I thoroughly enjoyed reading this paper by Rebecca Taylor and Sofia Villas-Boas, which was just published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics. The research makes use of a new data set - the National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey (FoodAPS) - initiated by the USDA to study where people of different income levels prefer to shop for food. This question is relevant to the debate on so-called food deserts. Are poorer households eating less healthily because of the lack of "good" food outlets in their area, or are there no "good" food outlets in an area because people there don't want that kind of food? To sort this out, you need to know where people of different incomes prefer to shop, and that's precisely what Taylor and Villas-Boas estimate.

Their data suggest that, if anything, lower income households tend to have more stores near them, and at least one store closer to them, than higher income households. For example, in a 1 mile radius, low income households have, on average, 1 superstore near them, whereas higher income households have, on average, only 0.58. Using the USDA's definition of a food desert, the authors calculate that only 5%, 8%, and 3% of low, medium, and high income households live in a so-called food desert. Whereas low income households live, on average, closer to the nearest farmers market than high income households (10.7 miles vs 11.93 miles), high income households are more likely to actually visit a farmers market.

The authors go on to estimate a consumer demand model. Where do consumers prefer to shop given the distances they have to travel? When economists say "prefer" - they don't mean how one feels about a location or the images it conjures up, but rather what is actually chosen. The authors find that people prefer going to locations that are closer to home. That is, people don't like to travel too far to shop. This estimate, then, lets them calculate how far one is willing to travel to shop at one type of store vs. another. The authors consider 9 types of stores (including restaurants and fast food outlets), and find farmers markets are the least preferable shopping outlet in that people are willing to travel the least distance to get to a farmers market.

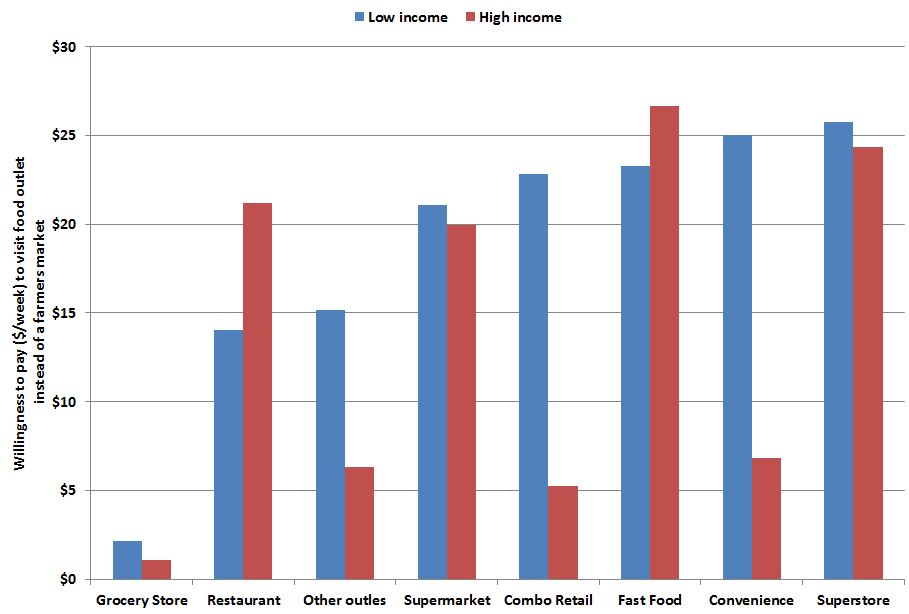

Using the authors estimates, I calculated how much people would be willing to pay ($/week) to shop at each of the 8 other types of food outlets instead of the (least preferable) farmers market.