A good passage by Keith Kloor on the subtle shift by some in the "food movement" on GMOs:

As I have said to Lynas, this kind of turnabout owes not so much to discovering science but more to unshackling oneself from a fixed ideological and political mindset. You can’t discover science–or honestly assess it–until you are open to it. The problem for celebrity food writers like Bittman and Michael Pollan, who is also struggling to reconcile the actual science on biotechnology with his worldview, is that their personal brands are closely identified with a food movement that has gone off the rails on GMOs. The labeling campaign is driven by manufactured fear of genetically modified foods, a fear that both Pollan and Bittman and like-minded allies have enabled.

Kloor argues that

Now that this train has left the station, there is no calling it back, as Bittman seems to be suggesting in his NYT column.

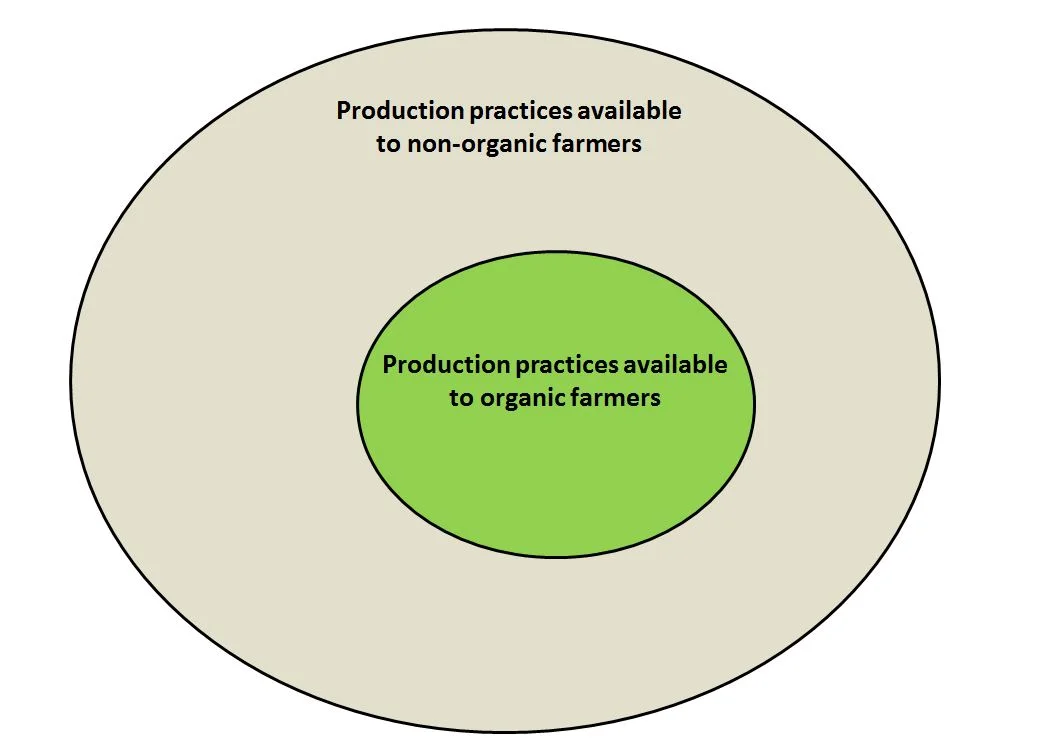

There may be no calling it back but I suppose we should at least celebrate the fact that celebrity foodies aren't actively at the engine anymore. Now if I can just persuade Bittman and Pollan on the science and economics that conflict with some of their other pet food causes (including some of the nonsense Bittman spread about organics in the same column where he admits the safety of GMOs) . . .