As I've discussed in the past, I've been measuring consumers "food values" in the monthly Food Demand Survey (FooDS) for the past four years. The way this works is that a list of 12 items is presented to respondents and they are asked which are most and which are least important when buying food. Respondents have to click and drag four of the items into a "most important" box and also put four in a "least important" box, leaving four in neither box (for exact question wording see page 7 of this document).

The advantage of this questioning approach is that it requires a tradeoff - respondents can't say all issues are important and they have to indicate some food values as least important. To create a scale of importance, I simply calculate the percent of times an issue is placed in the most important box and subtract it from the percent of times it is in the least important box, creating a measure that ranges from 100% to -100%.

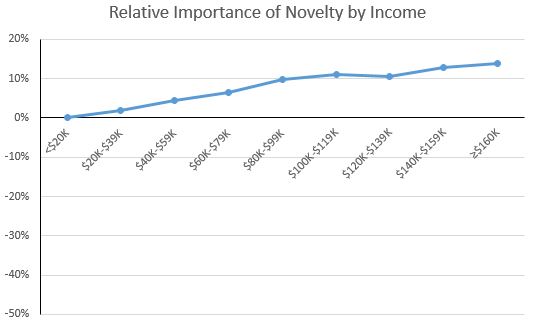

Month in and month out, we consistently find that taste, safety, nutrition, and price are the four most important food values and environment, origin, fairness, and especially novelty are the least important. Issues like appearance, naturalness, animal welfare, and convenience fall in the middle.

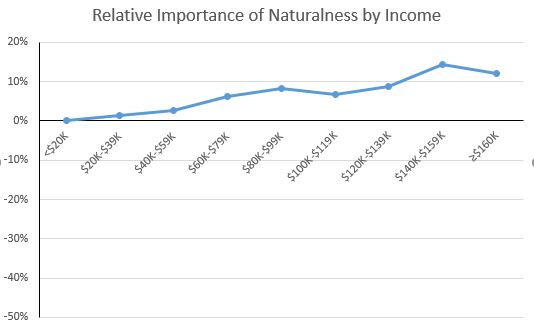

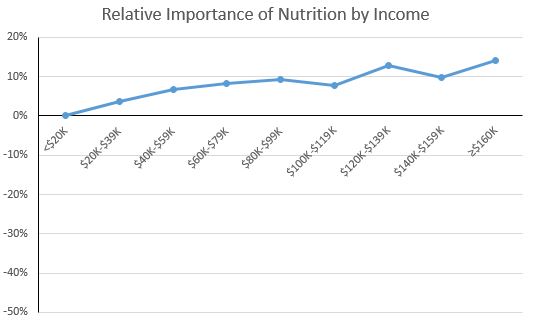

While the above rankings of values are true on average, it is useful to ask: how do food values differ across consumers with different incomes? This question is important because not all consumers have the same preferences, and the people with the ability and connections to affect public policy (and grocery store bottom lines) may give priority to food issues that are less relevant to people in the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum.

To address this issue, I used some statistical analysis to control for differences in age, gender, education, etc. and then compare how people in different income categories rate each food value. For ease of comparison, I always set the food value of people lowest income category (less than $20,000 in annual household income) at zero and compare how much higher or lower (again on the -100% to +100% scale) people in other income categories are relative to consumers in the lowest category.

Food Values Relatively More Important to the Poor than the Rich

There were three food values for which importance tended to decline with income: price, safety, and taste. The big one is price.