Last week, Nature published this piece on a massive study conducted by Chinese agricultural researchers. Accompanying the piece was a summary/editorial describing the study:

“Running from 2005 to 2015, the project first assessed how factors including irrigation, plant density and sowing depth affected agricultural productivity. It used the information to guide and spread best practice across several regions: for example, recommending that rice in southern China be sown in 20 holes densely packed in a square metre, rather than the much lower densities farmers were accustomed to using.

The results speak for themselves: maize (corn), rice and wheat output grew by some 11% over that decade, whereas the use of damaging and expensive fertilizers decreased by between 15% and 18%, depending on the crop. Farmers spent less money on their land and earned more from it — and they continue to do so.”

The project appears to have created substantial economic benefits. The authors of the study write:

“Direct profit, calculated from increased grain output and reduced nitrogen fertilizer use, was US$12.2 billion (Table 1), which does not include relevant environmental benefits associated with reductions in reactive nitrogen losses and in GHG emissions. On the basis of the rough estimates, the cost:benefit ratio would be 1:226. ”

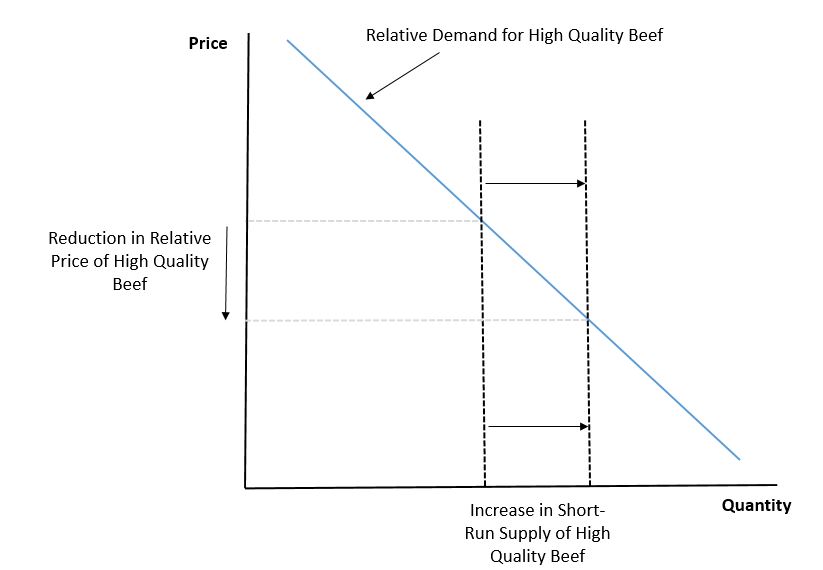

The cost-benefit ratio is in some ways over- and in other ways under-estimated. The benefits are over-estimated in the sense that it does not appear it takes into consideration the fact that greater grain production will dampen prices (it is also unclear how the benefits and costs are discounted or not over time). The benefits are under-estimated because they do not include any of the environmental improvements.

It is useful to contrast these findings with the rather large research on the value of agricultural R&D and extension investments in the U.S. Jin and Huffman calculated the rate of return on spending on agricultural extension in the U.S. at 100%. More broadly, Julian Alston gave the fellow's address at this this year's AAEA meetings on precisely this topic, and his remarks were recently published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics. He writes:

“Our estimates (Alston et al. 2010a, 2011) indicate that U.S. federal and state government expenditure on agricultural research and extension generates benefit-cost ratios of at least 10:1 (more likely 20:1 or 30:1)—evidence of a serious underinvestment. Pardey and Beddow (2017), echoing Pardey, Alston, and Chan-Kang (2013), suggested that a reasonable first step would be to double U.S. public investment in agricultural R&D—an increase of, say, $4 billion over recent annual expenditures. A conservatively low benefit-cost ratio of 10:1 implies that having failed to spend that additional $4 billion per year on public agricultural R&D imposes a net social cost of $36 billion per year”

Given the lower level of development in China, it is certainly possible to imagine that the rate of return on investments in agricultural research and extension being higher than is the case in the U.S. But, can the benefit cost ration really be 10 times higher in China than the U.S. (226:1 vs. 20:1)? One interesting thing about Chinese study in Nature is that, if I read correctly, it didn't entail development of any new genetics, pesticides, etc; rather it seemed to largely entail the application of previously developed "science" and practices to the particular geographies in question, and as such, the costs might have been much lower than in situations where new technologies are being created.

In a sense, the shows an enormously high value to "better information." This contrasts with perspectives such as this one by David Pannell, who argues that better technologies are much more impactful than "better information." One way to reconcile this seeming paradox is that that the "information" conveyed to the Chinese farmers was to use better technologies and practices that were already known to exist. Here in the developed world, the knowledge/technologies are likely already more widely dispersed.

I'll end with this quote from Alston's paper, who articulated the value of increased productivity in a createive way:

“Clearly agricultural productivity growth is enormously valuable. Of the actual farm output in 2007, worth about $330 billion, only one-third (i.e., 100/280 = 0.36) or about $118 billion could be accounted for by conventional inputs using 1949 technology, holding productivity constant. The remaining two-thirds (i.e., 180/280 = 0.64) or about $212 billion in that year alone, is attributable to the factors that gave rise to a 180% increase in productivity since 1949—including improvements in infrastructure and inputs (if not captured already in the indexes), as well as new technology, developed and adopted as a result of agricultural research and extension, and other sources of innovations.”