The other day, I was asked whether I thought the price of organic foods would fall as the market share for organic increased. The answer is: it depends. If increases in consumer demand outpace supply, prices will rise. By contrast, if supply increases at a faster rate than consumers' willingness-to-pay for organic, prices will fall. I suspect that as Wal-Mart and other large retailers become bigger players in the organic market, it will bring about some cost efficiencies that are likely to lead to a reduction in organic price.

That said, organic will never be as inexpensive as non-organic (generally speaking, as I'm sure it might be possible for a particular crop in a particular location in a particular year to experience a price inversion).

Statements such as this normally invoke a debate about whether organic yields and costs are higher/lower than conventional yields and costs. For example, the following was written after a Twitter conversation on the subject

Again, the available data offers conflicting results: there’s evidence that organic yields can match conventional yields over the long-term, especially in less-than-ideal conditions. Other studies point to lower organic yields, especially in crops with high fertility requirements. The primary challenge in extrapolating these results to a “feeding the world” scenario is the issue of context.

Invariably, the evidence given in support of the argument that organic yields can surpass conventional yields is taken from organizations like the Leopold Institute (the paper referenced in the above quote was a proceedings paper, not one that went through the typical submission process) or the Rodale Institute that advocate on behalf of organic. That's why it is instructive to turn to larger scale literature reviews, like this one in the journal Agricultural Systems summarizing 362 studies, which shows that organic yields are 80% of conventional on average. Or turn to the top science journals, like Nature, where a recent paper showed that organic yields are typically 25% lower than non-organic. (note: these review studies show a lot of variability in the organic-conventional yield gap; sometimes the gap is large and sometimes is is almost non-existent).

The quality and quantity of the evidence quite clearly points to the fact that organic yields tend to be lower than non-organic. Yet, it seems, this never actually convinces anyone who believes the opposite. Thus, rather than a show-me-your-study-and-I'll-show-you-mine discussion, sometimes it is useful to make a conceptual argument.

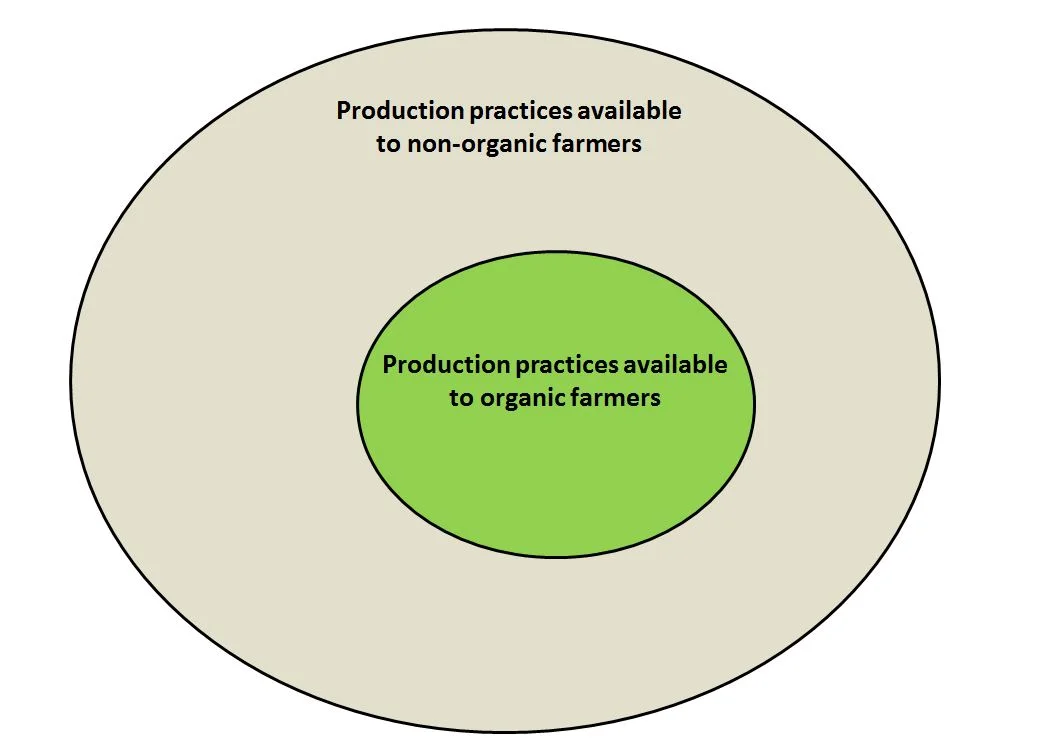

The reason I would never expect organic yields to typically surpass non-organic is summarized in the following figure.

Here is the basic point conveyed in the picture above: a non-organic farmer is free to use any of the practices available to an organic farmer (e.g., no-till or low-till farming, cover crops, etc) but an organic farmer can only use some of the practices that are available to a non-organic farmer. Thus, the range of possible production practices, costs, and outcomes for organic must be a sub-set of that of non-organic.

Being an organic farmer implies following a set of rules defined by the USDA. These rules restrict the practices available to an organic farmer relative to a non-organic farmer. Organic farmers cannot use "synthetic" fertilizer, Roundup, biotechnology, atrazine, certain tillage practices, etc., etc. It is a basic fact of mathematical programming that adding constraints never leads to a higher optimum.

I suspect I know what an organic advocate will next argue: well in the long-run organic soils will build up nutrients and organic matter and will eventually achieve higher yields than non-organic. That may be (or may not be) true, but that does nothing to nullify my point. If it turns out that, say, 10 years down the road, organic farmers begin routinely experiencing higher yields, then non-organic farmers can copy those practices (assuming they're not higher cost) and again match organic yields, and eventually surpass them - because - yet again- they will have options available to them that organic farmers don't. Like biotech. Like ammonium nitrate.

Now, maybe organic better reduces environmental or human health externalities. I'm not particularly persuaded by the evidence on that front, but that is a reasonable debate worth having. But, arguing that organic yields can (generally) exceed non-organic yields is not supported by the best empirical evidence or by logic.