Yesterday, Chipotle announced a new advertising campaign called “Real Foodprint.” As the video below shows, a new app reports on a number of environmental metrics (carbon, water, soil) for different Chipotle meals compared to “conventional” ingredients.

Without knowing much about their measurement approach, I am skeptical of Chipotle’s particular claims (for example, much of the research shows avoiding GMOs, hormones, or going organic increases carbon emissions, water use, etc. per unit of food produced). However, I like the overall idea of try trying to provide more objective/quantitative measures on sustainability.

A problem in our current market environment is that various labels (humane, “all natural” non-GM verified, organic, local) are (often incorrectly) interpreted by consumers to imply products are generally safer, healthier, or better for the environment than much of the research would suggest.

Probably one of my favorite opening lines of an academic paper is by Jonathon Schuldt and Norbert Schwarz entitled “The “organic” path to obesity? Organic claims influence calorie judgments and exercise recommendations”:

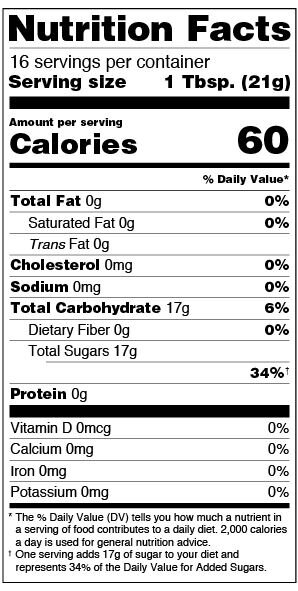

The point isn’t to pick on organic but simply to say that many labels and claims (and, well frankly a lot of marketing) can promote false beliefs (e.g., see this recent paper on redundant labels with Lacey Wilson). One way to try to counteract that is to try to provide more “objective” information. Most food products already carry this sort of information in the form of the Nutrition Facts Panel.

What if this approach was broadened to also include sustainability-related outcomes? Either a “sustainability facts panel” or a broadened “food facts panel.”

Such an approach would be more credible if monitored by a third party (rather than one company’s claims) and communicated in a form that was easily comparable across foods and brands. One hypotheses is that such “sustainability facts panels” might lessen the chance for “false beliefs” and “health halos” to emerge with more nondescript labels ; we currently have research planned to address this very question.

Conceptually, I like the idea of outcome-based reporting and labeling. However, there are a number of empirical challenges. I wrote about some of them back in 2015.

“In principle, it is possible to imagine something like a nutrition facts panel for environmental issues. However, the two are not as analogous as might first appear. First, scientists have a pretty good idea how to measure the fat, carb, and protein contents of food, whereas measuring C02 or deforestation impacts is tricky business with a lot of uncertainty. Moreover, the nutritional content of a processed food is relatively stable regardless of where the raw ingredients came from, which plant or facility was used to manufacture it, how it got to the store, or how you transported and cooked it. None of this would be true for an environmental label, which would require more more extensive (and more costly) monitoring and tracing, and if it is at all accurate, one could have two Wheaties boxes that are nutritionally equivalent but with very different environmental impacts. That may be all the more reason to inform consumers, but the point I’m trying to emphasize here is the much higher cost and greater uncertainty in informing about nutrition vs the environment. ”

As the science on these issues progresses, and as more digital information is collected on farms and transmitted up the supply chain, the likelihood of developing more uniform, credible sustainability facts panels increases.