Last week, I traveled quite a bit - from Georgia to Montana and back to Oklahoma. In all three locations, I heard a claim that I hadn't yet heard before. Namely that the low cattle prices we are now observing is a result of the repeal of mandatory country of origin labeling (MCOOL) for meat around the first of this year (note: the repeal came about a result of a series of World Trade Organization rulings against the U.S. policy).

I have to admit to being skeptical of the claim. Agricultural economists have been researching this issue for quite some time (e.g., I have a paper on the topic with John Anderson published more than a decade ago back in 2004). By and large the conclusion from this body of research is that MCOOL has had detrimental effects on beef producers and consumers (e.g., see this recent report prepared for the USDA chief economist by Tonsor, Schroeder, and Parcell). It is true that some consumer research (including my own) reveals consumer interest in the topic and willingness-to-pay premiums for U.S. beef over Canadian or Mexican beef in surveys and experiments; however, most consumers were unaware MCOOL was even in place, and research using actual market data hasn't been able to identify any shifts in retail demand as a result of the policy (a summary of this research is in the aforementioned report).

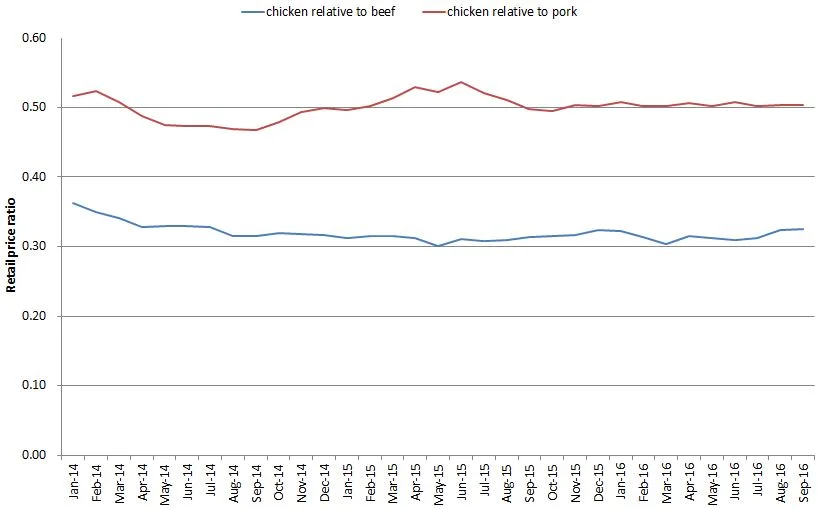

So, let's put my initial skepticism to the side and look at the data. Here is a graph of fed steer prices (blue line) and number of fed steers marketed (red line) over the past several years (these are USDA data from the LMIC and represent the 5-market weekly weighted average including all grades).

The solid black vertical line indicates the point where MCOOL stopped being enforced by the USDA (just prior to January 1, 2016). Looking at cattle prices, one can see how the claim that the repeal of MCOOL caused a drop in cattle prices came about, as the repeal came right after the peak of fed steer prices, after which prices began to fall rather dramatically.

But, is this just a coincidence? Correlation is not always causation.

The red line in the graph shows the number of steers marketed (I plotted the 6 week moving average to smooth out some of the "jumpiness" in the line). There is a strong inverse correlation between the number of fed steers marketed and the price of fed steers. When more cattle are brought to market, prices fall and vice versa. The correlation coefficient is -0.78 over this time period (January 2, 2000 to early November 2016).

What started happening at almost the exact same time MCOOL was repealed? Producers started marketing more cattle. Here's the thing: one can't create a fed steer overnight. The production decisions that led to the increase in fed steers around January 1, 2016 would have had to have been made around two years before. Were producers so prescient that they could anticipate the exact time of the repeal of MCOOL two years prior? Or, rather, was this a "natural" part of the cattle cycle?

As the above graph shows, producers started having many fewer cattle to sell beginning in '08 on into 2012 for a variety of reasons such as drought and high feed prices. These lower cattle numbers led to higher prices, which in turn eventually incentivized producers to retain heifers and add more supply to reap the benefits of higher prices. When did all those extra cattle start hitting the market? It turns out (largely by chance) that it was the same time MCOOL was repealed.

Let's go one step further. Because the supply of fed cattle is relatively fixed in the short run (as production decisions have to be made many months prior), we can use the above data to get a very crude estimate of the demand for fed cattle. Using just the data shown in the above graph, I find that 81% of the variation in (log) live steer prices is explained by changes in the (log) quantity of steers marketed. Estimates suggest that a 1% increase in the (six month moving average of the) number of steers marketed is associated with a 0.5% decline in live steer prices.

Since the 1st of the year there has been a roughly 120% increase in the number of steers marketed (from an average of around 14,600 head/week just prior to the first of the year to an average of around 32,500 head today), and our simple demand model would suggest that this would lead to a 120*0.5=60% decline in cattle prices. Yet, cattle prices have "only" declined about 25% (from around $133/cwt at the first of the year to around $100/cwt now). So what? Well, if MCOOL was the cause of the reduction in cattle prices, we would have expected an even larger fall in cattle prices than our simple demand model predicted, but instead, we're actually seeing a smaller fall than expected.

Now, let's address one possible criticism of the above discussion. What if the rise in fed steers marketed in the graph above is because of cattle flowing into the US from Canada and Mexico once MCOOL was repealed? Here is data on imports of cattle from Canada to the US (again from LMIC).

There was a fall and then a larger uptick in the number of cattle imported from Canada to the US right after MCOOL, but nothing out of the ordinary from the typical fluctuations in the three years prior. For example, the "spike" in total imports (slaughter cows + fed cattle + feeder cattle) around May of 2016 is at least 5,000 head smaller than the five previous spikes that occurred when MCOOL was in place.

Even if I take the roughly 5,000 extra imports of fed cattle that came in from Canada after MCOOL from January 1, 2016 to the middle of May, and assumed even than 75% were steers, this would represent only 13% of the number of steers in the 5-market dataset sold to packers. At most, this would cause a 13*0.5 = 6.5% decline in U.S. fed cattle prices according to my simple demand model. This is nowhere near the 25% decline actually observed since the 1st of the year. Moreover, look at what happened to cattle imports during this summer. They fell. They fell at a time when U.S. cattle prices were falling. So, it can't be that extra Canadian imports were the cause of falling U.S. prices during mid summer.

In summary: while it is conceptually possible that the repeal of MCOOL could adversely affect U.S. cattle prices, any actual effect appears to be quite small (if there is any effect at all). The fact that cattle prices fell immediately after the repeal of MCOOL appears to be a coincidence. The falling prices seem more to do with "normal" changes in supply resulting from the cattle cycle than anything to do with MCOOL.