The July 2016 edition of the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) is now out.

Results reveal a reversal in the three-month slide in demand for meat products. Willingness-to-pay (WTP) increased for all food products in July; there were sizeable increases in WTP for steak WTP (+46.44%) and deli ham (+33.15%) from June to July. This month, WTP for steak reached its highest point since FooDS began in May 2013. Compared to one year ago (July 2015), WTP is higher for all food products.

Results also suggest an increase in spending at food away from home. Compared to June expenditures on food away from home were up 6.3% and there was a near doubling in plans to eat out more in July compared to June.

Another major development was that this was the first time that farm animal welfare ranked in the top three issues of concern (behind E. Coli and Salmonella) since the beginning of FooDS.

This month three new ad-hoc questions were added.

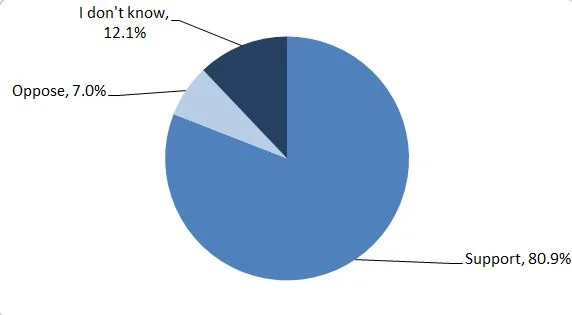

The first dealt with the new GMO labeling bill I mentioned a couple days ago, which has been passed by the Senate and currently being considered by the House. Participants were asked: “The US Congress is considering a bill that would require food companies to disclose whether a food contains genetically engineered ingredients. Food companies can comply by placing

text on packaging, provide a QR (Quick Response) code, or by directing consumers to a phone number or website. Do you support or oppose this legislation?”.

Approximately 81% of respondents stated they would support the bill, 7% said they would oppose the bill, and just over 12% of respondents stated “I don’t know”.

At this point, we should all know these sorts of questions can be a bit misleading as consumers have very little information about the issue and can be shown to support other absurd policies like DNA labeling. However, I'd read these results to suggest that mandatory GMO labels that include disclosure via QR codes do not substantively decrease consumer support for the policy.

Second, participants were asked “Where do you tend to receive the most helpful and accurate information about food health and safety issues? (pick one issue)” Then 14 different sources were listed.

Local television news was listed most frequently as the most helpful and accurate information source (17%), while 11.7% of respondents said evening or nightly television news shows were the most helpful. Only 2.54% of participants listed books are their most helpful source of information. 5.37% of participants stated “other” as their most helpful source of information. Those who selected “other” gave examples including “NatrualNews.com”, “my own online research”, “Institute of Food Technologists mailing list”, “local highly educated farmer”, and “internet”.

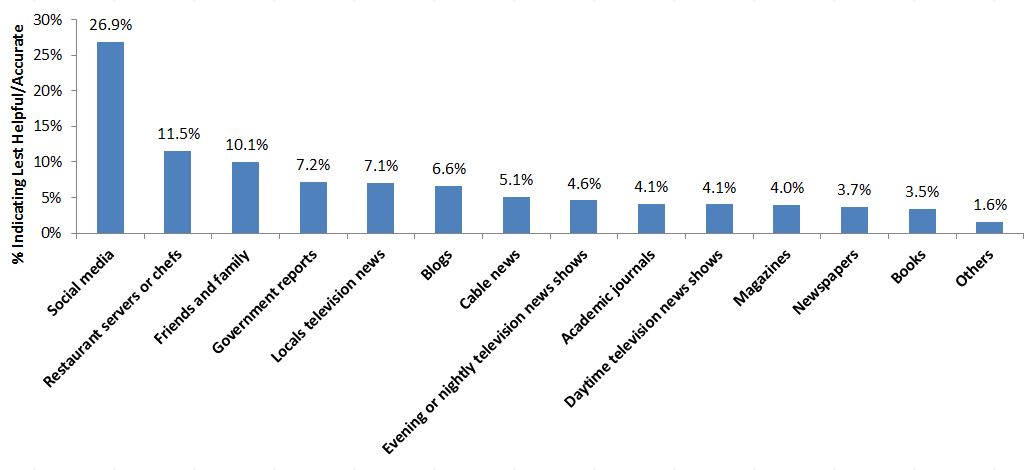

Last, respondents were asked: “Where do you tend to receive the least helpful and inaccurate information about food health and safety issues? (pick one)” The same 14 sources were listed as in the previous question.

By far, social media was the most frequently listed least helpful and inaccurate source of information about food health and safety issues at 27%. 11.5% of participants stated that restaurant servers or chefs were the least helpful and inaccurate source of information. Friends and family was ranked third, with 10.1% of participants. 1.6% of participants selected “other” as their least helpful and inaccurate source of information. Those who stated other, listed examples including “internet news”, “nurses”, “family who think they know”, “Youtube”, and “Packaging”.

To further flesh out the results, the following chart plots the sources according to the percent of respondents indicating the source as most accurate vs. the percent indicating the source as least accurate. Sources on the bottom right of the figure would be more universally seen as most helpful land accurate, where as those on the top left of the figure would be just the opposite.

Restaurant chefs and servers are among least helpful/accurate with local television

news being among the most helpful/accurate. Friends and family are the most polarized group, with roughly equal numbers of consumers listing the source as most accurate and least accurate.