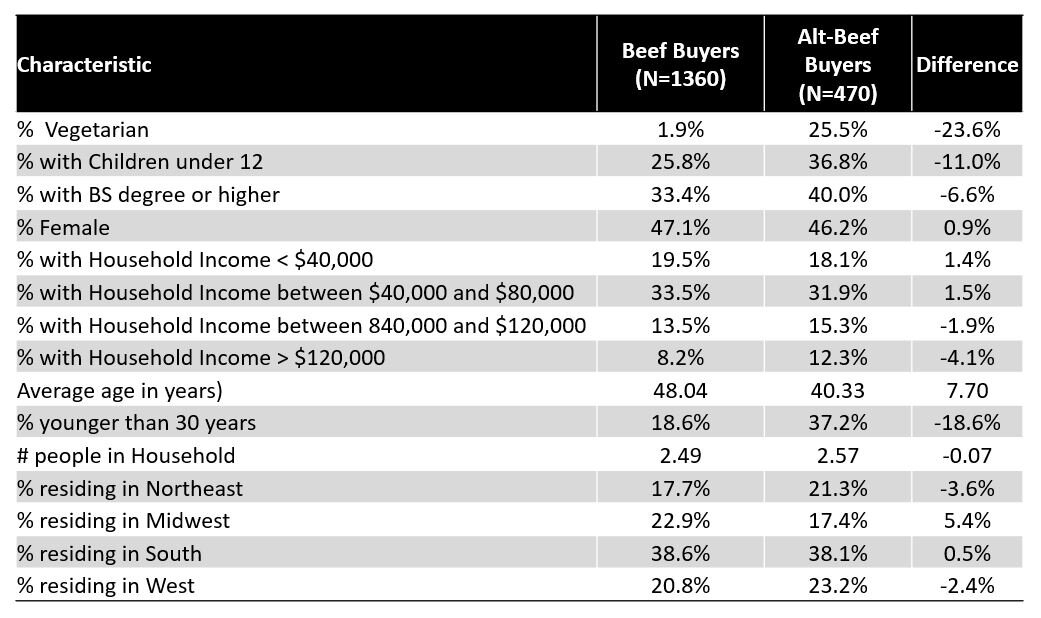

I came across a report from IRI showing changes in sales of plant-based meat alternatives during March, April, and May relative to the same time last year. The figure below shows some dramatic sales growth during the early part of the pandemic. Of course, the large percentage growth is partly explained by the fact that plant-based sales were starting from a low base (i.e., if you go from 1lb to 2lbs, that’s 100% growth, whereas if you go from 100 to 101lbs, that’s only 1% growth). The rest of the report shows the enormous difference in relative magnitudes as plant-based sales are only about 0.66% of total dollar sales (or 0.33% of total lbs of meat sales) .

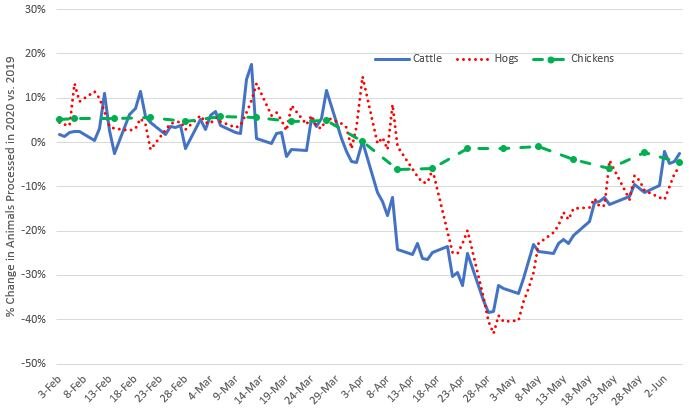

What I want to focus on here though isn’t the spike in sales in March, but rather what happened later. Why wasn’t there a similar spike in sales in April and May? It was in late April and early May that beef and pork production were being most adversely affected from plant shutdowns. During this time, wholesale meat prices were skyrocketing and there were stories in every major media outlet about the possibilities of meat shortages. Data from USDA and the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows retail ground beef prices in grocery stores, for example, jumped more than 10% from April to May (after rising about 5% from March to April).

So, at time when beef prices rose dramatically, retailers were limiting how much beef consumers could buy, and there was overall limited availability of beef, the growth in sales of plant based meats began to fall from almost 80% at the end of April to 57% at the end of May.

At the time the economic environment was most opportune for consumers to switch from beef and pork to plant-based alternatives, it seems that few made that substitution. The figure below shows the trends in volume (or lbs) market share. The share of plant-based sales did indeed rise over the period in question from 0.22% of all lbs purchased to 0.33% of lbs purchased. I’m a bit surprised it wasn’t more.

One of the inferences we can draw from these data, which is also consistent with the research we recently conducted, is that a lot of the purchases of plant-based alternatives are coming from consumers who wouldn’t have bought much beef or pork to begin with.

I look forward to seeing how these trends continue to evolve.