The USA Today ran a story about meat shortages and exports in which I was quoted. There are several crisscrossing narratives running through the piece, so I thought it might be useful to clarify a few points.

On the one hand, the article discusses the volume of meat US packers exported to other countries, with the presumption being that it’s wrong to export meat abroad when we have shortages at home. But, then the article also argues:

“But Americans were never at risk of a severe meat shortage, a USA TODAY investigation found, based on an analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture data and interviews with meat industry analysts.”

If that’s true, then the argument about exports seems irrelevant.

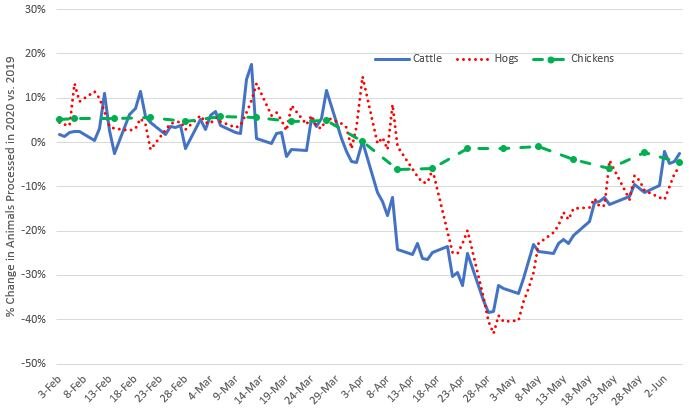

In any event, were we at risk of shortages? It is clear the packing sector took a significant, unprecedented hit and was producing far less beef and pork compared to last year. Here’s a figure I created based on USDA data on processing volumes.

