“How would it look to apply the principles of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to food management?”

That's the opening sentence by Ellyn Satter in a 2007 article in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. She writes:

“Abraham Maslow arranged basic needs in order of sequential importance to the individual and taught that needs at each level must be satisfied before the individual can become aware of and address the next level of need. From the foundation through the apex on Maslow’s pyramid-shaped Hierarchy of Needs, they are: (1) physiological needs: air, water, food, shelter, sleep, sex; (2) safety, security and order; (3) social affection: love and belongingness; (4) esteem, status: self-esteem and esteem by others; and (5) self-actualization: being all the individual can be.”

She then proposes (without any data or evidence I might add), the following hierarchy of food needs.

Satter argues this hierarchy is important to understand for nutrition educators who should:

“join with individuals right where they are. For those whose most pressing concern is getting

enough to eat, help them choose dependably filling and satisfying food. Address energy inadequacy by endorsing adding fat—butter, oil, or salad dressing—to vegetables and grains and using whole milk. Point out the nutritional value of preferred food items, and suggest additional low-cost food items that are both energy dense and nutritious. But avoid prioritizing food selection based nutritional considerations alone. Doing so is realistic only for people who are functioning at the apex of Satter’s Hierarchy of Food Needs.”

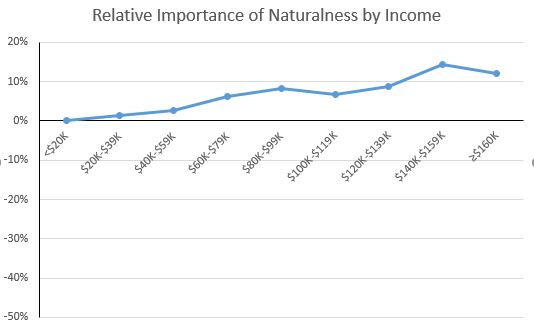

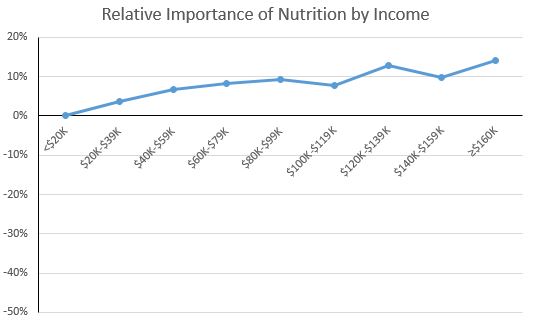

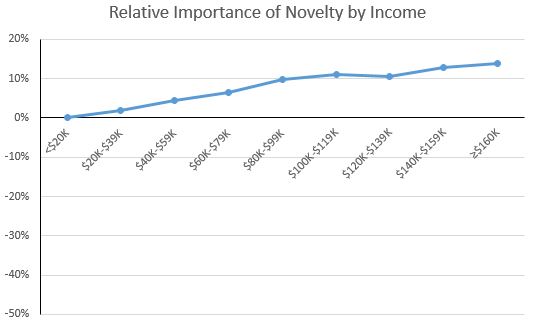

To what extent is this "model" true? A few weeks ago, I compared the food values for the rich and poor, which provided some support. But, even that data suggests taste, safety, price, and nutrition are top four food values (out of 12 total values) for both low and high income. The ranking for high income is taste, nutrition, safety, and price and for low income is price, taste, safety, and nutrition; factors like fairness, novelty, and origin were ranked last for both high and low income groups. It would be interesting to see studies comparing income elasticities of demand for foods that fit the above criteria. However, the above model doesn't necessarily suggest income is the main driver - only that one has to meet a "lower" need, via whatever means, before another "higher" need is met.