I’ve noticed several articles in the past few weeks talking about slowing or even falling population growth. This article in the Economist discussed the fact that South Korea’s fertility rate is now below replacement level (i.e., fewer babies are being born than there are parents), and their figure shows the strong negative correlation between income (or GDP) of a country and a country’s fertility rate. The richer we get, it seems the fewer babies we want or need. Then, came this opinion article in the New York Times a couple days ago about the “Chinese Population Crisis,” in which Ross Douthat argues, “Unlike most developed countries, China is growing old without first having grown rich.”

We’ve all probably been adequately exposed to the concerns and problems associated with over-population from the writings of Malthus to Ehrlich’s Population Bomb. Less well appreciated are the benefits and costs associated with a falling population. For one take on the potential concerns, see this 2013 piece by Kevin Kelly entitled the “Underpopulation Bomb.” He states the problem as follows:

“This is a world where every year there is a smaller audience than the year before, a smaller market for your goods or services, fewer workers to choose from, and a ballooning elder population that must be cared for. We’ve never seen this in modern times; our progress has always paralleled rising populations, bigger audiences, larger markets and bigger pools of workers. It’s hard to see how a declining yet aging population functions as an engine for increasing the standard of living every year.”

A smaller population would no doubt produce some benefits. Probably the most obvious benefit is that a smaller population would lessen human’s demands on our environment and natural resources. There is already evidence of this de-materialization. Check out Andrew McAfee’s book More from Less, where he argues that technology has led us past peak demand for many natural resources.

Among the adverse consequences, however, of falling population is likely to be downward pressure on farm incomes. The Malthusian concern implied a large population that was incapable of sufficiently feeding itself. For humanity writ large, this outcome would have been a tragedy. Farmers (or at least land owners), however, would have likely benefited from this dire outcome. More people demanding more food would have driven up food prices, land prices, and farm income. Innovation and productivity growth, fortunately, prevented the hunger problems that would have accompanied a rising population.

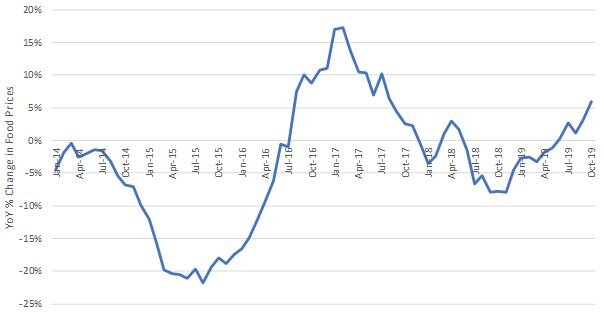

One crude way to see whether population growth is out-pacing the effect of innovation is to look at the long-term trend in food and agricultural prices. Here is a graph I created based on USDA data on three major commodity crop prices over time. The long-term trend is negative, suggesting innovation has outpaced the effects of population and income growth.

Lower prices seems bad for farmers, but if they are able to sell more output using fewer resources, they also benefit (see this paper by Alston for some discussion on the farmer benefits and costs from innovation). Still, it is probably safe to say that farmers and the agricultural sector have largely come to expect a rising world population to support demand growth and offset some of the downward pressure on prices. Population projections suggest that expectation may not hold out into the future.

Indeed, research by my Purdue colleagues Uris Baldos and Tom Hertel suggests the effects of population on crop prices is likely to be much lower than what we’ve experienced in the past. They consider the effect of three factors on crop prices and production: population, income, and innovation. From 1960 to 2006, their findings indicate that the effect of innovation pushed down crop prices more than rising income and population pushed up prices, leading to an overall fall in prices, consistent with the graph above. What do they predict for the future based on expected trends in innovation, population, and income? Falling prices. They predict that, going out to 2050, the price increasing effects of population will be about half what they were from 1960 to 2006. Thus, rather than the Malthusian population bomb, we seem to be heading to a sort of Malthusian inversion.

It’s also important to note that population growth will be unevenly distributed across the world. Data and projections from the United Nations show very different anticipated population trends in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Here is a figure I created based on their data. In 1950, population was 45%, 70%, and 82% lower than it is today in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. By 2010, the UN is projecting population will be 3%, 23%, and 220% higher in high-, middle-, and low-income countries.

The implications for U.S. farmers are many fold. For one, demand growth (at least from population growth) is likely to occur outside this country, highlighting the importance of trade. Within the U.S., rising income, and demand for quality, may play an increasingly important role in supporting farm incomes in the years to come. Finally, flat or declining population, along with innovation, have the potential to have positive environmental outcomes, and it will important to think about appropriate farm policy in light of these trends.