Merriam-Webster defines a foodie as, “a person having an avid interest in the latest food fads.” Wikipedia describes a foodie as “a person who has an ardent or refined interest in food, and who eats food not only out of hunger but also as a hobby.” According to the same source, the word originated in the 1980s and it is apparently some “food insiders” do not like.

Despite the fact the descriptor has been used with increased frequency over the past couple decades, it is not a concept or term I’ve seen analyzed in any depth in academic or industry circles, a phenomenon that is a bit strange given the rising interest in food and emergence of the “food movement.”

To delve into the concept a bit, I added a couple simple questions on a nationwide online survey of over 1,200 U.S. households I conducted about a year ago. I first asked, “Have you previously heard the term: "foodie"?” 87.1% said “yes” and 12.9% said “no.” For the people who said “yes.” I asked, “would you call yourself a “foodie””? 38.2% said “yes.,” 48.3% said “no,” and 13.5% said “I don’t know.” This means out of the entire adult U.S. population, about a third has heard the term “foodie” and considers themselves a “foodie.”

How do these self-declared foodies differ from the rest of the population? To answer this question, I compared the 463 people who had heard the term “foodie” and described themselves as one to the 585 people who had also heard the term but definitively said “no” they were not a foodie. Here are some of the biggest differences:

Foodies are younger. Of people who described themselves as a “foodie”, 35.4% are younger than 35 years of age; of people who said “no” they’re not a foodie, only 21.7% were younger than 35.

Foodies have higher education. Of people who described themselves as a “foodie”, 38% have a college degree compared to only 18.5% of non-foodies.

.Foodies have higher income. Incomes of foodies are about 12% higher on average than non-foodies.

Foodies are more likely to be vegetarian or vegan. 5.8% of foodies said they were vegetarian or vegan compared to only 2.2% of non-foodies.

Foodies are more likely to have children at home. 34.8% of foodies have a child under the age of 12 at home compared to only 16.8% of non-foodies.

Foodies are more likely to be politically liberal and be members of the Democratic party. Of people who described themselves as a “foodie”, 47.3% are Democrats compared to only 38.1% of non-foodies.

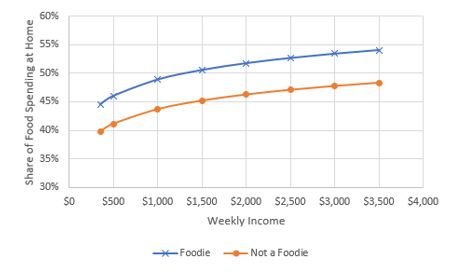

Foodies spend more money on food. Self-declared foodies spend about 45.8% more each week on food at home (i.e., through grocery stores) and about 18.8% more each week on food away from home (i.e., restaurants) than non-foodies.

There were not particularly large differences in region of residence (foodies are a bit more likely to live in the Southern U.S.), gender (foodies are a tab bit more likely to be male), or race (foodies are a bit more likely to be non-white).

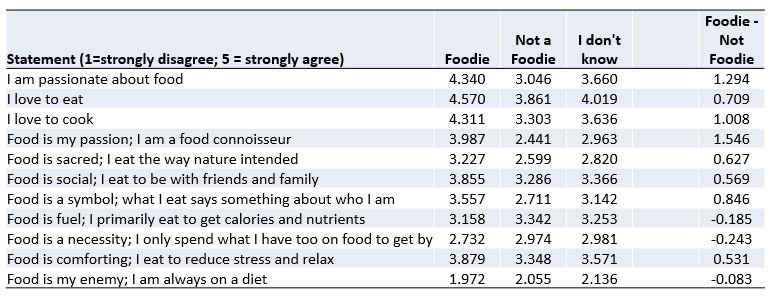

We also asked people the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with various statements about food. Here’s the breakdown showing the mean response of each group on a 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree scale.