In a recent article, Matthew Yglesias takes issue “that conventional wisdom seems to have settled on the idea that there was a sharp uptick in obesity starting around 1980.” He argues instead that body weights have been increasing for a long time, and that if we are looking for causes of weight gain and obesity, we need to take a longer view than simply asking “what changed” in 1980, which seems fashionable today in the Twittersphere.

Here are his final two paragraphs on possible drivers of weight gain over the past century.

“It just turns out that like a lot of things, this has some downsides. The question of what, if anything, to do about those downsides seems pretty difficult to me, but I don’t think its origins are a big causal mystery.

If anything, making the origins out to be some huge puzzle lends itself to the false suggestion that there’s a very simple and straightforward solution. The truth — that we are experiencing some downside to living in a society with a great deal of material abundance — is harder to wrestle with, since people would be pretty unhappy about policy changes that reversed the 100+ year trend toward food becoming tastier, more available, and more convenient.”

I agree - perhaps because it is awfully similar to the conclusion I reached back in 2013 in The Food Police. Here’s what I wrote then at the conclusion of the chapter on fat taxes.

“It is only reasonable that we eat a little more food when it costs less and give up manual labor when an air conditioned office job comes along. We can’t disentangle all the bad stuff we don’t like about obesity with all the good things we now enjoy, such as driving, eating snacks, cooking more quickly, and having less strenuous jobs. Yes, we can have less obesity, but at the costs of things we enjoy.

When you hear we need a fundamental change to get our waistlines back down to where they were three decades ago, beware that it might take a world that looks like it did three decades ago.”

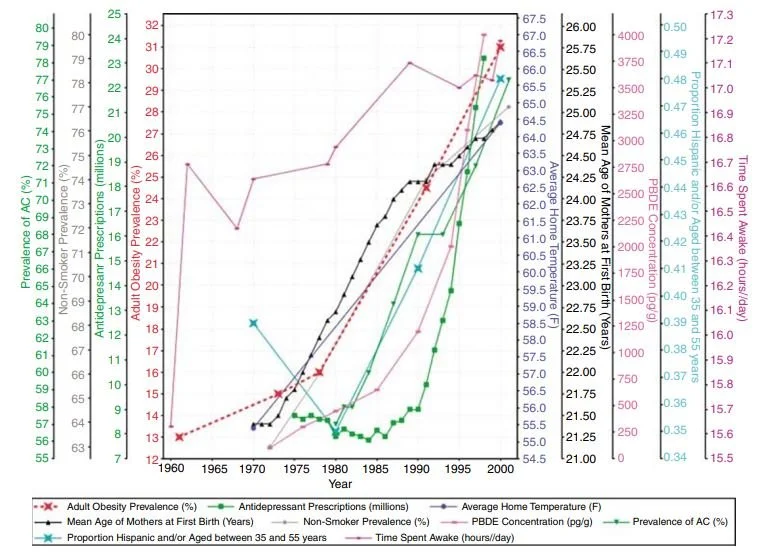

We are unlikely to finding a simple, mono-causal explanation for the rise in obesity. That is perhaps best illustrated in the figure below from a 2006 paper by Keith et al. in the International Journal of Obesity, which plots obesity (the red dashed line with x’s) alongside either other factors that have been suggested as causes for obesity. Obviously, lots of strong positive correlations, but it shows the likely futility of finding one single, easy answer.