Last year an article in The Atlantic began as follows:

“Jayson Lusk’s Thanksgiving tradition, if you could call it that, is to talk with reporters about the prices of Americans’ holiday groceries. ”

Well, it’s that time of year again, so we might as well get into it. I’ll focus on the main course: turkey.

Frustratingly, the Bureau of Labor Statistics stopped reporting a retail turkey price a couple years ago in their monthly releases of data surrounding the Consumer Price Index. So, we have to cobble together insights from other sources.

IRI tracks retail grocery store scanner data. Their data dashboard suggests retail turkey prices have been running about 20% higher than last year; however, for the most recent week of data available (the week ending 10/23), retail turkey prices were “only” 9% higher than the same week last year. For some perspective, as of September (the most recent data available), the BLS reported overall annual rate of food price increase at grocery was 13%.

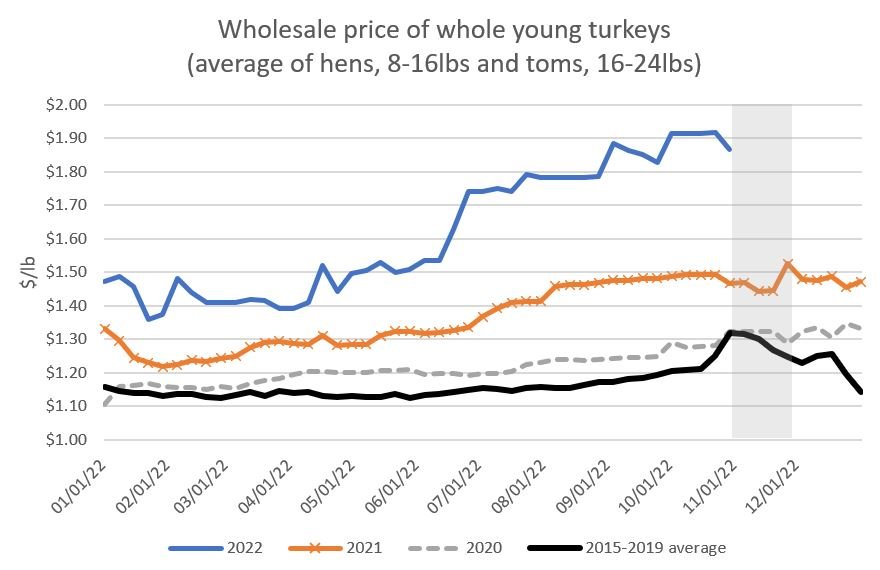

The USDA Agricultural Marketing Service tracks wholesale turkey prices. The figure below shows the trends. At present (last data point is 10/29/2022), wholesale prices for whole fresh turkeys are about $1.87/lb. This is about 21% higher than the same time last year (in 2021) and about 29% higher than two years ago (in 2020).

An interesting feature of the data is that prices tend to fall each year during November (the area shaded in grey). I discussed this back in a post in 2016, where a similar phenomenon was observed for retail prices. Here’s what I wrote then:

“This pattern of price fluctuation might be a bit surprising. Isn’t it the case that demand for turkey is highest in November? If so, shouldn’t a demand increase drive up prices? Yes, but producers also know when demand spikes occur and they can plan production and storage accordingly (this is a fairly highly integrated industry) so that there is ample supply during this time. Additionally, research on this topic has suggested that retailers might use turkeys as so-called “loss leaders”. Knowing that many consumers will be shopping for turkeys, retailers will offer specials and discounts on the item everyone is looking for to get them in the door so that they’ll buy all the other things it takes to make a Thanksgiving meal. ”

