The March 2017 edition of the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) is now out.

Some items from the regular tracking portion of the survey:

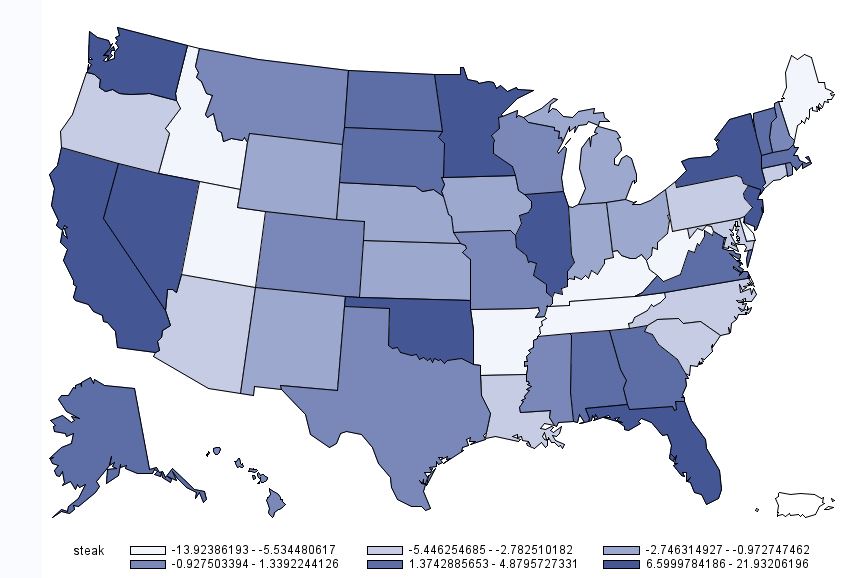

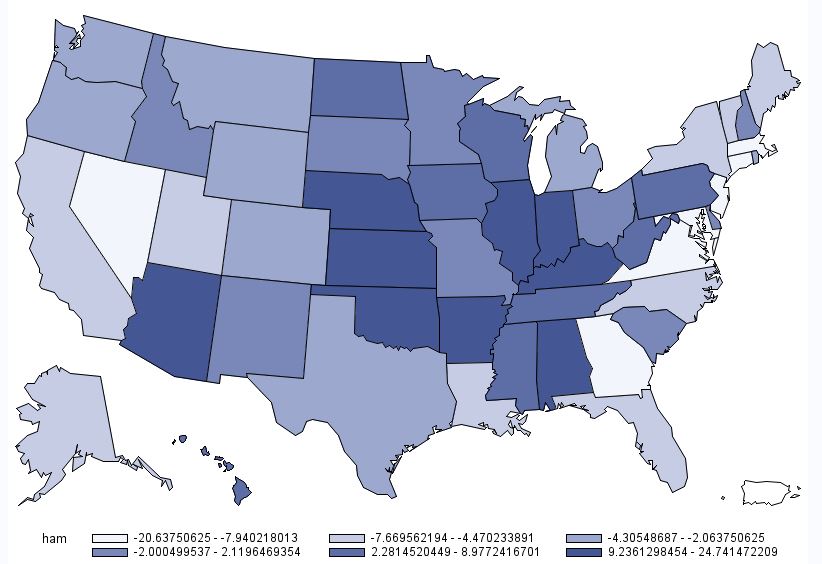

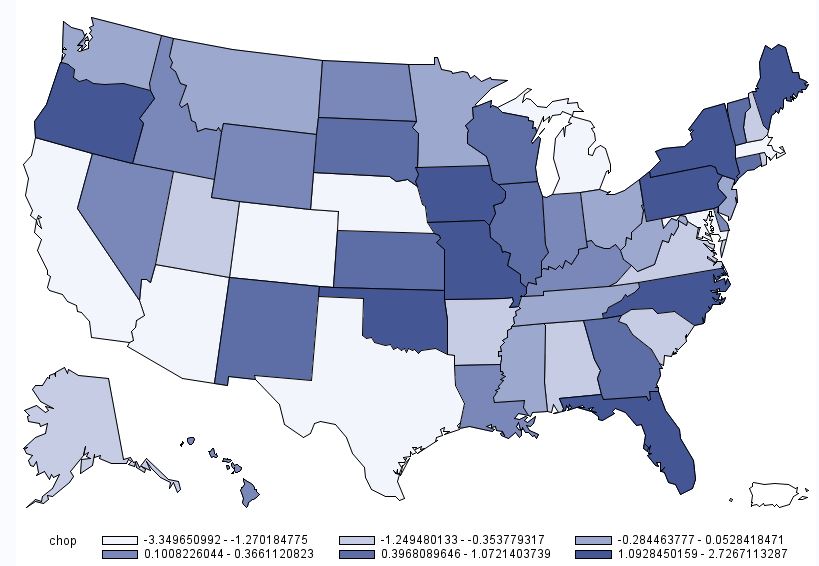

- Willingness-to-pay (WTP) decreased for steak, pork chops, and especially deli ham. WTP increased for chicken breast, hamburger, and chicken wings. WTPs for all meat products are lower than one year ago, except for hamburger.

- Consumers expect higher beef, chicken, and pork prices compared to one month ago. Consumers plan to buy slightly less chicken and beef compared to last month.

- The largest percentage increase in concern was for bird flu and the largest decrease in concern was for farm animal welfare.

