On a recent flight, I listened to the latest Freakonomics podcast in which Stephen Dubner interviewed the University of Chicago economist Steven Levitt about some of his latest research. The podcast is mainly about how Levitt creatively estimated demand for Uber and then used the demand estimates to calculate the benefits we consumers derive from the new ride sharing service.

Levitt made some pretty strong statements at the beginning of the podcast that I just couldn't let slide. He said the following:

“And I looked around, and I realized that nobody ever had really actually estimated a demand curve. Obviously, we know what they are. We know how to put them on a board, but I literally could not find a good example where we could put it in a box in our textbook to say, “This is what a demand curve really looks like in the real world,” because someone went out and found it.”

As someone whose spent the better part of his professional career estimating consumer demand curves, I was a bit surprised to hear Levitt claim "nobody ever had really estimated a demand curve." He also said, "we completely and totally understand what a demand curve is, but we’ve never seen one." The implication seems to be that Levitt is the first economist to produce a real world estimate of a demand curve. That's sheer baloney.

The most recent Nobel prize winner in economics, Angus Deaton, is perhaps most well known for his work on estimating consumer demand curves.

In fact, agricultural economists were among the first people to estimate real world demand curves (see this historical account I coauthored a few years ago). Here is a screenshot of a figure out of a paper by Schultz in the Journal of Farm Economics in 1924 who estimated demand for beef. Yes - in 1924! I'm pretty sure that figure was hand drawn!

Or, here's Working in a paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 1925 estimating demand for potatoes.

Two years later in 1927, Working's brother was perhaps the first to discuss "endogeneity" in demand (how do we know we're observing a demand curve and not a supply curve?), an insight that had a big influence on future empirical work.

Fast forward to today and there are literally thousands of studies that have estimated consumer demand curves. The USDA ERS even has a database which, in their words, "contains a collection of demand elasticities-expenditure, income, own price, and cross price-for a range of commodities and food products for over 100 countries."

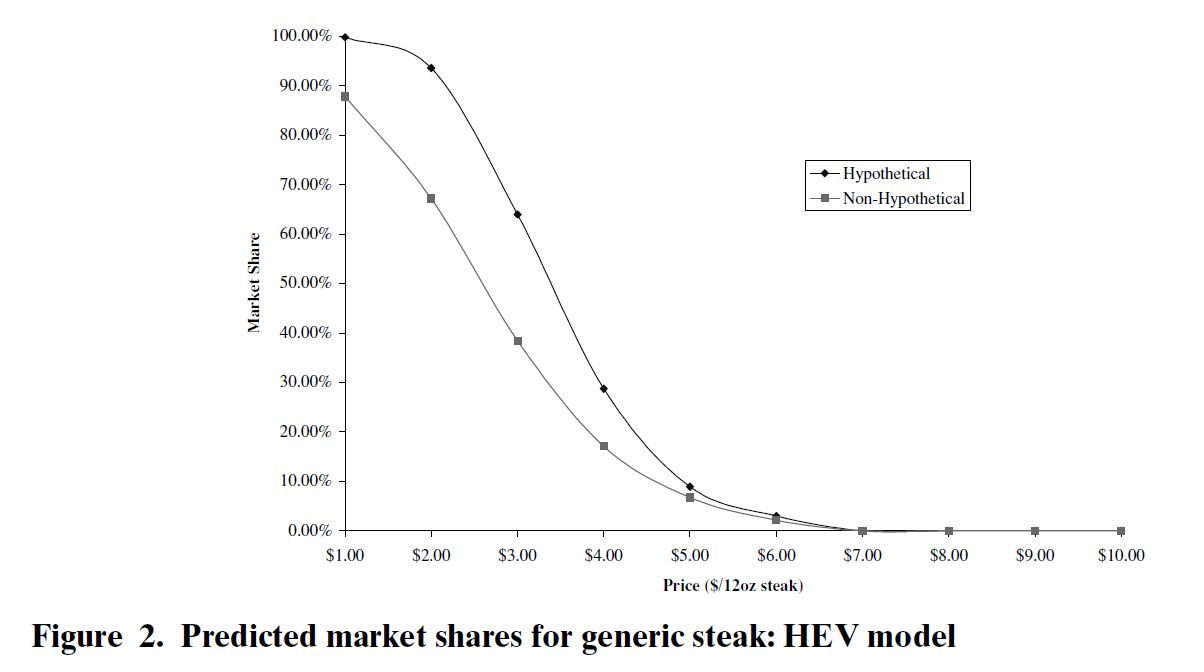

Here is a figure from one of my papers, where the demand curve is cleanly identified because we experimentally varied prices.

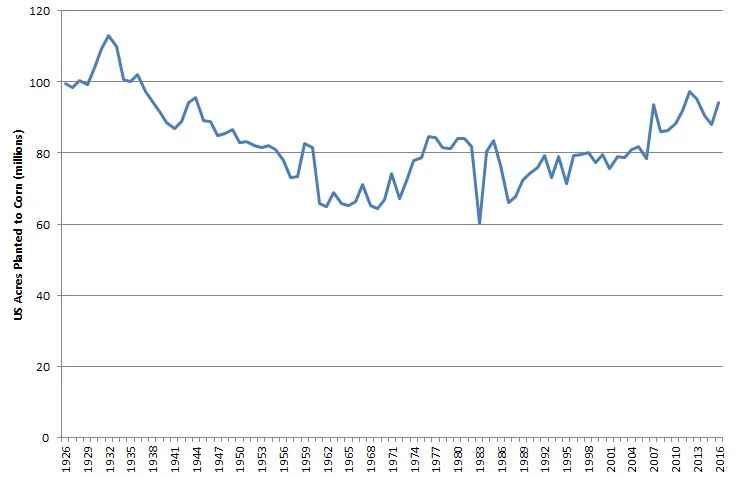

And, of course, I've been doing a survey every month for over three years where we estimate demand curves for various food items.

In summary, I haven't the slightest idea what Levitt is talking about.