The April 2017 edition of the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) is now out.

A few comments on the regular tracking portion of the survey:

- Willingness-to-pay for all meat products (except deli ham) fell from March to April.

- WTP for pork chops reached the lowest point in the almost four-year history of food.

- Comparing April 2017 to April 2016, only WTP for hamburger is higher than was the case a year ago.

- Awareness of bird flu in the news fell this month and concern for bird flu as a food safety issue experienced the smallest increase of any of the issues studied. Awareness and concern for animal welfare issues rose this month.

We added several new ad-hoc questions to the survey this month.

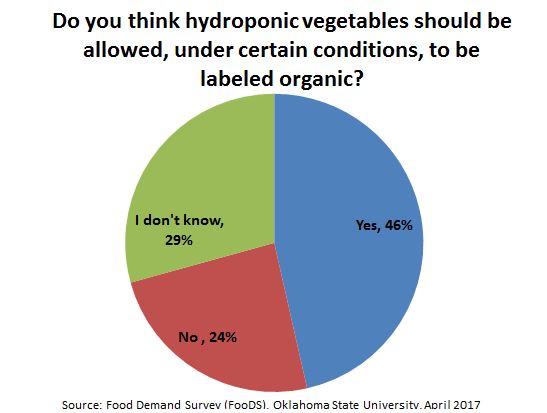

There has been a lot of discussion in the news about whether hydroponics should be able to be labeled organic. We put the question to our participants. They were asked: “Do you think hydroponic vegetables should be allowed, under certain conditions, to be labeled organic? (note: hydroponic vegetables are grown without soil - their roots grow in water with added nutrients and minerals)”

About 46% of participants stated “yes”, hydroponic vegetables should be labeled organic, 24% said “no”, and the remaining 29% said “I don’t know”. It should be noted that due to a glitch in survey administration, only 250 people answered this particular question and as such, the sampling error is higher than usual (it is +/-6% rather than the usual +/- 3%).

A couple weeks ago, I discussed some research we'd conducted studying when consumers don't want to know about certain agricultural production practices. We followed up on this research in this month's edition of FooDs. We were interested in whether people actively sought to avoid information they may find undesirable.

We split people into two equal sized groups. Those in the first group were asked: “On the next page you have two choices of what to see. You can either see a picture of how pregnant hogs are housed on a typical farm or a picture of a blank screen. Which do you prefer?”

To check whether people simply preferred to see a blank screen in general, respondents randomly allocated to the second group were asked a similar question but instead of the option to see a picture of “how pregnant hogs are housed on a typical farm”, they could choose between “a picture of a nature scene or a picture of a blank page.”

Fifty four percent said they wanted to see the picture of how pregnant hogs are housed. By contrast, 46% preferred instead to see a blank page. Thus, slightly less than half the sample actively chose to ignore free information about hog housing. Those who preferred to see the blank screen were less concerned about farm animal welfare as a food safety risk (mean of 3.2 vs. 3.6 on the 5-point scale of concern) and placed less relative importance on animal welfare as a food value (mean of -0.116 vs. -0.097).

Ninety one percent of respondents choose to see the nature scene. Overall, the results suggest just about half the respondents preferred not to know how pregnant hogs are housed.

Finally, we added some questions about food insecurity. I'll discuss these in a separate post.