There seems to be a lot of angst these days about food waste. Last month, National Geographic focused a whole issue on the topic. While there has been a fair amount of academic research on the topic, there has been comparatively little on the economics of food waste. Brenna Ellison from the University of Illinois and I just finished up a new paper to help fill that void.

Here's the core motivation.

“Despite growing concern about food waste, there is no consensus on the causes of the phenomenon or solutions to reduce waste. In fact, many analyses of food waste seem to conceptualize food waste as a mistake or inefficiency, and in some popular writing a sinful behavior, rather than an economic phenomenon that arises from preferences, incentives, and constraints. In reality consumers and producers have time and other resource constraints which implies that it simply will not be worth it to rescue ever last morsel of food in every instance, nor should it be expected that consumers with different opportunity costs of time or risk preferences will arrive at the same decisions on whether to discard food”

So, what do we do?

First, we create a conceptual model based on Becker's model of household production to show that waste is indeed "rational" and responds to various economic incentives like time constraints, wages, and prices.

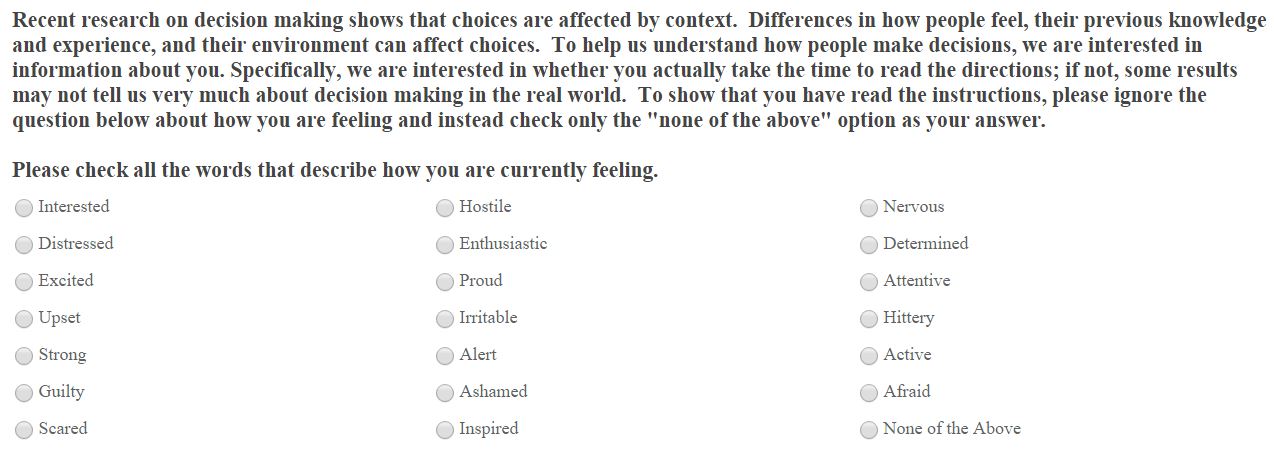

We use some of these insights to design a couple empirical studies. One problem is that it is really tough to measure waste. And, people aren't likely to be very accurate at telling you, on a survey, how much food they waste. Thus, we got a bit creative and came up with a couple vignette designs that focused on very specific situations.

In the first study, respondents were shown the following verbiage. The variables that were experimentally varied across people are in brackets (each person only saw one version).

“Imagine this evening you go to the refrigerator to pour a glass of milk. While taking out the carton of milk, which is [one quarter; three quarters] full, you notice that it is one day past the expiration date. You open the carton and the milk smells [fine; slightly sour]. [There is another unopened carton of milk in your refrigerator that has not expired; no statement about replacement]. Assuming the price of a half-gallon carton of milk at stores in your area is [$2.50; $5.00], what would you do?”

More than 1,000 people responded to versions of this question with either "pour the expired milk down the drain" or "go ahead and drink the expired milk."

Overall, depending on the vignette seen, the percentage of people throwing milk down the drain ranged from 41% to 86%.

Here are how the decision to waste varied with changes in the vignette variables.

The only change that had much impact on food waste was food safety concern. The percentage of people who said they'd discard the milk fell by 38.5 percentage points, on average, when the milk smelled fine vs. sour. The paper also reports how these results vary across people with different demographics like age income, etc.

We conducted a separate study (with another 1,000 people) where we changed the context from milk to a meal left-over. Each person was randomly assigned to a group (or vignette), where they saw the following (experimentally manipulated variables are in brackets).

“Imagine you just finished eating dinner [at home; out at a restaurant]. The meal cost about [$8; $25] per person. You’re full, but there is still food left on the table – enough for [a whole; half a] lunch tomorrow. Assuming you [don’t; already] have meals planned for lunch and dinner tomorrow, what would you do?”

People had two response options: “Throw away the remaining dinner” or “Save the leftovers to eat tomorrow”.

Across all the vignettes, the percent throwing away the remaining dinner ranged from 7.1% to 19.5%.

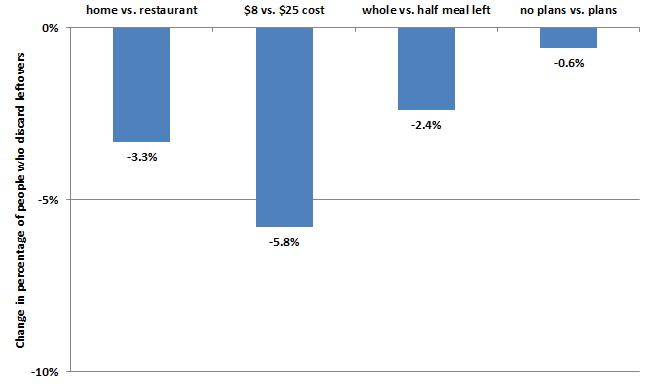

Here are how the results varied with changes in the experimental variables.

Meal cost had the biggest effect. Eating a meal that cost $25/person instead of one that cost only $8/person reduced the percentage of people discarding the meal by an average of 5.8 percentage points. People were also less likely to throw away home cooked meals than restaurant meals.

There's a lot more in the paper if you're interested.