A couple months ago, I was asked to give a talk at a TEDx event put on at Purdue University. The video is finally available online. I talked about the evolution of animal agriculture and the impacts on food prices and animal welfare, and I ended with my proposal for an animal welfare market, which I've previously written about here and here.

Blog

Pork: The Other Red Meat

Remember the long running campaign by the Pork Board?

The campaign pitching pork as the other white meat made sense at a time when there was rising concern about fat content and red meat consumption and increased competition from chicken. But, times have changed.

One of the changes has come about from scientific developments. As it turns out, pork color is a good indicator of eating quality, and in blind taste tests, consumers prefer redder pork to whiter pork. Do consumers know this? Could a quality labeling system help coordinate the pork supply chain and better align production with consumers' eating expectations?

These were the questions that led to this paper just released by the journal Food Policy that I co-authored with Glynn Tonsor, Ted Schroeder, and Dermot Hayes with funding by the National Pork Board (a longer report of the results is here).

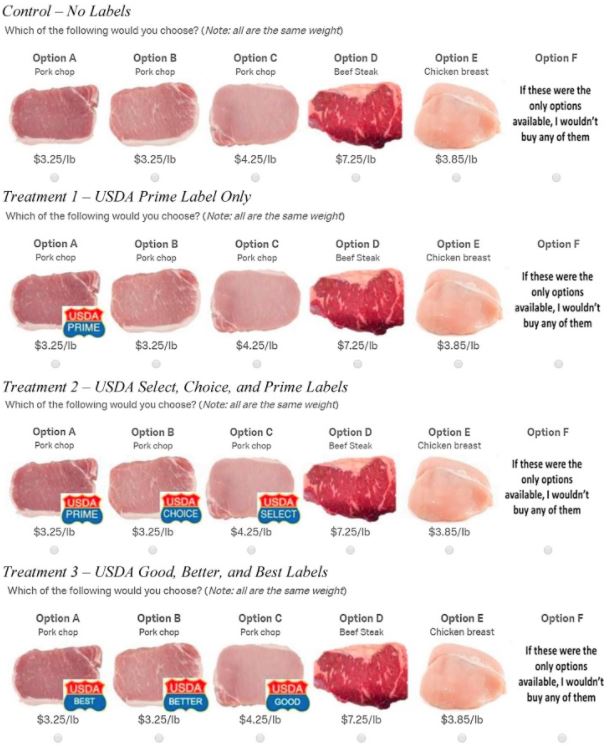

We surveyed about 2,000 consumers for the analysis reported in the Food Policy paper. We were mainly interested in how consumers' choices between pork (and other meat) products varied with the color of the pork and whether and which kinds of labels were present. Consumers were randomly assigned to a control (with no labels) or one of several treatment groups that utilized different labeling systems. Below shows a particular choice question used in the various treatments.

We use the choices consumers made in these treatments to back out consumers' willingness-to-pay, but even more importantly, the probability a consumer buys any type of pork and the expected revenue from pork. For the economists out there, I'll note that we also have some methodological innovation. Rather than just looking at the probability of buying a type of pork at a given set of prices, we also invert the equations to look at the equilibrium price of pork at a given quantity of different types of pork (this is important because in the short run, pork producers can't easily produce a larger amount of higher quality pork).

So, what did we find?

We find:

“In the absence of a cue in the “no labels” control, on average, participants do not differentiate among the three quality levels [or pork colors]. There is no significant difference in average WTP [willingness-to-pay] for the three different colored chops. This is consistent with industry interest in adding quality labels to facilitate further separation of pork quality by consumers. The introduction of a single Prime label for the highest quality chop in Treatment 1 results in a significant increase in the WTP for the chop that would carry the highest quality grade; however, there is a significant reduction in WTP for the lower quality chops that did not carry labels in this treatment. ... When all pork products have grade labels, there is a significant premium for higher vs. lower quality pork and total pork sales rise, as do expected revenues. This can be seen in [the figure] as the mean WTP estimates for all pork qualities lie above those in the control condition with no labels.”

We go on to show there is significant heterogeneity in consumer preferences. We find that 28% to 40%, depending on the labeling condition, of consumers prefer white pork to red pork.

From the conclusions:

“The choice experiment data analysis suggests that a USDA grade using Prime, Choice, and Select or Good, Better, Best labels would be most likely to increase expected pork revenue and the probability of purchasing pork. Additional important opportunities are present within this strategy. Foremost is that even with quality labels on the pork chops, a significant fraction of consumers preferred lower quality than Prime even when the three quality products were priced the same. Such consumers either do not understand the quality grade rankings of Prime, Choice, and Select (though results were similar for Best, Better, Good, which should be less prone to confusion), or this group of consumers were ignoring the quality grade labels and relying on product color to influence their choices. A possible response would be to segment consumers and to use the grading system only on those consumers who prefer red chops. Segmentation could be done by exploring preferences across states, institutions, income categories, ethnicity, and by export market. Despite the possibility for segmentation, however, we show, that if all qualities are present, only labeling the highest quality is likely to reduce total pork sales and revenue”

As this piece in the Federal Register indicates, the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service is seeking public comment on the usefulness of such a labeling system. Maybe one day in the future you will see new pork quality grade labels in the grocery store.

