Rather, than going line-by-line through the report, I think it’s useful to take a step back and see this report as another front in what seems to be an escalating war on meat and animal food products (recall the debate surrounding the scientific advisory report on dietary guidelines back in 2015? Here were my thoughts then). What I thought I’d do in response is to provide some broader thoughts about some of the debates that have arisen about meat consumption. My purpose isn’t to defend meat and livestock industries, but to help explain the consumption patterns we see, add some important context and nuance to these discussions, and help ensure consumer welfare isn’t unduly harmed. (Full disclosure: over the years, I’ve done various consulting projects for meat and livestock groups such as the Cattlemen’s Beef Board, the Pork Board, and the North American Meat Institute. All of this work was on specific projects or data analysis related to labels or demand projections, and none of these groups support writing such as this, but I mention it here for sake of transparency).

Here are my thoughts.

These debates can be contentious because meat, dairy, and egg production is big business and critically important to the economic health of the agricultural sector. For example, these USDA data show in 2017 in the U.S. the value of cattle/calves was about $67 billion, poultry and eggs about $43 billion, diary about $38 billion, and hogs about $21 billion, for a total of $176 billion at the farm gate. Contrast this with the value of corn ($46.6 billion), vegetables and melons ($19.7 billion), fruits and nuts ($31 billion), or wheat ($8.7 billion). In many ways, livestock/poultry can be see as “value added” production because these animal products rely on corn, soy, hay, and grass

Given the farm-level statistics, it shouldn’t be surprising to learn that consumers spend a lot on meat, dairy, and eggs. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey suggest that in 2017 consumers spend about $181 billion on animal products eaten at home. This doesn’t count food away from home, which is 43.5% of food spending according to these data (spending on food away from home isn’t segregated into food types as is food at home). Of total spending on food at home, 32% goes toward meat, dairy, and eggs.

If anything, data suggest demand for meat (i.e., the amount consumers are willing to pay for a given quantity of meat) has been steady or rising over the past decade. For example, see these demand indices created by Glynn Tonsor. His data also shows there has been a steady increase in demand for poultry for the past several decades. At the same time, my FooDS data suggests a slight increase in the share of people who report being vegetarian or vegan over the past five years - going from around 4% in 2013 to around 6% in 2018. So, aggregate demand for animal products is up, although there seems to be increasing polarization on both ends of spectrum. We also find that meat consumption is increasingly related to political ideology, with conservatives having higher beef demand than liberals.

There are important demographic differences in meat consumption, but the results highly depend on which meat cuts we are talking about. For example lower income households have higher demand for ground beef and lower demand for steak than higher income households. Broadly speaking, meat consumption is a “normal good”, which means that consumption increase as incomes rise. This is particularly true in developing countries. One of the first things people in developing countries add to their diet when they get a little more money in their pockets is animal protein.

Given the high levels of aggregate meat consumption indicated above, the evidence suggests strong consumer preferences for meat and animal-based products. Taxes on such products will harm consumer welfare, and will be costly if, for no other reason, because of the size of the industry. Stated differently, consumers highly valuing having animal protein in their diets. This study shows the average U.S. consumer places a higher value on having meat in his or her diet than having any other food group.

Calls for taxes are often predicated on the notion that there are externalities from meat, egg, and dairy production that need to be internalized (otherwise, this would amount to little more than “nannying” or paternalism). The externalities on the health care front presumably come from the fact that we have Medicare and Medicaid, which socialize health care costs. As I’ve written about on many occasions (e.g., see this paper), these “externalities” do NOT create economic inefficiencies because they simply represent transfers from healthy to the sick. Any inefficiencies that arise occur because of moral hazard (i.e., people eating unhealthy because they think the government/taxpayers will foot the bill), and the solution to this insurance problem is typically to require deductibles or risk-adjusted insurance pricing, which nobody seems to be proposing as a solution. As for environmental externalities, the key is to ensure prices for inputs such as water or energy, or outputs such as carbon or methane, reflect external costs. In this sense it isn’t the cow or chicken that is the “sin” but the under-priced water or carbon. Here the goal is to adopt broad policies that apply to all sectors (ag and non-ag) and that encourage and allow for innovation to reduce impacts.

On climate impacts of animal agriculture, it is important not to confuse global figures of climate impacts with U.S. figures, which tend to be much lower (e.g., see my piece in the WSJ a few years ago on this topic). Why would climate impacts be lower in the U.S.? Because we tend to be more intensified and productive than elsewhere in the world. I know it sounds counter-intuitive, but more intensive livestock operations (because of the massive productivity gains) can significantly reduce environmental impacts when measured on a per unit of output (e.g., pound of meat or egg) basis.

As for carbon impacts, the big culprit here is beef and to a lesser extent (due to the smaller cattle numbers), dairy. Why? Because cattle are ruminants. The great benefit of ruminants is that they can take foodstuffs inedible to humans (e.g., grass, hay, cottonseed) and convert them into products we like to eat (e.g., cheese, steak) (see further discussion on this here). The downside is that ruminants create methane, which is a potent greenhouse gas (GHG). The good news is that the GHG emissions from beef production have significantly fallen over time because of dramatic productivity gains (see this paper), but they’re not zero. It’s also important to note that not all greenhouse gasses are created equal, and while methane is a potent greenhouse gas, my understanding is that the impacts from livestock are less persistent in the atmosphere than are other types of greenhouse has emissions. While we can cut GHG emissions by eating less beef, at least in the U.S., the impacts are fairly small (the EPA puts contributions from livestock at around 3-4% of the total), we can also make strides by continuing to increase livestock productivity.

