There is a general sense that nutritional information on food products is "good" and "valuable." But, just how valuable is it? Are the benefits greater than the costs?

There have been a large number of studies that have attempted to address this question and all have significant shortcomings. Some studies just ask people survey questions about whether they use or look at labels. Other studies have tried to look at how the addition of labels changes purchase behavior - but the focus here is typically limited to only a handful of products. As noted in an important early paper on this topic, by Mario Teisl, Nancy Bockstael, and Alan Levy, nutritional labels don't have to cause people to choose healthier foods to be valuable. Here is one example they give:

“consider the individual who suffers from hypertension, has reduced his sodium intake according to medical advice, and believes his current sodium intake is satisfactory. If this individual were to learn that certain brands of popcorn were low in salt, then he may switch to these brands and allow himself more of some other high sodium food that he enjoys. Better nutritional information will cause changes in demand for products and increases in welfare even though it may not always cause a backwards shift in all risk increasing foods nor even a positive change in health status.”

This is why it is important to consider a large number of foods and food choices when trying to figure out the value of nutritional labels. And that's exactly what we did in a new paper just published in the journal Food Policy. One of my Ph.D. students, Jisung Jo, used some data from an experiment conducted by Laurent Muller and Bernard Ruffieux in France to estimate consumers' demands for 173 different food items in an environment where shoppers made an entire day's worth of food choices. This lets us calculate the value of nutritional information per day (not just per product).

The nutritional information we studied relies on two simple nutritional indices created by French researchers. They are something akin to a NuVal label system or a traffic light system. We first asked people where they thought each of the 173 foods fell on the nutritional indices (and we also asked how tasty or untasty each of the foods were), and then after making a day's worth of (non-hypothetical) food choices, we told them were each food actually fell. Here's a bit more detail.

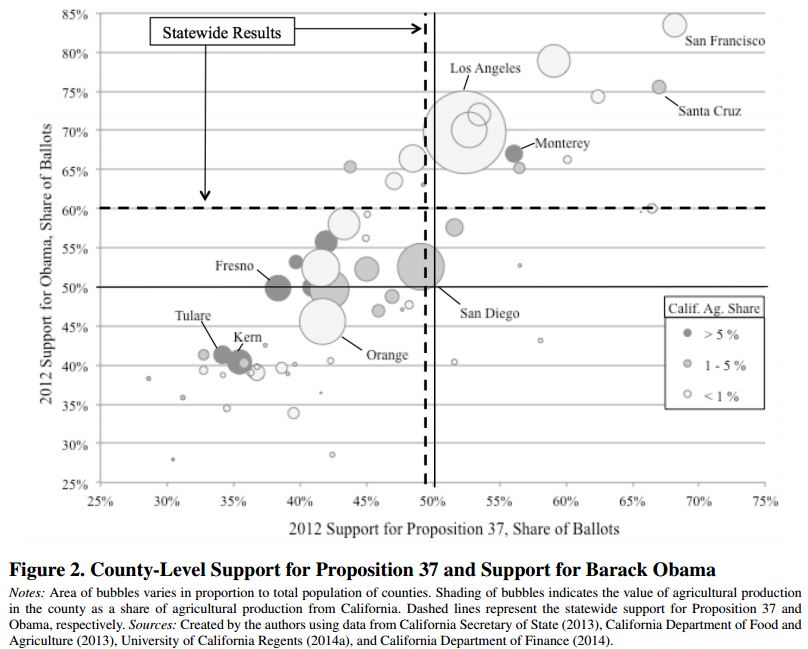

“The initial “day 1” food choices were based on the individuals’ subjective (and implicit) health beliefs. Between days 1 and 2, we sought to measure those subjective health beliefs and also to provide objective information about each of the 173 foods. The beliefs were measured by asking respondents to pick the quadrant in the SAIN (Nutrient Adequacy Score for Individual foods) and LIM (for Limited Nutrient) table (Fig. 2) that best described where they thought each food fit. The SAIN and LIM are nutrient profiling models and indices introduced by the French Food Safety Agency. The SAIN score is a measure of “good” nutrients calculated as an un-weighted arithmetic mean of the percentage adequacy for five positive nutrients: protein, fiber, ascorbic acid, calcium, and iron. The LIM score is a measure of “bad” nutrients calculated as the mean percentage of the maximum recommended values for three nutrients: sodium, added sugar, and saturated fatty acid.2 Since indices help reduce search costs, displaying the information in the form of an index is a way to make the information available in an objective way but also allows consumers to better compare the many alternative products in their choice set.”

Here are the key results:

“In this study, we found that nutrient information conveyed through simple indices influences consumers’ grocery choices. Nutrient information increases willingness-to-pay (WTP) for healthy food and decreases WTP for unhealthy food. The added certainty provided by objective nutrient information increased the marginal WTP for healthy food. Moreover, there is a sort of loss aversion at play in that WTP for healthy vs. neutral food is lower than WTP for neutral vs. unhealthy food, and this loss aversion increases with information. . . . This study estimated the value of the nutrient index information at €0.98/family/day. The advantage of our approach is that the value of information reflects choices over a larger number of possible foods and represents an aggregate value over the whole day.”

I should also note that people valued the taste of their food as well. We found consumers were willing to pay 4.33 eruos/kg more for a one-unit increase in on the -5 to +5 taste scale. To put this number in perspective, let's take a closer look at the average taste rating given to all 173 food items. Most items had a mean rating above zero. The highest rated items on average were items like tomatoes (+4.1), green salad (+4), and zucchini (+3.9). The lowest rated items on average included cheese spread ( 0.2) and Orangina light ( 1.9). [remember: these were French consumers] Moving from one of the lower to higher rated items would induce a four-point change in the taste scale associated with a change in economic value of 4.33 ⁄ 4 = 17.32 euros/kg.