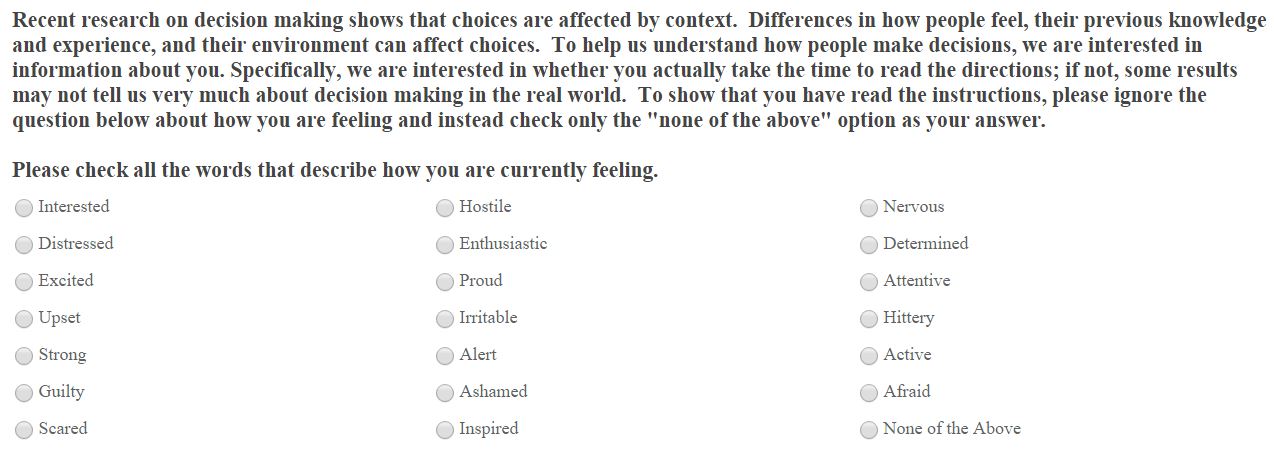

Imagine taking a survey that had the following question. How would you answer?

If you answered anything but "None of the Above", I caught you in a trap. You were being inattentive. If you read the question carefully, the text explicitly asks the respondent to check "None of the Above."

Does it matter whether survey-takers are inattentive? First, note surveys are used all the time to inform us on a wide variety of issues from who is most likely to be the next US president to whether people want mandatory GMO labels. How reliable are these estimates if people aren't paying attention to the questions we're asking? If people aren't paying attention, perhaps its no wonder they tell us things like that they want mandatory labels on food with DNA.

The survey-takers aren't necessarily to blame. They're acting rationally. They have an opportunity cost of time, and time spent taking a survey is time not making money or doing something else enjoyable (like reading this post!). Particularly in online surveys, where people are paid when they complete the survey, the incentive is to finish - not necessarily to pay 100% attention to every question.

In a new working paper with Trey Malone, we sought to figure whether missing a "long" trap question like the one above or missing "short" trap questions influence the willingness-to-pay estimates we get from surveys. Our longer traps "catch" a whopping 25%-37% of the respondents; shorter traps catch 5%-20% depending on whether they're in a list or in isolation. In addition, Trey had the idea of going beyond the simple trap question and prompting people if they got it wrong. If you've been caught in our trap, we'll let you out, and hopefully we'll find better survey responses.

Here's the paper abstract.

“This article uses “trap questions” to identify inattentive survey participants. In the context of a choice experiment, inattentiveness is shown to significantly influence willingness-to-pay estimates and error variance. In Study 1, we compare results from choice experiments for meat products including three different trap questions, and we find participants who miss trap questions have higher willingness-to-pay estimates and higher variance; we also find one trap question is much more likely to “catch” respondents than another. Whereas other research concludes with a discussion of the consequences of participant inattention, in Study 2, we introduce a new method to help solve the inattentive problem. We provide feedback to respondents who miss trap questions before a choice experiment on beer choice. That is, we notify incorrect participants of their inattentive, incorrect answer and give them the opportunity to revise their response. We find that this notification significantly alters responses compared to a control group, and conclude that this simple approach can increase participant attention. Overall, this study highlights the problem of inattentiveness in surveys, and we show that a simple corrective has the potential to improve data quality. ”