There continues to be high interest in plant-based meat alternatives and speculation about impacts of the emergence of these alternatives on traditional beef, pork, and chicken demand. This past summer, I discussed the results of a consumer study conducted to address some of these issues, but the results relied on pre-pandemic survey data. Have consumer preferences changed? And, how might the emergence of plant-based alternatives affect the entire portfolio of animal-based protein offerings?

As a follow up to the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) I ran monthly for over five years, Glynn Tonsor and I have been running the monthly Meat Demand Monitor (MDM) since February 2020. The MDM contains a series of 9 simulated grocery shopping choices where people indicate which, if any, protein product they’d buy at different price levels when shopping. Below is an example choice.

As you’ll notice in the above question, one of the choice options is a plant-based patty. Every month, Glynn has released results of the MDM survey reporting the percent of times the plant-based patty is chosen out of this set of 8 meal options (plus a ninth “none of these”). Say what you may about the merits of survey questions, but the advantages of tracking surveys is that we can at least see if there are significant trends or changes from one month to the next. Below is a graph showing the trends in market shares of two of the items over time.

Throughout 2020, plant-based patties have consistently been chosen about 3% of the time in comparison to ground beef, which is chosen about 24% of the time. The ~3% market share for plant-based patties is much smaller than the estimates I’d previously reported from my study with Ellan van Loo and Vincenzina Caputo. Part of the explanation for the discrepancy is that the the choice set used in the MDM contains many more options, so of course the share of any one item is likely to be smaller. The other explanation could be that people who choose plant-based patties might have instead chosen something other than ground beef. That is, some of the people who would choose a plant based patty in a binary choice between ground beef and plant-based instead choose something different, like a chicken breast, when presented a larger set of meal options.

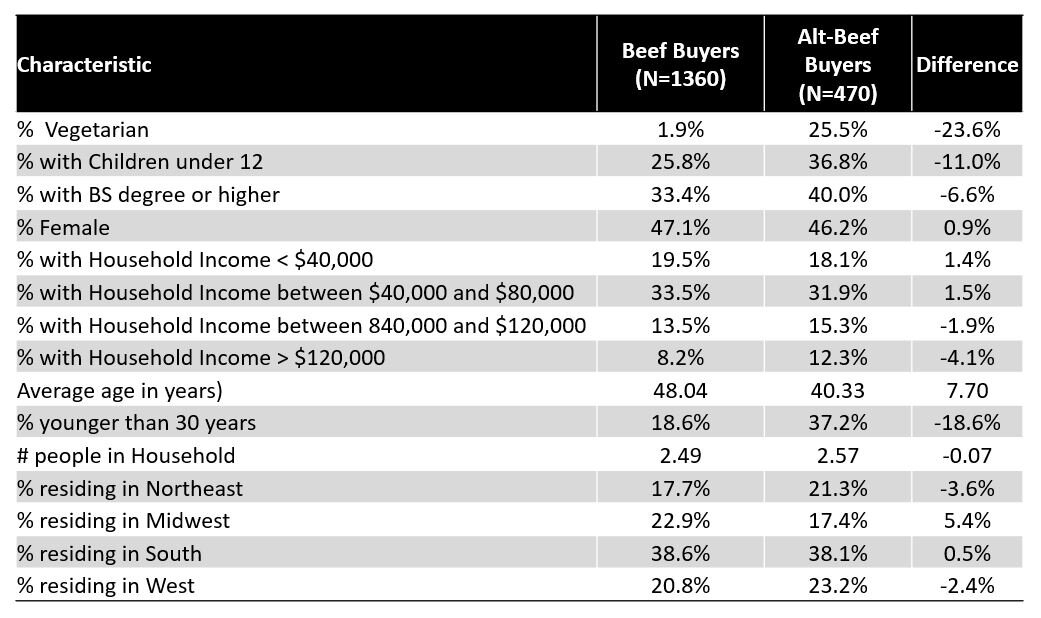

To explore this issue in a bit more detail, I took the data from the August through December 2020 versions of the MDM associated with retail grocery choices (all the data and description of underlying methods is here). The data consist of 36,018 choices made by 4,002 consumers (a bit under 1,000 each month). I estimated a choice model that allows for flexible substitution patterns and utilize the estimates to predict which options people would choose in different conditions.

At the average price levels, I predict about 3% of consumers would choose the plant-based patty. This isn’t surprising as it simply confirms the findings in the figure above. Here is perhaps a more interesting question. Of the roughly 3% of consumers who chose the plant-based patty: what would they have chosen instead if the plant-based patty wasn’t available? The model-based prediction is below. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, about the same number of people would have instead have chosen chicken breast as ground beef. Only 6% were predicted to have not have chosen one of the other items on this list.

What about price elasticities? The model suggests that for every 1% reduction in the price of plant-based patties, there is a 3.08% increase in market share of plant-based patties (this is the own-price elasticity of demand). This same 1% reduction in the price of plant-based patties would reduce the market share of bacon and shrimp by about 0.12% each, reduce the market share of ribeye and pork chops by about 0.10% each, and ground beef by about 0.08% (these are the cross-price elasticities). Thus, the estimates suggest very little substitution caused by small marginal price changes.

Some of the above results stem from the fact that, based on current market data, the plant-based patty had an average price of $11.99lb whereas ground beef was assumed to be $4.49/lb. What if both were priced at $4.49? Assuming this dramatic price reduction for plant based, the model predicts the market share for plant-based would jump from about 3% to about 22%, lagging only chicken breast at 22.1%. In this scenario, ground beef is projected to take 18% market share. One caveat is that this scenario presumes a much larger price change than we used in the survey (so it is a projection outside the range of choices we actually observed).

This is a fluid situation and there remains much to be learned. Along with Ted Schroeder, Glynn and I have recently completed a series of new studies on the possible impacts of plant-based alternatives on beef demand. I hope be able to release those results in the coming weeks.