Last week was a whirlwind of trip and event cancellations, movement of courses online, and the dusting off of emergency and contingency plans. This week is likely to bring more social-distancing and quarantining measures. The ultimate toll and impacts of the coronavirus are highly uncertain at present. Nonetheless, it might be useful to speculate a bit about impacts of coronavirus and the events surrounding it on food markets.

1. Grocery buying behavior. It has been fascinating to watch online, and in my own local grocery stores, which items consumers are choosing to stock-up on. The run on toilet paper, for example, seems on the surface of it, downright irrational. After all, COVID-19 does not cause digestive issues. As irrational as the initial movement to toilet paper may seem, it isn’t crazy for subsequent consumers to then stock up too. After all, it doesn’t take much for a reasonable person to see that if all other consumers are buying up all the toilet paper, that they’d better off getting theirs before none is left. There is a long and interesting economics literature on information cascades and herding behavior, which shows that even if you disagree with what other people are doing, it is sometimes sensible to go along with the crowd.

Much of the information we have at this point on which items are stocking-out is anecdotal, but there do seem to be some common trends in what I see in my own local stores and commentary online. For example, it seems many of the new plant-based burgers are being left behind while the rest of the meat case is being cleared (see here or here). I was surprised to see in my own local store, that virtually all the beef was gone (except for a bit of ground beef), about half the pork was gone, and chicken was plentiful. This must say something about people’s psychology to go for the highest-price, perishable produce in this time of panic; that or differences in supply chain issues, but more on that later. In other aisles, rice and pasta went quickly, presumably for issues related to the long shelf life, should quarantining result. Still, I noticed what was left in those aisles were the gluten-free options and the lesser-known brands or unusual flavors, suggesting stock-outs are related to item popularity. I hope we can learn more about this behavior after the fact. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to study stocking-out phenomenon because stores are usually well stocked, and because grocery store scanner data only shows us what people bought, but we can’t see what people didn’t buy because it wasn’t available.

2. Stock-outs and supply chains. The New York Times ran a story yesterday with the heading “There Is Plenty of Food in the Country.” I largely agree. The stock-outs we are seeing now are likely temporary disruptions resulting from consumers pulling forward buying behavior in anticipation of future reduce mobility. But, it’s unlikely people will eat more in aggregate because of the coronavirus. Thus, this is largely a temporal adjustment in buying behavior with smaller effects on aggregate food demand.

However, there could be more serious food market disruptions. Some of the stock-outs and slowdowns in grocery check-out lines are because employees are staying at home and practicing social-distancing. This problem is likely to grow if more people become ill. So, while we might have the food supply available, will we have the workers to get it to us?

Now, take a step back in the supply chain, and this is where worker issues could have serious issues. Remember all the fervor over the beef packing-plant fire back in August? While the impacts was counter-intuitive to many producers, the economics were straightforward: an unexpected disruption in supply depressed cattle prices and boosted wholesale beef prices. It isn’t far-fetched to imagine worker illnesses getting to the point that plants have to temporarily shut down on a scale that is at least as large as the August-fire, which removed about 5% of the nation’s beef processing capacity. One difference is that destroying a plant via fire is not the same as temporarily closing plants due to lack of healthy workers; one resulted in a long-term price adjustment while the latter is more likely a temporary price fluctuation.

One thing that makes me nervous even about temporary closures, if large scale, is the animals that have been placed to be market-weight in the next few weeks. While feedlot cattle can likely remain on feed a few weeks longer with relatively small changes in profitability, that is less true for hogs, and particularly chickens. Meat supply chains are optimized for efficiency and low-cost production, not necessarily for flexibility and resiliency.

A signal to keep an eye on is the amount of meat in cold storage (the data currently available are lagged by at least a month). The buying behavior we’re seeing now is likely to pull meat out of storage and onto our dinner plates. However, that boost in domestic demand is likely to be offset by reductions in foreign demand, and the coronavirus has hit hard some of our biggest export markets.

