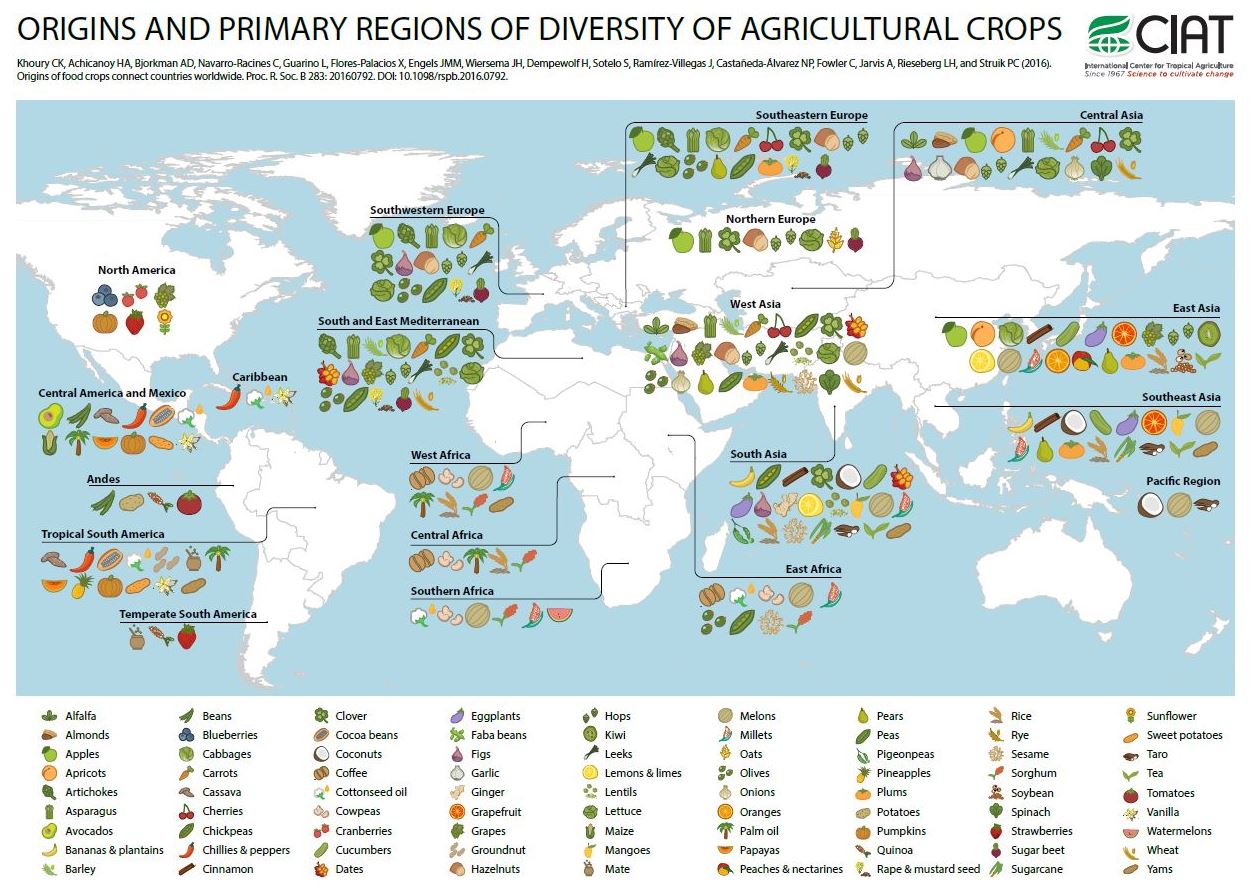

I've seen a number of stories on the research of a team of people at International Center for Tropical Agriculture, the USDA, and elsewhere, some of which was published in a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B and in another paper in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science (PNAS). The team aimed to identified where many of our crops originated and how our eating patterns have changed over time.

Their website has a number of fantastic, interactive visualizations. Here's one.

What I like about the figure above is how it challenges our idea of what is "local" or "authentic." It also illustrates how much we've gained from trading with people in different parts of the world.

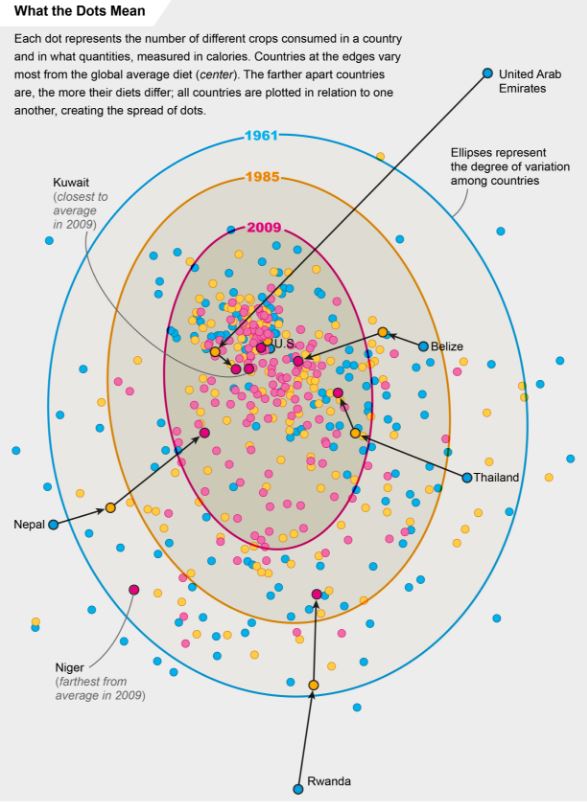

The folks at Scientific American put together this graph based on data in the PNAS article, showing the convergence of dietary patterns worldwide.

While there might be a temptation to decry the "sameness" brought about by globalism and the loss of cultural foods, the reality is much cheerier. First, as the initial figure showed, what we think of as "our" cultural foods are probably relatively recent historical constructs. Second, one of the reasons people eat more similarly to each other across the world is that we are now all eating each other's foodstuffs. We've taken the best from each country and culture and exported it everywhere, and as a result have more diverse diets. Finally, this trade has forestalled the doom-and-gloom Malthusian concern, as there has been a near universal increase in calorie availability worldwide.

Here's from the abstract of the PNAS article.

“We assess trends over the past 50 y in the richness, abundance, and composition of crop species in national food supplies worldwide. Over this period, national per capita food supplies expanded in total quantities of food calories, protein, fat, and weight, with increased proportions of those quantities sourcing from energy-dense foods. At the same time the

number of measured crop commodities contributing to national food supplies increased, the relative contribution of these commodities within these supplies became more even, and the dominance of the most significant commodities decreased. As a consequence, national food supplies worldwide became more similar in composition, correlated particularly with an increased supply of a number of globally important cereal and oil crops, and a decline of other cereal, oil, and starchy root species. The increase in homogeneity worldwide portends the establishment of a global standard food supply, which is relatively species-rich in regard to measured crops at the national level, but species-poor globally. These changes in food supplies heighten interdependence among countries in regard to availability and access to these food sources and the genetic resources supporting their production, and give further urgency to nutrition development priorities aimed at bolstering food security”