While cattle are more problematic on the GHG front, it is important to note that there are likely tradeoffs (real or perceived) on the animal welfare front in comparison with other species. Most beef cattle live most of their lives outdoors on a diet of grass or hay. Cattle often make use of marginal lands that would be environmentally degrading to bring into row crop production. By contrast, most pork and poultry live the vast majority of their lives indoors on a diet of corn and soy. See my book with Bailey Norwood on the topic of animal welfare.

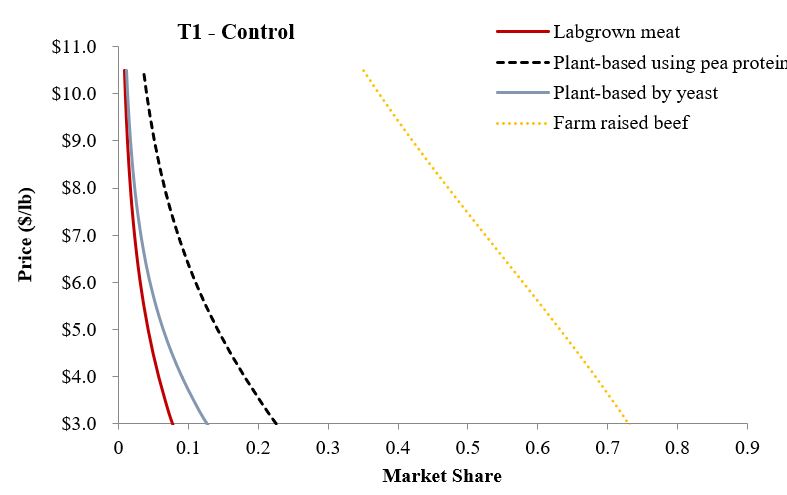

There are some interesting innovations happening on the “lab grown meat” and “plant-based protein” space, which aim to replace protein from animal based sources. I haven’t seen these innovators make many claims about relative health benefits, but they often suggest significant benefits in terms of environmental impacts. I hope they’re ultimately right, but they’ve got a long way to go. Lab-grown meat isn’t a free lunch, and all those cells have to eat something. As I’ve also noted elsewhere, it is curious that these products (plant- or cell- based) are still more expensive than conventional meat products. If these alternative proteins are really saving resources, they should ultimately be much less expensive. Time will tell.

Despite the excitement around the alternative protein sources, I don’t think we’ll see an end to cattle production anytime in the near future. Why? Well, there is the aforementioned marginal land issue; many agricultural lands aren’t very productive for use in other activities other than feeding cattle or housing other livestock or poultry. Another issue is that cattle and other livestock are food waste preventing machines. A big example here is distillers grains. What happens to all the “spent” grain that runs through ethanol plants or beer breweries? Its feed to livestock. The same is true of “ugly fruit”, non-confirming bakery items, and more. Also, without animal agriculture, where will organic agriculture get all it’s fertilizer, which currently comes from the manure of conventionally raised farm animals?

Back to the EAT-Lancet commission, one of the big arguments for reducing meat consumption is health. While there are many studies associating meat consumption with various health problems, the strength of evidence is fairly weak. One big problem is that it’s really tough to do dietary-impact studies well and a lot of the evidence comes from fairly dubious dietary recall studies, but the other issue is that there is generally little attempt to separate correlation from causation. As I’ve written in other contexts, “Its high time for a credibility revolution in nutrition and epidemiology.”

The EAT-Lancet report focuses both on health and sustainability issues. However, as I noted with regard to the 2015 dietary guidelines, which initially aimed to do the same, this conflates science and values. As I wrote then, “Tell us which foods are more nutritious. Tell us which foods are more environmentally friendly. But, don't presume to know how much one values taste vs. nutrition, or environment vs. nutrition, or price vs. environment. And, recognize that we can't have it all. Life is full of trade-offs.”

Finally, I’ve heard it suggested that we need new policies and regulations to offset bad farm policies, which have led to overproduction of grains and livestock. This view is widely believed and also widely discredited. For example, see this piece by Tamar Haspel in the Washington Post. In the U.S., beef, pork, broilers, and eggs receive no direct production subsidies. Yes, there are various subsidies for feedstocks like corn and soy, but there are also other policies that push the prices of these commodities up rather than down (why would farmers want policies that would dampen the prices of their outputs?). Large scale CAFOs (confined animal feeding operations) must comply with a host of rules and regulations that raise costs (it should be noted that the government provides some funding, through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) program, to incentivize certain practices by CAFOs thought to improve environmental outcomes). If U.S. farm bill was completely eliminated, there would not doubt be some change, but it wouldn’t do much to change the volume of meat, dairy, and egg produced.

That’s more than enough to chew on for now.