Since I first started working on the topic of animal welfare, I've had the sense that some (perhaps many?) consumers don't want to know how farm animals are raised. While that observation probably rings intuitively true for many readers, for an economist it sounds strange. Whether we're talking about GMO labeling, nutritional labels, country of origin labels on meat, or labels on cage free eggs, economists typically assume more information can't make a person worse off. Either the consumer uses the information to make a better choice or they ignore it all together.

There is a stream of literature in economics and psychology that is beginning challenge the idea that "more information is better." One simple explanation for the phenomenon could be that consumers, if they know for sure they will continue to consume the same amount of a good, could be better off ignoring information because the information could only lower their satisfaction (perhaps because they'll feel guilty) for doing something they've already committed to doing. In this paper by Linda Thunstrom and co-authors, 58% of consumers making a meal choice chose to ignore free information on caloric content, a finding that Thunstrom calls "strategic self ignorance" arising from guilt avoidance.

Another possible explanation that I've previously published on is that, when people have limited attention, more information on topic A might distract people from a topic B, even though topic B ultimately has a larger impact on the consumers well-being.

It may also be the case that people want to believe certain things. They derive satisfaction from holding onto certain beliefs and will avoid information that challenges them. These ideas and more are discussed by Russell Golman, David Hagmann and George Loewenstein in a nice review paper on what they call "information avoidance" for the Journal of Economic Literature.

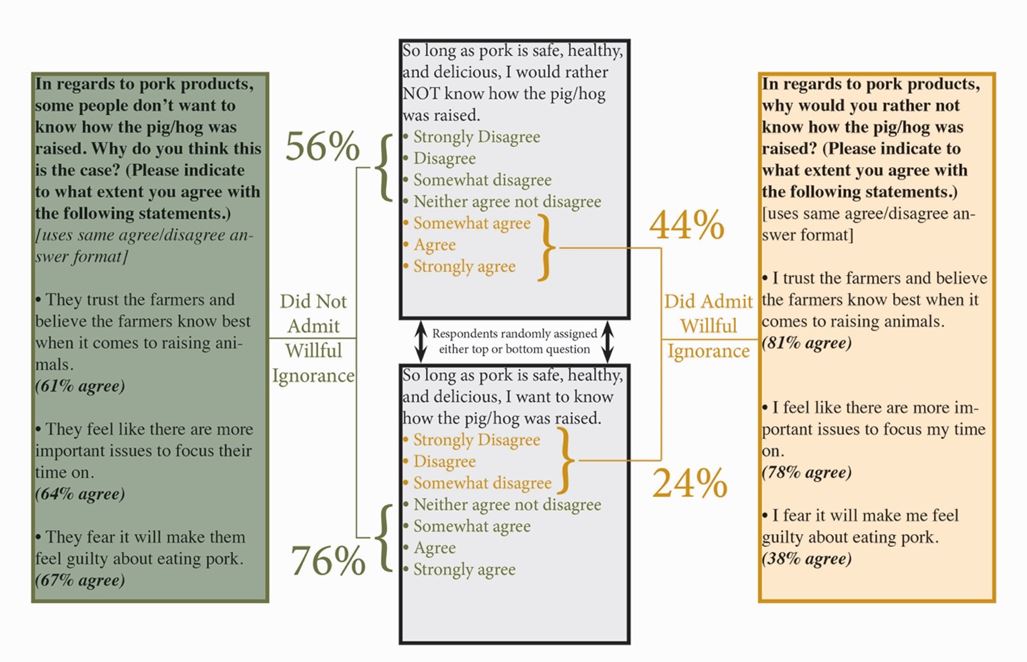

A graduate student in our department, Eryn Bell, has been working with Bailey Norwood to apply some of these concepts to the topic of animal welfare. They conducted a survey of 1,000 Oklahomans and asked them one of the two simple questions shown below. Depending on how the question was asked, from 24% to 44% of respondents self declared that they would rather NOT know how hogs are raised. The primary reasons given for this response were that farmers were trusted (a belief consumers may prefer to hold), that there are more important issues to worry about (limited attention), and guilt aversion.

In the same survey, Bell and Norwood also included a set of questions based on some ideas I suggested. The question gave respondents the option to see a picture of how sows are raised or to simply see a blank screen for a certain period of time. People were divided into three groups that varied how long they had to see the blank screen. The idea was that we could use the waiting time as a "cost", which would allow us to ask: how long are people willing to wait to NOT receive free information? As it turns out, people weren't very sensitive to the waiting time. Nonetheless, regardless of the waiting time, about a third of respondents preferred to see an uninformative blank screen as opposed to a more informative screenshot of sow housing. These findings suggest at least some people, at least some of the time, would prefer not to know.