The February 2017 edition of the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) is now out.

From the regular tracking portion of the survey, we find that (compared to one month ago) willingness-to-pay (WTP) decreased for all food products, but most especially for chicken wings and the two non-meat products. For some historical context, I thought I'd also show changes in WTP for steak and ground beef over time and show how they compare with changes in retail prices as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The above graphs reveals three things. First, WTP is not the same thing as a price. WTP is (at least in theory) a "pure" measure of demand, but prices can be affected by demand and by supply-side factors. Second, despite the above statement, it appears there is some relationship between the two measures as the correlations between WTP and prices are 0.44 for ground beef and 0.55 for steak. Third, WTP as measured by FooDS is much more volatile from month-to-month than are prices.

You can read the whole report for the results from the other tracking portions of the survey.

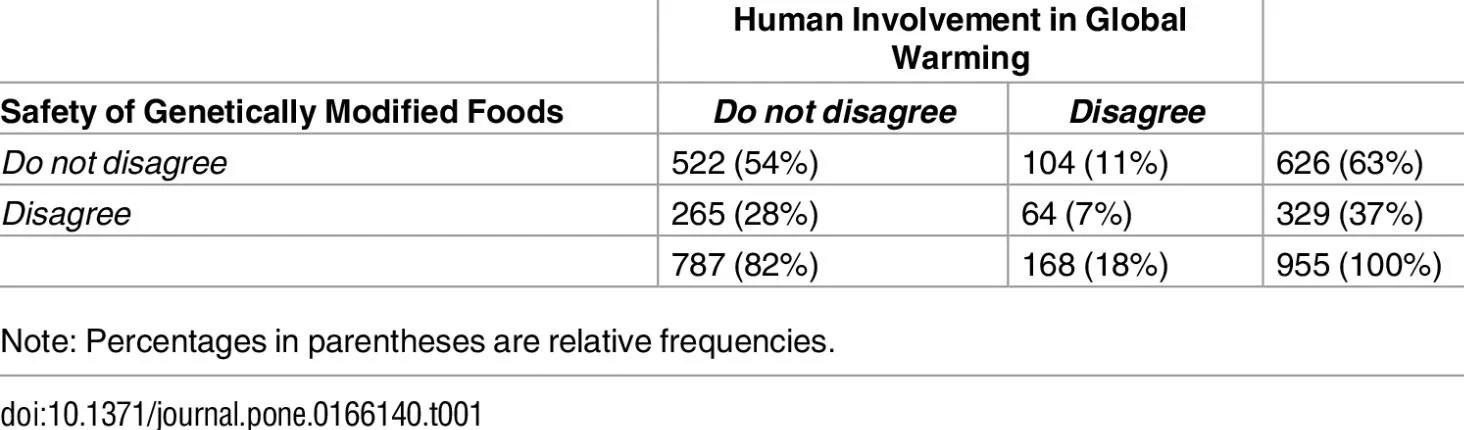

Several new ad hoc questions were added this month to investigate how consumers respond to information about the herbicide glyphosate. Working with one of my Ph.D. students, Trey Malone, we picked this topic because it is one we thought consumers were unlikely to have much knowledge about but for which there had been many news stories written. We were interested, in particular, about forms of confirmation bias - where people seek out information that may confirm their prior beliefs, and by the research in cultural cognition, which suggests we choose information to believe based on our "tribe."

We asked respondent’s willingness-to-pay for organic vs. non-organic apples and granola bars before and after receiving information about glyphosate at GMOs. Respondents were randomly

allocated to one of five treatments. Respondents in the first four treatments were provided an article to read from one of four sources: The Pulse of Natural Health Newsletter, Food Babe, National Review, or Science Magazine. So far this would be a pretty standard study on the effects of information. Then, in the fifth treatment, respondents were allowed to pick which of the four sources of information they wanted to read (they were given the name of the source and the title of the article).

We will report the full results associated with the effects of information on willingness-to-pay later, however, I will note that the “negative” information about glyphosate from Natural Health and Food Babe had a much bigger effect than the “positive” information from National Review and Science Magazine.

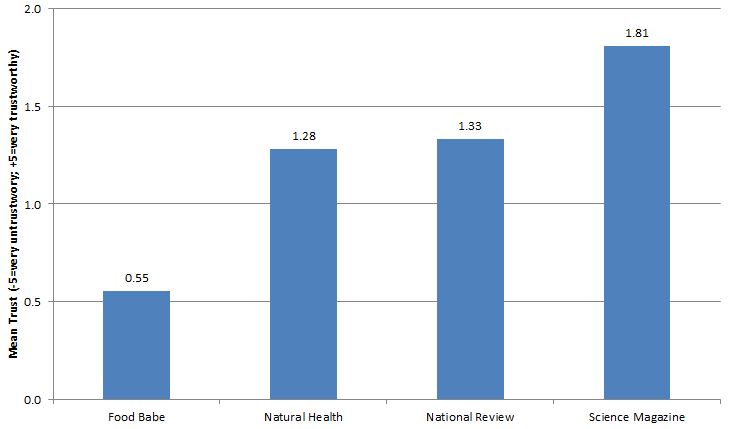

We asked all respondents, “How trustworthy or untrustworthy do you consider each of the following news sources for information regarding food?” They responded on a scale from -5=very untrustworty to +5=very trustworthy. Science Magazine was the most trusted with a mean response of 1.8. Next was National Review at 1.33 followed by Natural Health at 1.28. Far behind (and statistically significantly lower) was the Food Babe at 0.55.

Despite the fact that the Food Babe was the least trusted source of information, in the treatment where individuals could chose which information they wanted to read, 25.4% chose to read the article from the Food Babe. The only source chosen more often was Science Magazine (picked by 40.5% of respondents). Natural Health was picked by 19% and National Review by 15.1%.