A lot of the debate and discussion surrounding public policies toward controversial food and agricultural issues like GMOs or climate change revolves around public sentiment. We ask people survey questions like "Do you support mandatory labeling of GMOs?" However, as I've pointed out, consumers may not even want to have to make this sort of decision; they would prefer to defer to experts. Thus, we're presuming a level of understanding and interest that consumers may not actually have. This is related to the recent discussion started by Tamar Haspel in the Washington Post about whether the so-called food movement is large or small. Are "regular" people actually paying much attention to this food stuff that occupies the attention of so many journalists, researchers, writers, and non-profits?

I had these thoughts in mind as I went back and looked at this post by Dan Kahan who took issue with Pew's survey on public opinions about GMOs (this was the survey that attracted a lot of attention because it showed a large gap in public and scientific opinion on GMOs). Kahan wrote:

“the misimpression that GM foods are a matter of general public concern exists mainly among people who inhabit these domains, & is fueled both by the vulnerability of those inside them to generalize inappropriately from their own limited experience and by the echo-chamber quality of these enclaves of thought.”

and

“That people are answering questions in a manner that doesn’t correspond to reality shows that the survey questions themselves are invalid. They are not measuring what people in the world think—b/c people in the world (i.e., United States) aren’t thinking anything at all about GM foods; they are just eating them.

The only things the questions are measuring—the only thing they are modeling—is how people react to being asked questions they don’t understand. ”

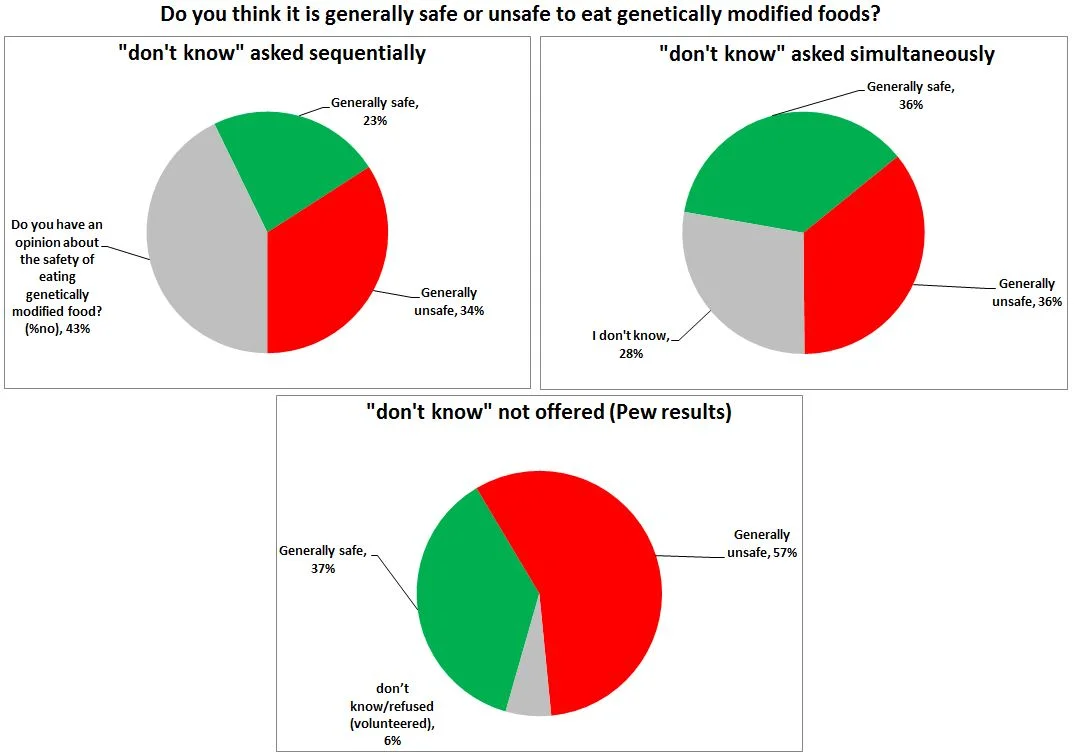

This let me to think: what if we asked people whether they even wanted to express an opinion about GMOs? So, in the latest issue of my Food Demand Survey (FooDS) that went out last week, I did just that. I took my sample of over 1,000 respondents and split them in half. For half of the sample, I first asked, "Do you have an opinion about the safety of eating genetically modified food?" Then, only for people who said "yes", I posed the following: "Do you think it is generally safe or unsafe to eat genetically modified foods?" For the other half of the sample, I just asked the latter question about safety beliefs and added the option of "I don't know". This question, by the way, is the same one Pew asked in their survey, and they didn't even offer a "don't know" option - it had to be volunteered by the respondent. So, what happens when you allow for "I don't know" in these three different ways?

When "don't know" is asked 1st in sequence before the safety question, a whopping 43% say they don't have an opinion! By contrast, only 28% say "don't know" when it is offered simultaneously with the safety question. And, as the bottom pie graph shows, only about 6% of respondents in the Pew survey voluntarily offer "don't know". Thus, I think Kahan's critique has a lot of merit: a large fraction of consumers gave an opinion in the Pew survey, when in fact, they probably didn't have one when this option was allowed in a more explicitly matter.

Moreover, allowing (or not allowing) for "don't know" in these different ways generates very different conclusions about consumers' beliefs about the safety of GMOs. Conditional on having an opinion, the percent saying "generally safe" varies from 40% in the sequential question to 50% in the simultaneous question to 39% in the Pew format which didn't offer "don't know." That support can vary so widely depending on how "don't know" is asked is hardly indicative of stable, firm, beliefs about GMOs among the general public.

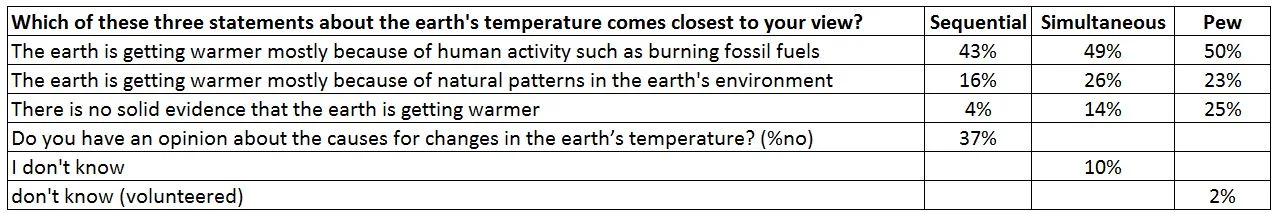

In last week's survey I also carried out the same exercise regarding Pew's questions on climate change. For half of my sample, I first asked whether people had an opinion about the causes of changes in the earth's temperature; for the other half, I included "don't know" as an option simultaneous with the question itself. Here are the results compared to Pew's, which again did not explicitly offer a "don't know."

Again, we see big differences in the extent to which "don't know" is expressed depending on question format, varying from 37% in the sequential version to only 2% in Pew's survey. In this case, it appears that people who would have said "don't know" in the sequential question format are more likely to pick response categories that disagree with scientists, when they are given questions where "don't know" isn't so explicitly allowed.

What can we learn from all this? Just because people express an opinion on surveys doesn't mean they actually have one (or at least not a very firmly held one).