moment’s instance to ramp up the plant, scale production, hire workers, etc. to pick up the excess from other plants.

There’s also a very strong assumption that there are many communities who want a new packing plant in their backyard. Are there really 100 such communities in the country? Remember the controversy this past fall when Costco wanted to open a new poultry processing plant in rural Nebraska?

Meat packing capacity took a big hit for a couple weeks, but we already appear to be on the rebound (today’s data suggests we are running at about 25% below last year as compared to the 40% reduction we were seeing a week or so ago). Whatever ills result from a small number of very large plants processing most of the livestock in the country, one upside is that we know where the problems are and we have concentrated local, state, local federal efforts (from health authorities to OSHA to USDA) to bring those plants back online as quickly as possible. Would such coordination be as efficient and effective had there instead been hundreds or thousands of small packing plants that were closed down? Again, it strikes me that one of the reasons we’ve focused so much attention on size and scale in meat packing is that it’s so much easier to see when it’s concentrated, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that a more disaggregated system wouldn’t have larger aggregate impacts. That is, we may be suffering from availability bias.

***

None of the above discussion is meant to besmirch local foods or more direct-to-consumer markets. All systems involve costs and trade-offs, including our present supply chain. We can and should try to do better. Let’s also make sure we think hard and ensure efforts to improve will actually achieve the outcomes we want.

****

P.S. I’ve used the word “food system” in this post for ease of exposition but I strongly agree with Rachel Laudan that, “there is not ‘a’ food system but multiple cris-crossing supply chains, some connected, some not.”