Even though the last farm bill was passed only a couple years ago, I've already started to hear rumblings of lobbying groups jockeying for position in anticipation of the next farm bill which will likely be debated and go into place sometime in 2018 or 2019. Some of the discussion has come about because of the low commodity prices which are leading to lower farm incomes. Discussion is also spurred on by the presidential campaign and talk of the candidates' agricultural advisers. There are also various groups lining up to try to reform farm policy.

Given that backdrop, now's probably as good a time as any to ask: why do farm programs and farm subsidies exist? The question (for this post at least) isn't whether they should they exist, but rather what explains their existence and persistence? Also note I'm not talking about the reasons or justifications farm groups provide for why they say they need subsidies. Rather I'm interested in why they actually exist in the first place. What are the economic and political considerations that lead to the set of farm policies we see?

I touched a bit on this in a paper that was released this summer. Here's a summary (see the paper for the references and more discussion).

A common explanation for agricultural subsidies is a model of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs: the costs of agricultural subsidies go relatively unnoticed by the general public because they are spread across all taxpayers, but the payouts are concentrated among a smaller group of farmers who are well organized and who lobby for the redistributive policies. While this explanation can go part of the way to explaining agricultural subsidies, there are many more considerations and empirical insights offered in the academic literature.

One important fact to note is that farmers aren't subsidized in every country. In fact, farm subsidies mainly exist in relatively rich, relatively urban countries with small numbers of farmers; in poorer, more rural countries with many farmers, subsidies tend to flow in the other direction - from the farms to the cities.

This “puzzle” can be explained by political economy (or "public choice") models. For example, in 1994 Swinnen published a political economy model of farm support to explain why policies often differ markedly across countries, commodities, and time. His model views politicians as utility-maximizing actors who seek election in return for redistribution policies that increase political support. His model leads to a number of interesting predictions, such as (1) politically optimal farm subsidies will increase as agriculture’s share of total economic output falls, and (2) transfers to agriculture will increase if agricultural income falls relative to income outside agriculture.

In a seminal work on the topic in 1987, Bruce Gardner conceptualized agricultural support as arising from an attempt at efficient redistribution (i.e., minimizing the deadweight loss of transfers) given a weight assigned to the rents accruing to agricultural producers, which depends on political and economic characteristics of commodity interest groups. Gardner analyzed how agricultural support varied over time and across agricultural commodities and hypothesized that the weight given to agricultural producers depends on economic factors that convey political power. Groups that have more common economic interests and that are able to reduce the cost of lobbying are likely to garner greater redistribution.

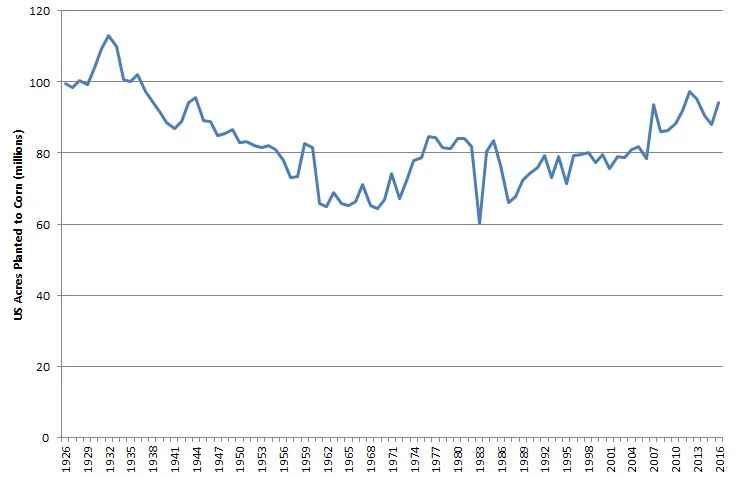

Analyzing data on subsidies paid to 17 farm commodities from 1909 to 1982, Gardner found that redistribution to a given commodity fell (1) as the absolute value of the elasticities of supply and demand for the commodity increased, (2) when the number of producers exceeded one million, (3) the more production a commodity shifted geographically over time, (4) for commodities whose production was more geographically diffuse (rather than concentrated in a given region), (5) as farm income increased, and (6) for commodities that were imported less frequently. Subsequent research by other authors has analyzed the relationship between political donations, lobbying, and congressional voting, and the general finding is that these activities increase subsidies and protection for agricultural groups.

Finally, I'll mention an issue I rarely hear discussed among economists who have studied the political economy of farm support. Often ignored is the influence of another important interest group: voters and food consumers. A growing body of empirical literature has revealed that the US public is surprisingly interventionist when it comes to farm and food policy. As described by economist Bryan Caplan, voters are able to hold onto a variety of antimarket biases because they provide psychological benefits but are unlikely to impose significant costs (at the individual level). Thus, one possible explanation for why inefficient agricultural subsidies exist is that voters elect politicians who favor them. That is, one reason agricultural subsidies exist because a majority of voters want them.