Yesterday I had the opportunity to testify before the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry in a hearing about livestock and poultry. A video of the entire hearing is here. My written testimony is also at the link. For convenience, I’ve also reproduced it below.

Chairman Roberts, Ranking Member Stabenow, and Members of the Committee, thank you for inviting me here today. I serve as Distinguished Professor and Head of the Agricultural Economics Department at Purdue University, and I will focus my remarks on six economic issues currently facing livestock and poultry industries: global protein demand and trade, mandatory price reporting, competition, labor, animal disease, and the need for innovation.

Population and income are two key drivers affecting demand for meat and poultry. Slow population growth and concerns about an economic slowdown indicate the potential for depressed meat demand in this country. Health, environment, and animal welfare criticisms, coupled with emerging plant- and lab-based competitive alternatives, are also significant headwinds.

These factors suggest that meat demand growth is largely expected to occur outside the United States. Having access to consumers in other countries has become increasingly important to the livelihood of U.S. livestock and poultry producers. The U.S. exported about 12% of beef, 22% of pork, and 16% of poultry production last year. It is in this context that trade agreements are important to help open markets for US producers to allow products to flow to consumers who value them most.

Some U.S. producers have expressed concerns about the competition from imports, but the U.S. is a net exporter of meat and poultry products, and the types and qualities of meat we import tend to differ from what we export. There have been some calls to renew Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (MCOOL). Congress repealed MCOOL for beef and pork in 2015 to avoid more than $1 billion in retaliatory tariffs after a protracted legal battle with other countries before the World Trade Organization. Our survey and experimental research suggests many consumers indicate they are willing to pay premiums for U.S. meat products; however, research also shows few consumers were aware of actual origin labels when grocery shopping, and analysis of grocery store scanner data did not reveal any significant changes in consumer demand for beef or pork after the implementation of MCOOL. Meat demand indices indicate, if anything, beef and pork demand has increased after the repeal of MCOOL. Cattle prices fell shortly after the repeal of MCOOL, but this is largely explained by an increase in cattle inventory that happened to coincide with the labeling policy change. To the extent consumers are truly willing to pay a premium for U.S. labeled meat that exceeds the costs of tracing and labeling, there remain opportunities for private entities to take advantage of this market opportunity.

The current authority for Livestock Mandatory Reporting (LMR) is set to expire in 2020. LMR was designed to improve transparency, facilitate market convergence, and reduce information asymmetries. Despite these laudable goals, academic research on impacts of LMR is mixed. Shortly after its initial passage in 1999, surveys of cattle producers suggest expectations about the impacts of LMR may have been overly optimistic. Some concerns have been expressed that LMR might facilitate rather than curtail anticompetitive behavior among packers. However, evidence indicates LMR helped facilitate integration of regional markets. It is important for LMR to continue to modernize and be agile in response to the pace of change in the industry. One challenge is the dwindling share of cattle and hogs sold in negotiated or cash markets, which typically serve as the base price in formula contracts. There are significant benefits to formula contracts and more producers are voluntarily choosing this method of marketing over the cash market, but questions remain about the volume of transactions needed in the cash market to facilitate price discovery. A benefit of LMR is the massive amounts of data provided to economists and industry analysts to help understand these and other market dynamics.

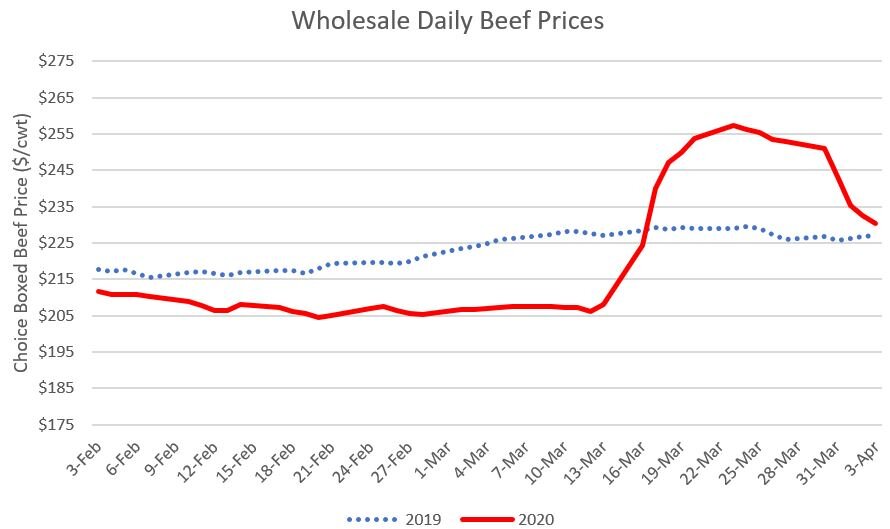

Last month, price dynamics following a fire at a packing plant in Western Kansas renewed discussion about packer concentration and potential anti-competitive behavior. Concerns about anti-competitive behavior in general must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and details about this particular case are still emerging in light of simultaneous market dynamics that were also at play. Available evidence to date suggests the observed reduction in cattle prices and the increase in wholesale beef prices following the fire are not inconsistent with a model of competitive outcomes. An unexpected reduction in processing capacity reduces demand for cattle, thereby depressing cattle prices. The need to bring in additional labor to increase Saturday processing and temporarily re-purposing cow plants for steers and heifers involves additional costs that pushed up the price of wholesale beef. These price dynamics are not surprising and are generally what would be expected from the fundamental workings of supply and demand.

In general, a lack of availability of labor at processing facilities and in transportation have proved significant hurdles for the sector. When processors are unable to secure sufficient workforce to operate facilities at capacity, there is the potential to reduce demand for livestock and poultry, which has much the same price effects witnessed after the Kansas fire.

I also urge the committee to pay close attention to emerging animal disease issues. African Swine Fever (ASF) in China has had a decimating impact on their hog herd and has increased their pork prices by almost 50%. The significant disruption to the Chinese hog supply has reverberated through global agricultural markets, reducing demand for U.S. soybeans and inducing substitution toward alternative proteins such as beef and poultry. While U.S. hog producers have been able to increase exports to China as a result of ASF, exports are not what they could have been had China not raised tariffs on pork. It appears that ASF is spreading beyond China. My calculations suggest that if an outbreak of ASF similar in relative magnitude to the one in China were to occur here, U.S. pork producers could lose about $7 billion/year and U.S. consumer harm would be at least $2.5 billion/year. ASF is not the only animal disease concern, and an outbreak of foot mouth disease, discovery of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or a return of avian influenza or Newcastle disease could have similar devastating impacts. Thus, there is a need for additional funding for research to combat foreign animal disease.

There is also a need for funding to improve the productivity of the livestock and poultry sectors. Productivity growth is the cornerstone of sustainability. For example, had we not innovated since 1970, about 11 million more feedlot cattle, 30 million more market hogs, and 7 billion more broilers would have been needed to produce the amount of beef, pork, and chicken U.S. consumers actually enjoyed in 2018. Innovation and technology saved the extra land, water, and feed that these livestock and poultry would have required, as well as the waste and greenhouse gases that they would have emitted. Investments in research to improve the productivity of livestock and poultry can improve producer profitability, consumer affordability, and the sustainability for food supply chain.