This article in the New York Times by Stephanie Strom argues that something may be fishy with chicken prices.

The main focus of the article is about a widely used price index of chicken prices (the so-called Georgia Dock index) that is used by some retailers to negotiate prices with poultry producers. Apparently the Georgia Dock price of chicken is higher than a couple of other price indices of wholesale chicken prices (one of which the USDA just created), and the Georgia Dock price hasn't fallen by as much as another index in recent months. The article insinuates that something nefarious could be going on to artificially inflate the Georgia Dock price (and by extension the retail prices you and I pay for chicken).

I have no deep insights into the allegations in the article. However, I do want to push back just a bit on the broader issue of chicken prices relative to beef and pork. Here is Strom:

“Beef prices at grocery stores are lower. So, too, are pork prices. But chicken? Steady as she goes.

A glut of corn and soybeans has led to lower prices for a variety of meats. But chicken in grocery stores has bucked the trend, leaving prices up for shoppers and buoying the fortunes of major chicken producers.”

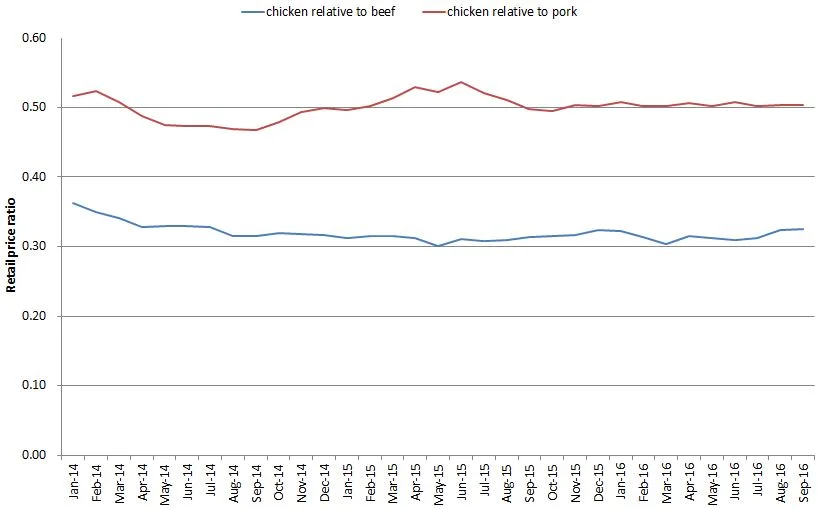

I'm not so sure about that first line - that beef and pork have become cheaper relative to chicken. Using data from the USDA-ERS on retail meat prices, I constructed the following graph showing the retail price of chicken relative to the retail prices of beef and pork. Unfortunately, the last data point is September (the USDA bases it's calculations on retail prices reported by Bureau of Labor Statistics, but BLS hasn't released October prices yet), so it is possible that there have been some changes in recent weeks that aren't reflected in the graph below (but, even still, one might wonder why it's just now in the past month or two that the poultry producers figured out how to rig the wholesale price).

Two broad points:

1) As of September, the ratio of chicken to pork prices is essentially flat (i.e., chicken isn't getting more expensive relative to pork). While chicken is a tad more expensive than beef in August and September relative to July, overall the trend looks pretty flat to me.

2) Chicken is really cheap! It is about half the price of pork and about a third the price of beef.

Moreover, if we take a step back and take the long view, chicken has progressively gotten cheaper relative to beef. (note: the graph below uses the price for a whole chicken rather than composite retail prices as in the prior graph because the whole chicken data series goes back further in time). Whereas whole chickens sold about 40% the price of beef in the 1970's, today they're about 25% the price of beef.

So, are poultry producers manipulating a price index leading us to pay more than we otherwise would have paid for chicken? I don't know. But, as the above graph shows, there's a whole lot of other things poultry producers have done over time (better genetics, better feed, better housing, etc.) to make chicken ever more affordably priced compared to other proteins.