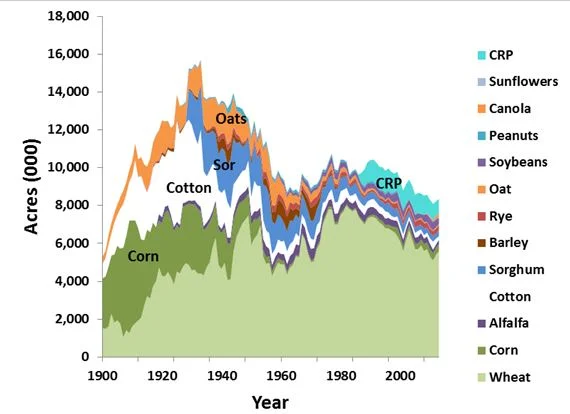

While there was indeed a big plow-up just prior to the dust bowl (which occurred in the 1930s), we can see that we've had just as much land in wheat production in the late 1940s and almost as much in the late 1970s. To the extent that the same is true in other regions and with other crops, it doesn't seem that replanting back to grass is THE explanation (although it might have played some role on more erodible lands in other areas).

A better question.

In the past several years, we've had severe droughts in the great plains similar to the one in the 1930's. Why no repeat of the dust bowl?

Egan asks a similar question, and he points mainly to the aforementioned government policies. He also gives the impression in the end that big corporate agribusinesses have taken over this land (which is largely false; there are fewer farmers today and those farmers are indeed bigger, but they are family farms; moreover his statements on this topic are somewhat ironic given the aforementioned quote that larger farm sizes were needed to avoid poverty). As indicated in the graph above, I don't think the full answer can be that the land has reverted back to idyllic native grasses.

My sense is that it is mainly a result of two factors: better farming technologies/practices and irrigation. To be fair, Egan points to these as potential answers too. Many of the people who moved out to farm the great plains had no prior farming experience. Its no wonder they adopted some practices that were doomed for failure (I'm sure I'd have done the same thing; I'd hate to think what would happen if I were forced to try to make a living at farming today!) Knowledge and experience matter. And sometimes it takes really bad consequences to teach us to do things differently.

On the issue of irrigation, there was an interesting paper (earlier ungated version here) that recently appeared in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics by Richard Hornbeck and Pinar Keskin. They write:

Agriculture on the American Plains has been constrained historically by water scarcity. Post-WWII technologies enabled farmers over the Ogallala aquifer to extract groundwater for large-scale irrigation. Comparing counties over the Ogallala with nearby similar counties, groundwater access increased agricultural land values and initially reduced the impact of droughts. Over time, land use adjusted toward water intensive crops and drought sensitivity increased. Viewed differently, farmers in nearby water-scarce areas maintained lower value drought-resistant practices that fully mitigate naturally higher drought sensitivity. The evolving impact of the Ogallala illustrates the importance of water for agricultural production, but also the large scope for agricultural adaptation to groundwater and drought.

Ultimately, we may never know the ultimate causes and consequences of the dust bowl. It seemed to arise from a unique combination of an adverse turn in weather/climate, poor farming practices, poor economic conditions (the Dust bowl and the Great Depression occurred at the same time - how's that for bad luck!), unscrupulous land salesmen, and bad government policies. The consequences, it seems, were long lasting.

Hornbeck has another 2012 paper (earlier ungated version) specifically on the dust bowl in the American Economic Review related to how long the impacts of the dust bowl were felt. He wrote:

The 1930s American Dust Bowl imposed substantial agricultural costs in more eroded Plains counties, relative to less-eroded Plains counties. From 1930 to 1940,

more-eroded counties experienced large and permanent relative declines in agricultural land values: the per acre value of farmland declined by 30 percent in high erosion counties and declined by 17 percent in medium-erosion counties, relative to changes in low-erosion counties.

and

The Dust Bowl provides a detailed context in which to examine economic adjustment to a permanent change in environmental conditions. The Great Depression may have slowed adjustment by limiting access to capital or outside employment opportunities. Agricultural adjustment continued to be slow, however, through the 1940s and 1950s. Further research on historical shocks may help understand what conditions facilitate long-run economic adjustment. The experience of the American Dust Bowl highlights that agricultural costs from environmental destruction need not be mitigated mostly by agricultural adjustments, and that economic adjustment may require a substantial relative decline in population.