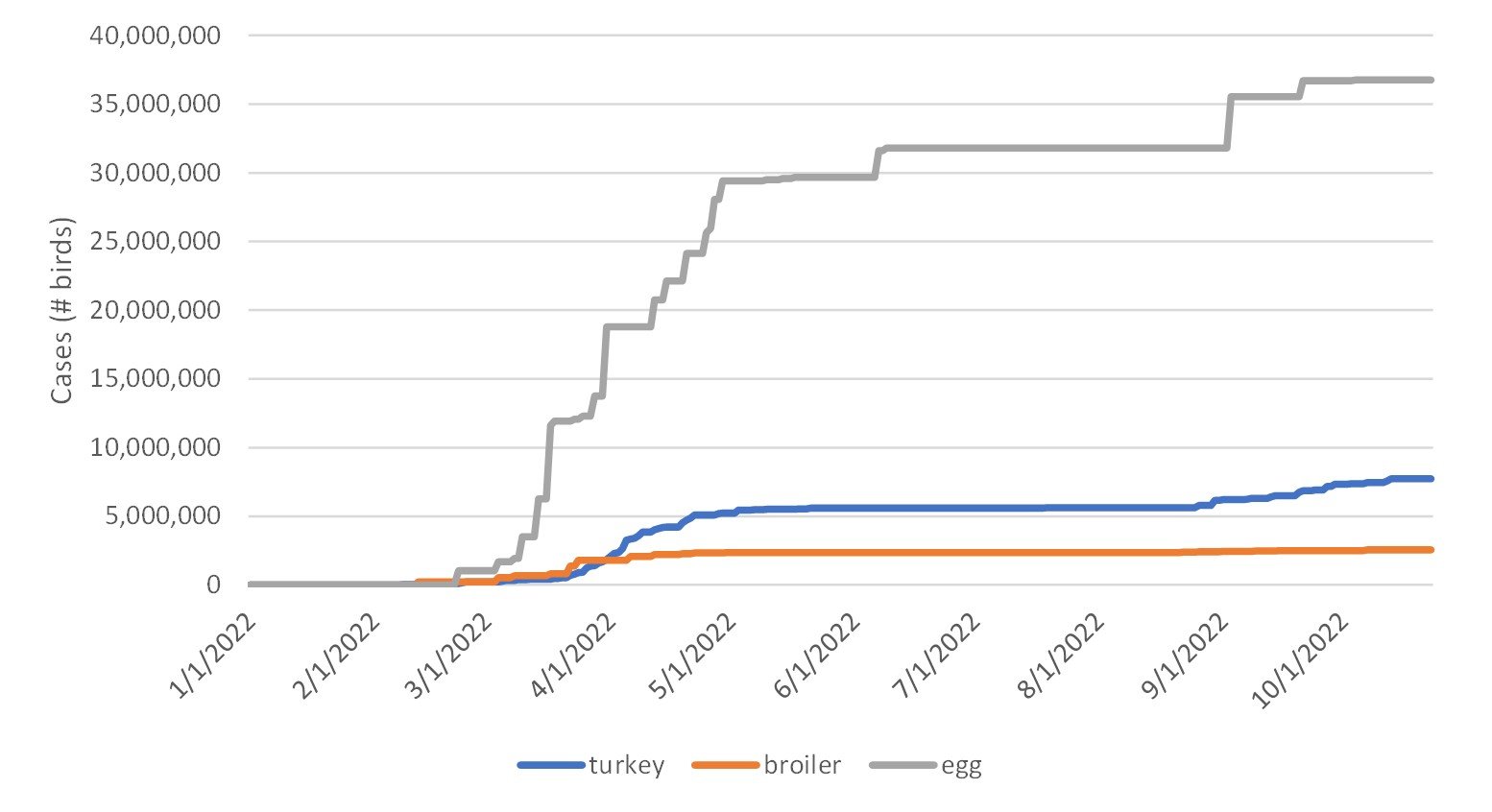

Why are prices higher this year? A potential answer is avian influenza (aka “bird flu”). According to USDA-APHIS data, over 7.7 million turkeys have been affected and killed by the disease this year. The figure below show the cumulative number of avian influenza cases this year for egg laying hens, turkeys, and broiler chickens. Many more egg laying hens have been affected than any other types of birds, but as a percent of total production, turkey has probably been hardest hit.

We’ve lost about 5% of total national turkey production because of avian influenza this year. Indeed, USDA data indicates that slaughter of young turkeys through the 1st nine months of 2021 is down about 7% relative to the same period in 2021. In September 2022, turkey production was down 11.4% related to September 2021. Less turkey is being produced, which means consumers are left competing against each other for a smaller quantity, which drives up prices.

