We observed a noticeable uptick in consumer awareness of Salmonella in the news this month - likely a result of widely publicized Salmonella outbreaks. Interestingly, however, concern for Salmonella did not increase this month compared to last. Concern for GMOs was down a bit this month.

Several new ad hoc questions were added to the survey this month.

One set of questions related to food waste. These will be reported separately at a later date.

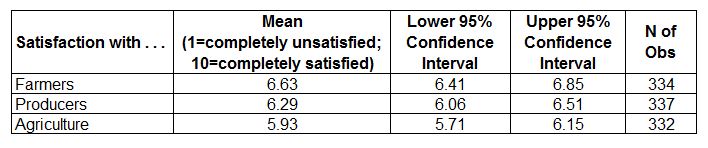

Another set of questions dealt with consumers’ satisfaction with farmers and agriculture, and the survey was designed to see how the framing affected satisfaction. The questions came about after a conversation with Mary Ahearn at USDA-ERS.

Respondents were randomly allocated to one of three conditions. In the 1st condition, participants were asked: “How satisfied are you with the decisions and manage practices of farmers these days?" Respondents in the 2nd condition were asked the same question but the words “of farmers” were replaced with “of agricultural producers”. Respondents randomly allocated to the 3rd condition were asked the same question but the words “of farmers” were replaced with “in agriculture”.

All responses were on a 1 to 10 slider scale where 1 was “completely dissatisfied” and 10 was “completely satisfied.”

Overall, respondents were more satisfied than dissatisfied with farmers, producers, and agriculture, with means higher than 5 our of 10 for all three. However, respondents were affected by framing. On average (on the 1 to 10 scale), there was greater satisfaction with “farmers” at 6.63 than for “producers” at 6.29 and than for “agriculture” at 5.93.