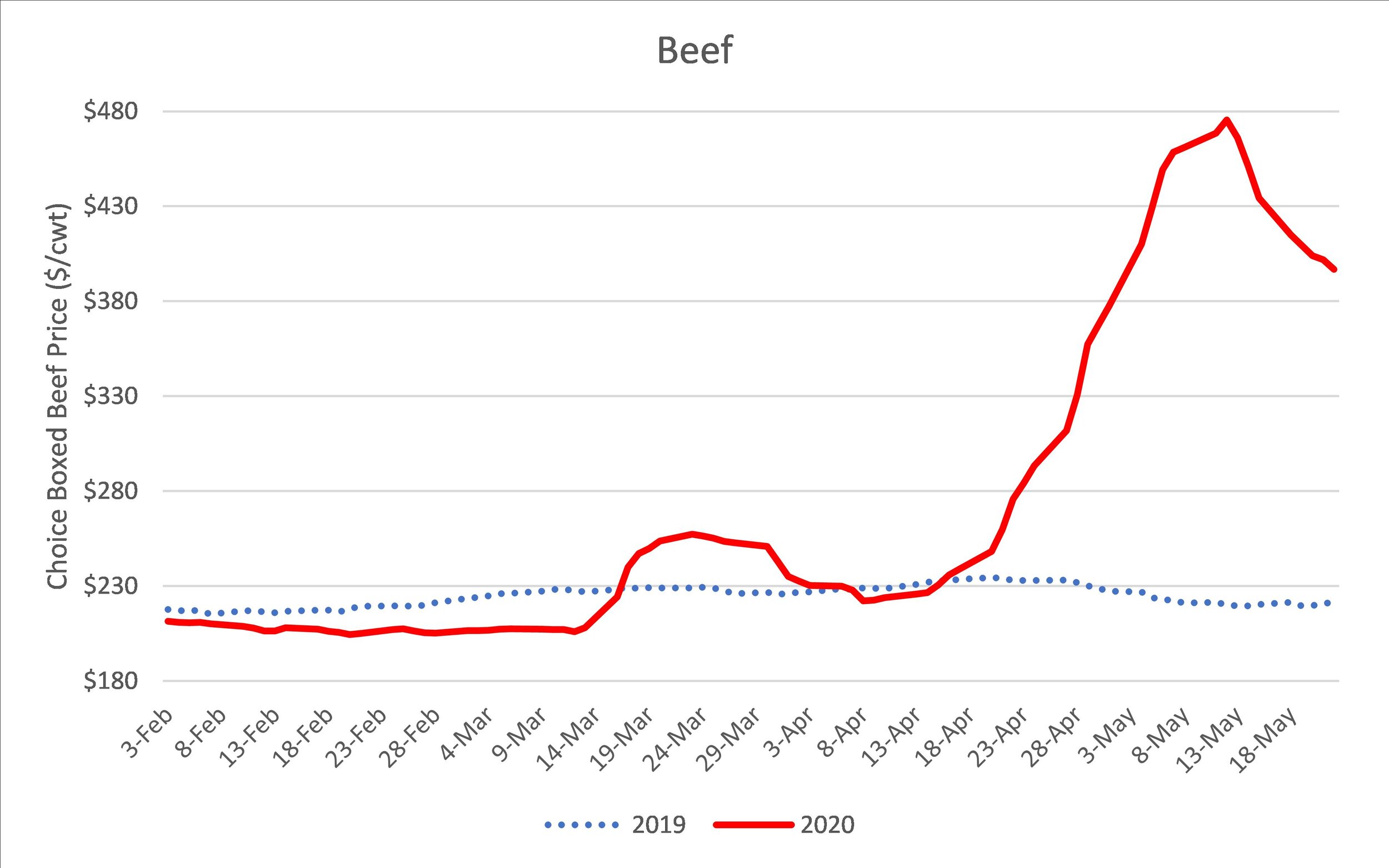

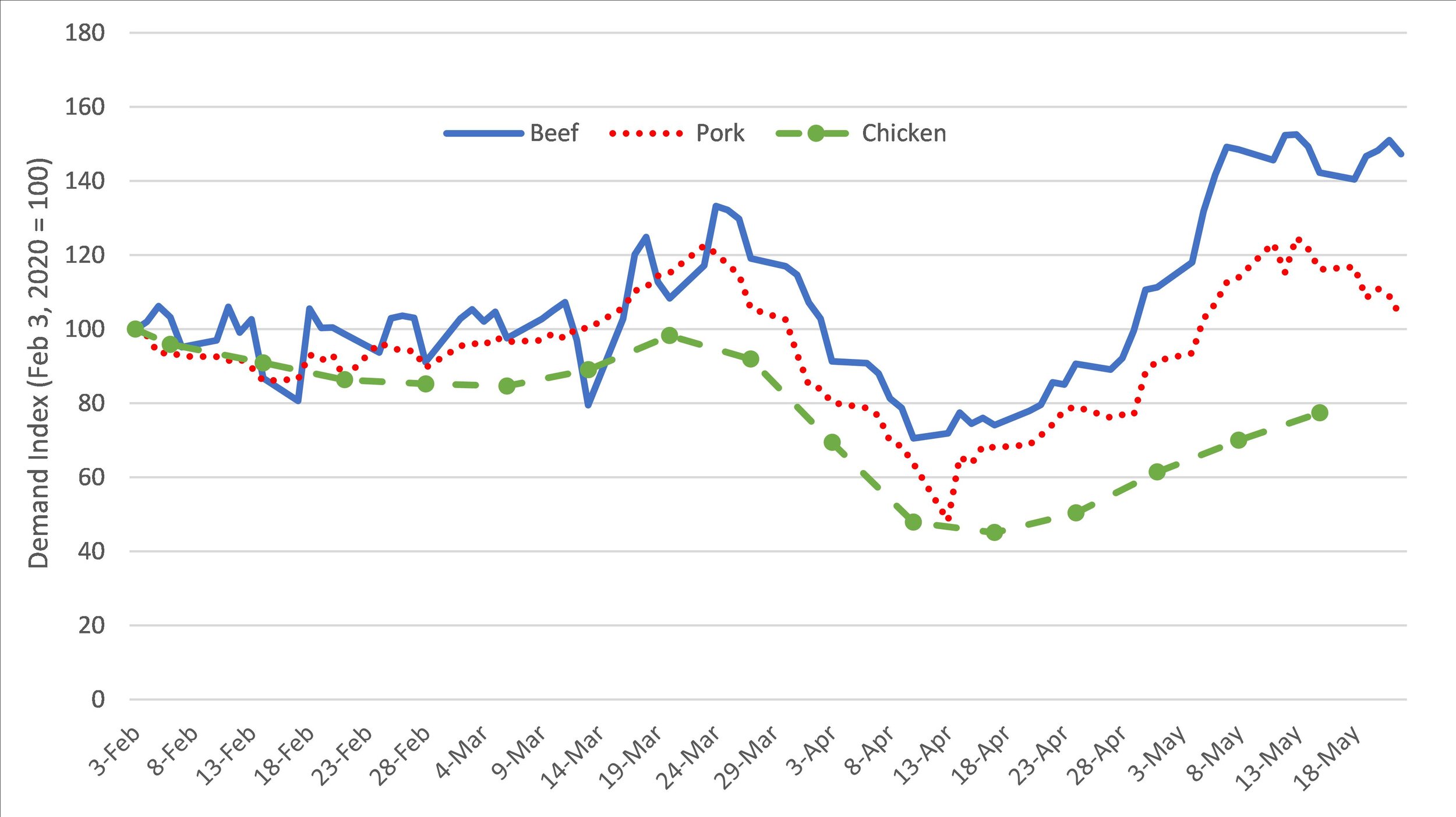

It’s also important to clarify what is meant by “shortage.” Why weren’t there more empty shelves in late April and early May given the reduction in processing volume shown above? The answer: prices. We are going to consume whatever meat gets produced, whether it is a small or large amount. If there is a larger than expected amount of meat being produced, prices need to fall to induce us to consume more than we otherwise would have. By contrast, if a smaller amount of meat is being produced than expected, prices need to rise to induce us to cut back and consume less than we otherwise would have.

Thus, prices are the mechanism by which scarce resources (like meat) get allocated. Retailers sometimes use other non-price mechanisms (like: limit of 2 packages per customer or long wait lines) to ration scarce supplies if they don’t want to pass on the full cost increases to consumers. Higher prices and other mechanisms like store buying limits are what helped prevent many grocery store shelves from being completely empty (i.e., having “shortages”).