The flip-side of this is that we rely on imports from China for a variety of consumer goods, and this trade is likely to be disrupted by coronavirus. I’ve often been critical of the local foods movement, but it’s times like these that highlight some of the benefits of localization and heterogeneity in the food supply chain.

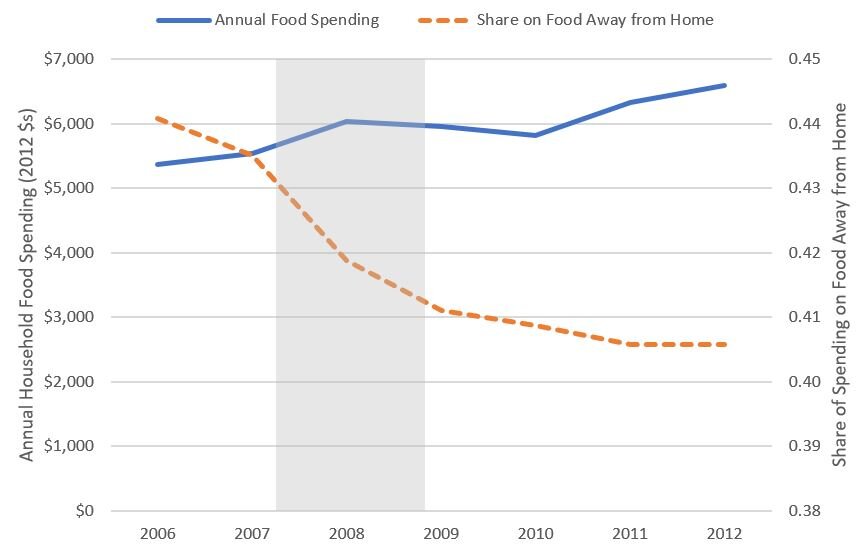

3. Recession. Given the reaction of the stock-market and the disruption to normal business and spending activity, the chances of a recession are high. The “Great Recession” in 2007-09 had significant impacts on food spending, particularly spending on food away from home. Here are data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey. These data show food spending at home only declined slightly after the recession, but the share of spending that occurred outside the home (at restaurants, etc.) fell from 0.44 to 0.41.

It is also interesting to look at how spending on different types of food changed during the Great Recession. The figure below shows spending on food eaten at home (plus total alcohol spending). All at-home food spending increased in 2008 before falling in 2009, but the increase was smaller for beef and pork, which implies the share of food spending on these items fell over this period. Spending on alcohol took the biggest hit. By contrast, spending on fruits and vegetables, cereal and bakery, and dairy, fared pretty well during the last recession.

There is an old saying that “generals are always fighting the last war.” Likewise, it is probably wise not to focus too much on the past recession to predict how consumers might respond to one potentially caused by the coronavirus. Nonetheless, the pattern of reduced spending on food away from home is already occurring, and meat demand is typically thought to respond significantly to income, which suggests, at least in these two cases, the pattern may re-emerge.

During the past recession, rates of food insecurity spiked. There are concerns about impacts of school closures on childhood food security, and the USDA is considering policies that will allow delivery of free school lunch and breakfast to low income children even in instances where schools are closed.

4. Population. A couple months ago, I discussed the role of population in affecting food demand. I was writing then about the fact that birth rates have been falling, and indicated a smaller population would put downward pressure on food prices and farm incomes. Unfortunately, a global pandemic like the coronavirus has the potential to reduce the world’s population (or at least slow the increase). For example, estimates suggest the flu pandemic in 1918 sickened about 27% of the world’s population and killed about 2 to 3% of the world’s population at the time. Estimates of the potential number of deaths from the coronavirus are all over the board, but the greater the number of “excess” deaths, the greater the reduction in aggregate food demand. On the up-side, all this social-distancing and self-quarantining means many more couples will be home together. We may need to hang on to all those hospital beds for the new babies that will arrive in nine months.