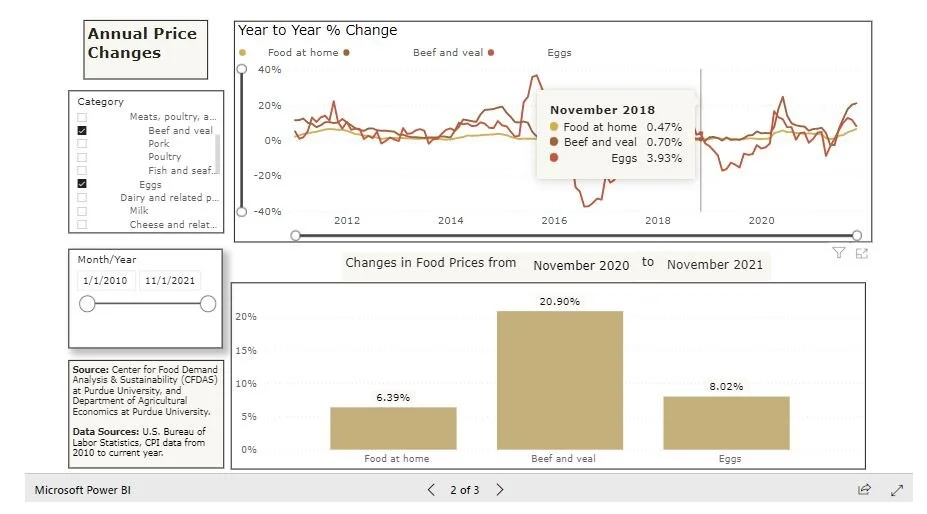

A variety of recent discussions are prompting this post. My last post discussed recent trends in the market for plant-based alternatives, which has been witnessing lower prices and lower consumer expenditures (or equivalently lower total dollar sales) than this time last year. I indicated that the trends indicated a downward shift in demand (i.e., a reduction in consumer willingness-to-pay). Several commenters, however, argued other factors could be at play, but I’m skeptical. At the same time, we’ve been seeing rising overall food prices and rising consumer expenditures on food. For many observers, the co-movement in these variables seems obvious: of course consumers are going to spend more if prices go up. However, this seemingly intuitive logic makes very specific assumptions about the elasticity of consumer demand and magnitudes of concurrent supply and demand shifts. Given the level of back-and-forth on this issue, I thought it might be worthwhile to write a little Econ 101 primer on the relationship between price changes, expenditure changes, and quantity changes. Warning - the rest of the post is fairly pedantic.

Let’s start with a setting in which there is no change in the demand curve (i.e., consumers haven’t changed their collective willingness-to-pays) and price is changing due to some non-consumer related reasons. A well known result (see here for a derivation), taught in many Econ 101 courses, is that the relationship between price and expenditure (or revenue) changes depends on the elasticity of consumer demand (i.e., how sensitive consumers are to price changes around the market equilibrium). If demand is elastic (i.e., quantity consumed is relatively sensitive to price changes), then a rise in price is associated with a fall in consumer expenditures (or seller revenue) – prices and expenditures move in the same direction. Conversely, if demand is inelastic (i.e., quantity consumed is relatively insensitive to price changes), a rise in price will be associated with a fall in consumer expenditures (or seller revenue) – prices and expenditures move in the opposite direction. Based on this simple model, one would take the observations mentioned in the opening paragraphs to conclude that demand for food in general, and for plant-based meat alternatives in particular, is elastic.

However, this conclusion might be misleading because we haven’t yet endeavored to explain why prices may be changing. To address this issue, it is helpful to use a little math, and the basic model I outlined in this paper with Glynn Tonsor.

An approximation to changes in any underlying demand function can be expressed as: Q = n*P +d, where Q is the proportionate change in quantity of the good demanded, P is the proportionate change in price, and n is the own-price elasticity of demand. d is a demand shock representing the proportional change in consumers’ quantity demanded, and it is the magnitude of the horizontal shift in the demand curve expressed relative to the initial equilibrium quantity.

Now, when are talking about relatively small changes, then proportionate changes in consumer expenditures (E) can be expressed as the sum of the proportionate change in price and the proportionate change in quantity: E = P + Q.

So, if we observe a change in prices (P) and expenditures (E), as in the motivating examples about plant-based meat alternatives and overall food price inflation, what can we infer about how consumer demand has changed?

If E = P + Q, then a little algebra also suggests that Q = E – P. Plug our demand curve into this equation and doing little algebra indicates: d = R – P*(1+n).

Ok, so what does this mean? Information from the scanner data company, IRI, indicates sales of meat alternatives (or, equivalently, expenditures on meat alternatives) were down about 8% in November 2021 relative to November 2022. Thus, R=-0.08. The same resource suggests meat alternative prices are down about 2% over this same time period. Thus, P=-0.02. So, what happened to demand?

Using our formula above, d = -0.08+0.02*(1+n). Let’s say demand is very inelastic and n = -0.1 (i.e., a 1% increase in price leads to a 0.1% reduction in quantity demanded by consumers). In this case, d = -0.062. That is, the demand curve shifted inward by 6.2%. This means at the same prices, consumers were willing to buy 6.2% less than they previously were. It also turns out that this means consumers’ willingness-to-pay is 6.2/0.1 = 62% lower today than it was a year ago.

By contrast, let’s say demand is very elastic and n = -2 (i.e., a 1% increase in price leads to a 2% reduction in quantity demanded by consumers). In this case, d = -0.1. That is, the demand curve shifted inward by 10%. This means at the same prices, consumers were willing to buy 10% less than they previously were. It also turns out that this means consumers’ willingness-to-pay is 10/2 = 5% lower today than it was a year ago.

In fact, given the observed price and expenditure changes, there is no plausible demand elasticity that would suggest demand didn’t shift inward.

In a similar fashion, we can also see what happened to supply. We can write a change in a supply function as: Q = e*P + v, where e is the elasticity of supply and v is related to the change in the marginal costs of production. If all we know are price and expenditure changes, using similar logic as above, we can identify the magnitude of the supply shift: v = R - P*(1+e). As before, let’s set R=-0.08 and P=-0.02.

If supply is very inelastic and e = 0.1 (i.e., a 1% increase in price leads to a 0.1% increase in quantity firms supply). In this case, v = -0.058. That is, the supply curve shifted inward by 5.8%. This means at the same prices, firms were willing to supply 5.8% less than they previously were (or marginal costs are 5.8/0.1 = 58% higher today than a year ago).

By contrast, let’s say supply is very elastic and v = 2 (i.e., a 1% increase in price leads to a 2% increase in quantity supplied). In this case, v = -0.02. That is, the supply curve shifted inward by 2%. This means at the same prices, firms were willing to supply 2% less than they previously were (or marginal costs are 2/2 = 1% higher than they were a year ago).