The journal Agribusiness just released a new paper I co-authored with Clint Neill and Rodney Holcomb. The work was motivated by the observation that every state in the U.S. has an agricultural marketing program aimed at promoting foods from their state. Examples include the “Taste NY” and “Pride of New York” programs as well as “Go Texan” and “California Grown.”

Our questions were two fold: 1) How much do consumers value products labeled with their state’s logo relative to other states’ products, and 2) what are the implications for state marketing programs?

We surveyed 6,900 consumers in an eight‐state contiguous region. For our application, we chose milk, and asked people which of several milk products with different state logos (and a regional or national brand) they preferred at different prices.

Not surprisingly, we find that consumers prefer products with their own state’s logo. For example, Texans’ average willingness-to-pay (WTP) for Texas milk is $4.14/gallon, but Texans’ value for milk from bordering states, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Arkansas only averaged $1.82, $2.65, and $2.72/gallon, respectively. There are a number of interesting patterns. Here’s an excerpt from the text:

“While each state’s consumers tend to prefer their own label and have a distinct order of preference for other states, the asymmetry between states is less clear. For example, Oklahoma consumers are willing to pay $2.84 for the Texas label but Texas consumers are only willing to pay $2.65 for the Oklahoma label, so there is an asymmetry of $2.84−$2.65 = $0.19. Thus, Oklahomans value the Texas label $0.19 more than Texans value the Oklahoma label.

Table 5 shows this type of asymmetry for all combinations. Interestingly, every other state’s consumers value the Colorado label more than Colorado consumers value other states’ labels. Alternatively, New Mexico consumers value all other state brands more than the other states’ consumers value the New Mexico label.”

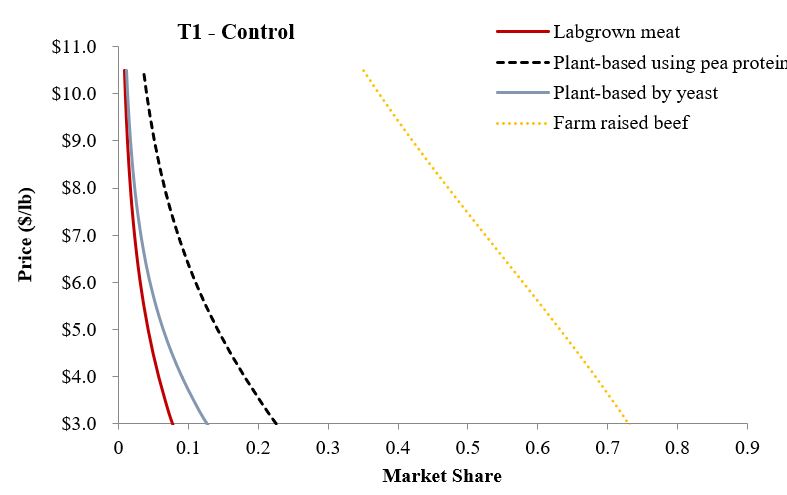

While it is perhaps obvious that people in a state will tend to prefer their own products, it is also important to note that people have some value from agricultural products from other states (and, in fact, some small share of people prefer products from another state). The result is that state branding programs “steal” consumers from other states (the effect is a bit like the prisoner’s dilemma problem). The state branding program looks great if your the only state that has the program, but if all states have their own programs, the effects partially serve to cancel each other out. Here’s what we write about this so-called “beggar thy neighbor” effects:

“In the case of market shares, we were able to illustrate the large decreases as a group of producers from one state starts with having no state branded competitors to competing against several other brands within a region. Producers, ideally, would have a higher return if they were the only ones with a state label, but the optimal strategy for all agents in the region is to utilize a state label. Thus, the potential beggar‐thy‐neighbor scenario is possibly a Nash equilibrium. Furthermore, states who market their brand outside their borders are shown to have increased total market share”

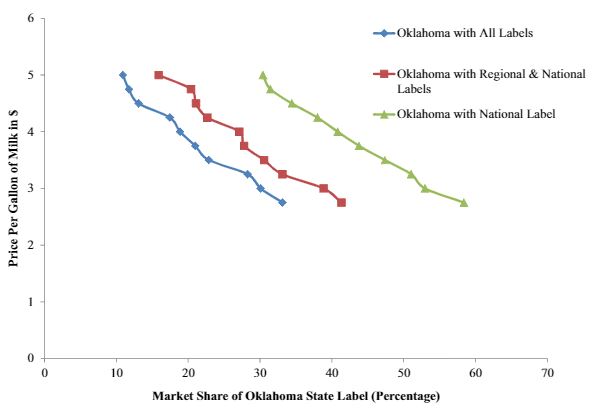

For example, below is a graph showing what happens to demand for milk with a “Made in Oklahoma” label when no other states label their product (the green line with triangle markers) relative to what happens to demand for “Make in Oklahoma” milk when other states introduce their own labels (the red and blue lines). As the figure below shows, the market share more than halves when one state’s label has to compete with all the others in a region.

One potential solution (at least from the producer’s perspective) we discuss is for groups of states to band together and use a regional label.