Earlier this week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released their monthly inflation statistics, and food prices continued their climb.. For example, grocery prices increased 13.5% in August 2022 compared to the prior year in August 2021 (see our data dashboard if you want to do a deeper dive yourself). The question everyone wants to know is: how long will this continue?

Truth is nobody really knows and many economic prognosticators were suggesting overall inflation (the rate of increase in food plus non-food prices) would fall in August, when in fact the pace of price increases slightly increased.

Predicting the future is hard. Nonetheless, I’m going to step out on a limb and make a specific prediction. I’m suggesting one should expect higher beef prices a couple years from now.

Why? Well, drought and higher feed prices across the U.S. are making it difficult for farmers and ranchers to hold on to their breeding stock (i.e., cows and heifers). Here' is Josh Maples at Mississippi State University in his latest newsletter:

“Regionally, cow slaughter in the Southern Plains is much higher than in 2021 where drought has been a major factor. Region 6 consists of Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas and beef cow slaughter in this region is about 30 percent higher year-to-date in 2022 than in 2021. That is more than 150,000 head higher than a year ago in this region. These are very high levels of cow slaughter and even surpass the high slaughter totals seen during the 2011 drought. ”

He goes on to write:

“While increased cow and heifer slaughter totals are contributing to higher beef production this year, the longer-run implications are tighter supplies. The higher slaughter totals imply fewer cows and fewer replacement heifers to produce calves.”

Fewer calves in 2022 and 2023 means there will be fewer cattle and ultimately less beef in 2024 and 2025. If a cow is bred today, it’ll be 9 months till a calf is born. The calf stays with its mama for 6-12 months till weaning. Then, the calf moves to the “stocker” or “background” phase, where it eats grasses and forages for about a year. Finally, most cattle in the U.S. then move into a feedlot for the final three to six months. Put it all together, the decisions being made TODAY to sell cows and heifers will have impacts on retail beef prices TWO to FOUR years from now (check out this nice podcast discussion between James Mitchell and John Anderson at University of Arkansas for more discussion on the issue).

So, two to three-ish years from now, the period of drought and high feed prices we are now experiencing, will lead to less beef being put on the market. This means 2024 and 2025 beef buyers will have to compete against each other for a smaller quantity of beef on the market, driving up prices.

Another reason, we can be semi-confident in this sort of outcome, is that we can look back just a decade ago and see the same thing played out. The figure below shows retail beef prices. Aside from the recent COVID-related wackiness we’ve seen in beef prices, the last time we had a run-up in retail beef price was in the 2014 to 2015 period (the period shaded in grey below).

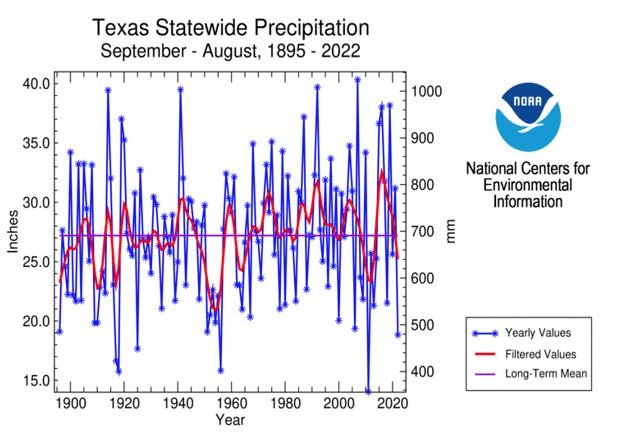

Well, what was happening two to three years prior to to the run-up in beef prices in 2014? You guessed it: drought and high feed prices. I said as much on this blog in March 2014 and again in July 2014 (I suppose that’s one advantage of blogging now for almost a decade!). If you want more proof, check out this graph from the National Centers for Environmental Information showing August-September precipitation in Texas (a major cattle state) over time. As you can see, 2011 had one of the lowest precipitation points on record.

So, write it down: we’ll almost surely see higher retail beef prices in two to three years than we’re seeing today. I’ll be happy if I’m proven wrong.

Another prediction? In a couple years, per-capita beef consumption in the U.S. will fall. As I discussed when this last happened, though, the reason probably won’t be primarily due to higher rates of vegetarianism or heightened concern about animal welfare or the environment or new plant-based substitutes, but the drought-induced liquidation that we are now observing.