On that front, I want to be clear that we don’t have a turkey shortage. In fact, we rarely have shortages of any food product per se (that’s why baby formula issue was such a newsworthy event - it’s unusual!). Price is the mechanism by which agricultural production gets allocated. If fewer turkeys are produced, prices need to rise to ration the quantity produced to those people who value turkeys most. By contrast, if many extra turkeys are produced than expected, prices would need to fall to induce more consumers into buying them. In that sense, price both is the signal of scarcity/abundance and it is also the mechanism that ensures that all the quantity produced is allocated to consumers.

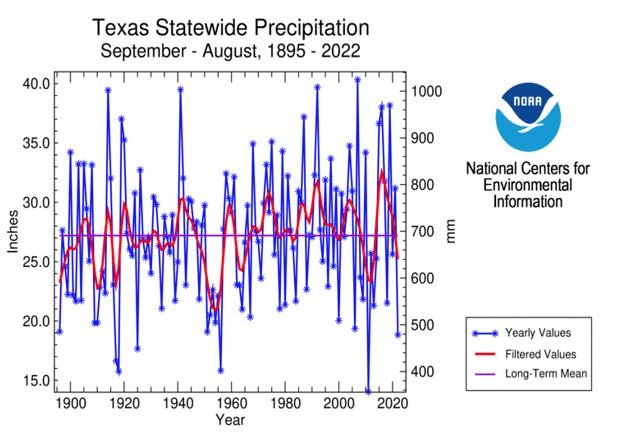

All the other factors driving food prices higher generally are also affecting turkey prices. Corn and soybean (key turkey feedstuffs) are much higher this year than last. Energy prices are higher, affecting costs of transportation, processing, and storage. Wages in the processing and retailing sector are higher too.

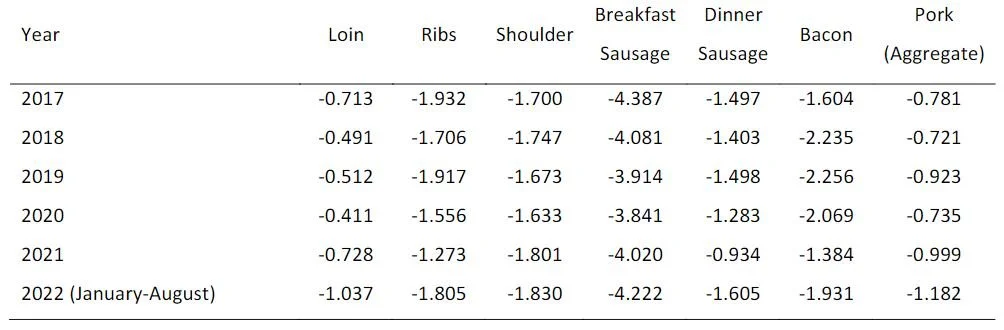

The question on everyone’s mind last year: is this the most expensive Thanksgiving ever? My answer this year is largely the same as last year. Prices in the economy tend to rise over time, so prices are almost always higher this year than last. What we want to know is what is happening to consumer buying power. For that, I’ll direct you to the data dashboard we created with the Center for Food Demand Analysis and Sustainability (CFDAS), where you can see trends in nominal prices, inflation-adjusted prices, and in time-prices (i.e., how many hours one has to work at today’s wage to buy a pound of a given food).

One last point that may be of interest. Per-capita turkey consumption has been on the decline for the past few years. Data from the USDA-ERS shows turkey consumption was 15.3 lbs/person/year in 2021, down from 15.7 lbs in 2020, 15.9 lbs in 2019, 16.2 lbs in 2018, and 16.5 lbs/person/year in 2017. Per-capita turkey consumption fell every year during this period. From 2017 to 2021, per-capita turkey consumption fell over a pound, a 6.9% reduction. Some of this was likely pandemic related. More people worked from home, meaning they weren’t packing or ordering turkey clubs and sandwiches. But, the downward trend started prior to the pandemic. Falling per-capita consumption can sometimes be a results of shifts in cost and supply, but the data seem to suggest this is a downward shift in demand. This downward shift in demand, coupled with higher prices, likely means fewer turkeys on the Thanksgiving table this year.