Several new ad hoc questions were added to this month’s survey that mainly dealt with knowledge of farm production practices.

Participants were first asked: “Have you ever worked on a farm or ranch?”. About 17% of participants answered “yes.” Participants who answered “yes” were then asked “which of the following best describes the kind of farm you worked on?” Respondents were provided with six options and they could check all that applied.

Of the 17% who said they had worked on a farm, 43% checked “A farm that produces commodity crops (e.g. corn, wheat, soybeans, cotton, or rice)” followed by 40% who checked “A farm that produces commercial livestock (e.g. cattle, swine, or poultry).” “A garden in your backyard” was picked by 38% and “A chicken coop in your backyard” was picked by 23%. 20% checked “other” (and provided responses such as working on a dairy farm or a horse farm or on school farms such as FFA), and 12% checked “A community garden”.

Secondly, participants were asked: "Which of the following animal production industries use added growth hormones?” Over half of participants stated that believed beef, pork, poultry and dairy industries use added growth hormones. Over 75% of participants indicated that they thought that the beef cattle industry uses added growth hormones. Over half of the respondents stated they believe the swine and poultry industries to uses added growth hormones. In reality, the swine and poultry industries do not use any added growth hormones. About 57% of participants stated they believed added growth hormones are used in the dairy industry.

Third, participants were asked: “What percentage of dairy cattle in the U.S. are treated with rBGH?” Overall participants perceive a much greater use of rBGH in dairy cattle than what is actually used. About 20% of participants believe that 50-59% of dairy cattle are treated with rBGH. 5.7% believe that 90- 100% of dairy cattle are treated with rBGH. Only, 10.9% of participants stated that less than 10% of dairy cattle are treated with rBGH. In reality, less than ten percent of all dairy cattle in the U.S. are treated with rBGH.

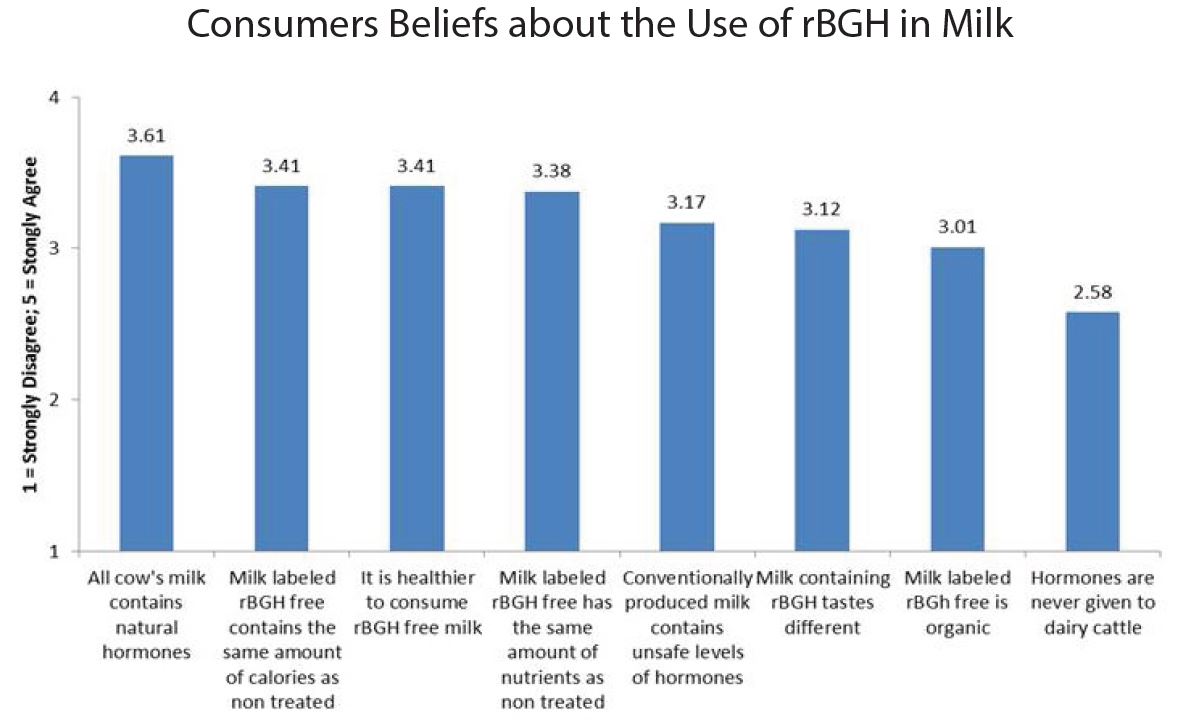

Lastly, participants were asked: “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements?” Individuals responded on a 5-point scale: 1=strongly disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=somewhat agree, 5=strongly agree.

The most common answer for each item was “neither agree nor disagree”, except for the statement all milk contains natural hormones where the most common answer was “somewhat agree”. The statement “all cow’s milk contains natural hormones” was agreed upon most, whereas the statement “hormones are never given to dairy cattle” was agreed upon least.

About 38% of participants answered “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” that it is healthier to consume milk labeled rBGH free. Approximately 30% of participants answered “somewhat agree or “strongly agree” that conventionally produced milk contains unsafe levels of hormones. Only 5.6% of participants selected “strongly disagree” that milk containing rBGH tastes different.