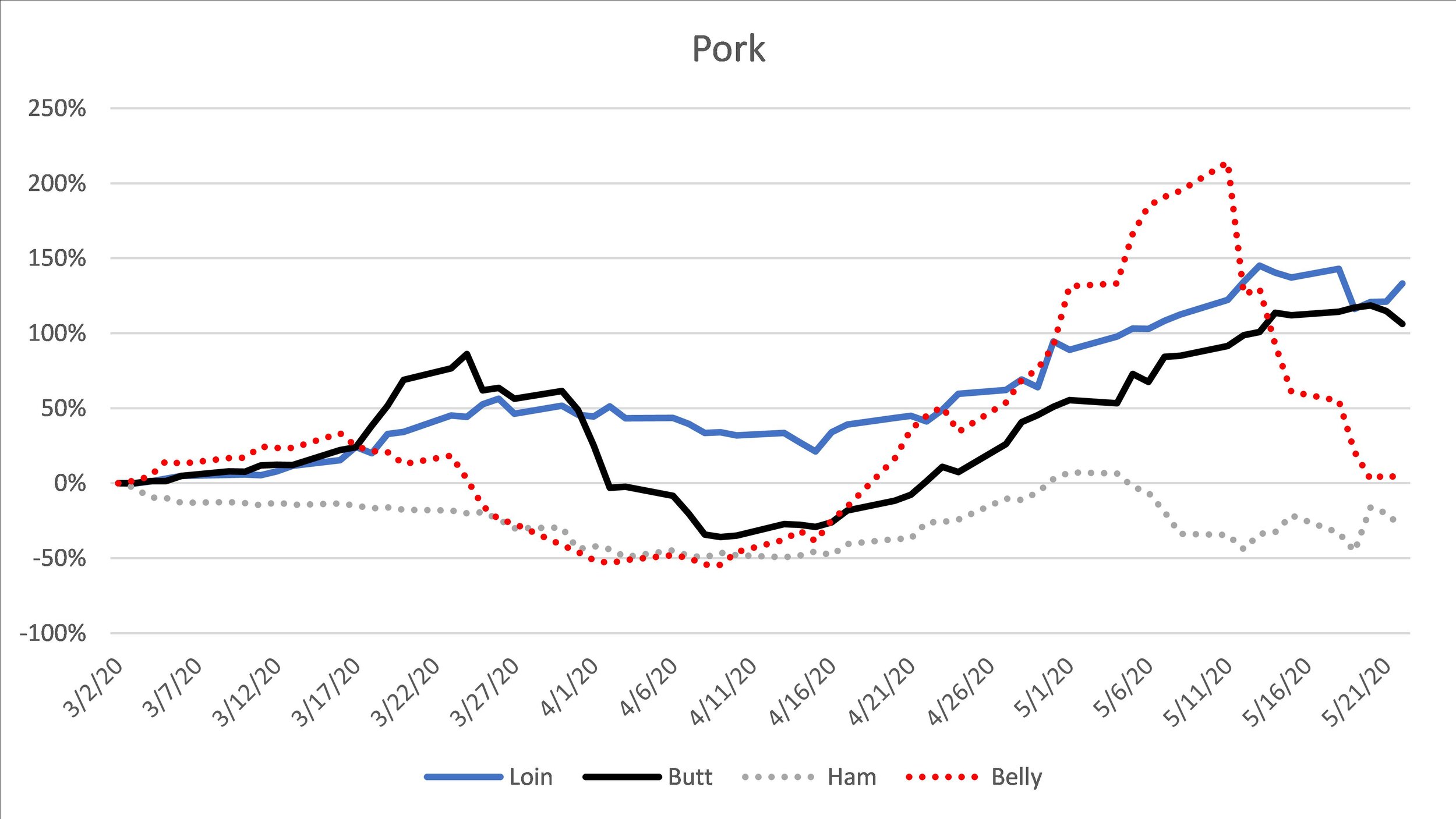

So, did beef and pork prices rise to help allocate the significantly lower quantity being produced? Absolutely! Here’s a graph of changes in wholesale beef and pork prices based on USDA data.

Finally, when discussing trade, I think it is really important to get the timing and trends right. If we want to explore how trade patterns responded to the plant shutdowns and reductions in domestic supplies, we need to look at data in late April and May. As the initial figure above shows, it was really only in mid April that we started seeing very significant reductions in processing volumes, with the “bottom” occurring in early May.

So, what happened to US meat exports? Here are some figures from the US Meat Export Federation (USMEF).

The USMEF defines an export as: “an actual shipment from the U.S. to a foreign country” whereas an “Export sale is defined as a transaction entered into between a reporting exporter and a foreign buyer. Sales can be cancelled or adjusted in following weeks, thus “net” sales are reported as the difference between new sales and any cancellations or adjustments.”

These figures show a sharp drop in sales of beef and pork at the time we starting seeing the worst of the packing plant shutdowns and closures. Actual exports (i.e., movement of meat across the border) also fell, albeit at a slower rate than sales, revealing the lagged nature between when a “sale” is made and when the meat leaves the country. It’s one of the reasons the data showed exports persisting for a few weeks even after plants began to close: the meat had already been sold weeks prior to the plant shutdowns occurring.

Why would exports fall in response to the COVID-related packing plant shutdowns? Perhaps it was patriotic duty on the part of packers to feed American consumers. I suspect the over-riding motivation was economics. As the price data illustrated above clearly shows, packers could fetch a higher price for their meat here at home. That is, packers didn’t have to be coerced into reducing exports as there was a strong economic incentive to sell into domestic markets. Again, we see prices serving as a key mechanism to re-direct meat supplies to help prevent “shortages.”