It seems there is a constant barrage of studies, books, and media critical of animal agriculture. The negative publicity is multifaceted and ranges from concerns about animal welfare, health impacts, food safety, climate change, environmental impacts, water usage, food security, and on an on.

Just to given one representative example, here is James McWilliams writing in the New York Times in a 2012 article entitled The Myth of Sustainable Meat:

THE industrial production of animal products is nasty business. From mad cow, E. coli and salmonella to soil erosion, manure runoff and pink slime, factory farming is the epitome of a broken food system.

He argues there, and in a more recent 2014 editorial in the same outlet that we the best solution is to give up eating meat. I used McWilliam as an example, but I could have picked any number of high profile books (e.g., here or here), academics, advocacy groups (e.g., here or here), or news stories that paint conventional animal production industries in a less than favorable light.

Here is my question: how much impact, if any, has this had on consumers' demand for meat, dairy, and eggs?

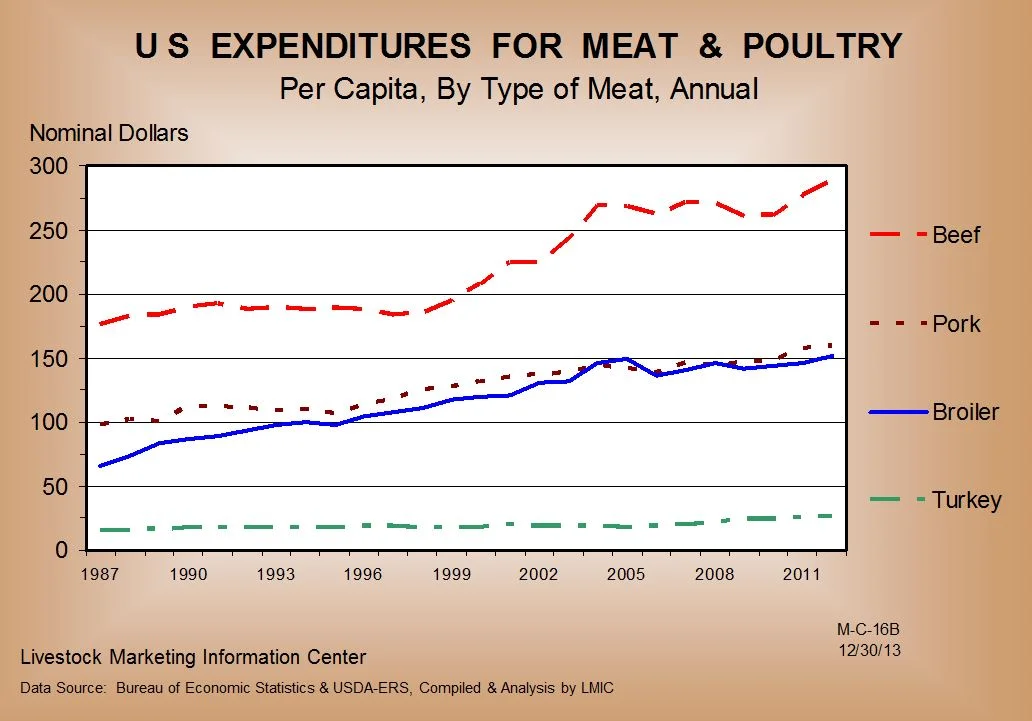

To indirectly get at this question, I turned to some data collected by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) on Personal Consumption Expenditures. The BEA reports total expenditures on food at home in a variety of categories going back to 1959. I took this data and calculated the share of total expenditures on food eaten at home (what the BEA calls " Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption") attributable to beef, pork, poultry, eggs, and dairy products. For reference, total expenditures on food eaten at home was about $61.5 billion in 1959 (in 1959 dollars) and was about $884 billion in 2013 (in 2013 dollars).

There was a remarkable downward trend in the allocation of consumers' food budget away from dairy and beef from 1959 till the early 1990s, and an uptick in poultry. Consumers went from spending about 12-14% of their food budget on beef and another 12-14% on dairy in the early 1960s down to about 5-8% on each in the early 1990s. Stated differently, consumers just about halved the proportion of their food budget going toward beef and dairy in a 30 year time period.

There were a lot of reasons for these changes. These industries became much more productive and prices fell, so consumers could allocate less of their budget to these items but still consume the same amount or more. The price of poultry fell much more rapidly than the price of beef, and thus some of the downward trend reflects substitution away from beef toward poultry. There were other consumer concerns during that period related to cholesterol, saturated fat, E coli, etc. that led to less consumption of beef and dairy.

Despite, all that, it is remarkable how resilient meat demand has been over the last 20 years in light of the large amount of negative publicity mentioned earlier. To illustrate, here is the graph just from 1993 to 2013.

The lines are essentially flat. People are allocating just about the same amount of their food budget to beef, pork, dairy, poultry, and eggs today as they did 20 years ago.

It may be the case that all the aforementioned negative publicity in recent years will eventually cause consumers to allocate their food budget away from animal products. But, at least so far, it doesn't seem to have had much of an impact.