An unplanned shock to beef quality supply

In economics, it's tough to separate correlation from causation because the world is a messy place with lots of things changing at the same time. As a result, empirical economists are always on the lookout for natural experiments, or situations where there was some random, unanticipated "shock" to the market that can help us get closer to an experimental setting, where we know a change in X was not due to a change in Y.

I was reading through the latest edition of Meatingplace magazine, and was surprised to see a story about an event that provides precisely the sort of unplanned "shock" that we are always looking for. In particular, about eight years, ago, the USDA started using cameras (rather than people) to determine meat quality. The two main quality grades are Choice (more marbled (or fattier), higher quality) and Select (leaner, lower quality).

Apparently in June 2017, the USDA issued an update to USDA's camera grading system that "appeared to inaccurately assess the degree of marbling on some carcasses - allegedly grading some Choice that should have been Select." The USDA issued a new update to the cameras in October in 2017 to correct the problem. One analysis, quoted in the article, estimates that about 12,000 cattle were inadvertently graded Choice rather than Select (a 2.4% increase according to the article, if I'm reading it right).

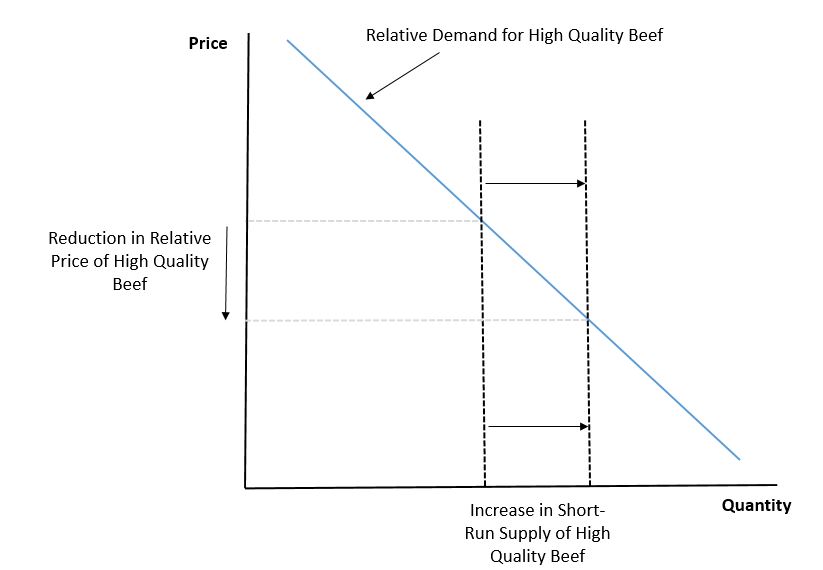

So, we have an unplanned, unanticipated "shock" to the beef quality market that shifted the supply of high quality meat and reduced the supply of lower quality meat. This is illustrated by the two vertical lines in the figure (the lines are vertical because the supply is fixed in the short-run: you can't take Choice carcass and turn it into a Select one once the animal has been removed from feed). If demand curve slopes downward, then this unanticipated increase in supply of Choice (and reduction in Select) quantity, should reduce the price premium for Choice over Select. And in-fact, because the shock to supply is completely exogenous (it had nothing to do with demand but with a camera update), we should be able to use the natural experiment to estimate the slope of the relative demand curve for high quality beef (or the so-called elasticity of demand).

Here is data from the USDA on the difference in price between Choice and Select beef, or the so-called Choice-to-Select spread, over the time period of interest (in particular, this is the difference in boxed beef cutout values measured in dollars per hundredweight - or cents per pound).

Just as one would expect, the increase supply of Choice relative to Select led to a reduction in the price premium charged for Choice relative to Select. Of course, these raw data might be misleading - what if there is a seasonal pattern in which the Choice-to-Select spread falls every year from June to October? To address this concern, I downloaded the last 10 years of data on the Choice-to-Select spread and found that the observed Choice-to-Select spread from mid June to late October in 2017 was $4.34/cwt lower than would be expected even after controlling for seasonality (month of the year), year, and a time trend. This works out to about a 31% lower Choice-to-Select spread than would have expected during this time had it not been for the grading camera update (assuming there aren't other confounds I'm not controlling for).

So, good news, it appears, the demand curves do indeed slope downward. We can also go further if we take the aforementioned 2.4% change in quantity at face value that came from the Meatingplace article. The price flexibility of demand (this is roughly the inverse of the elasticity of demand) for Choice (relative to Select) is given by the percent change in price over quantity, or -31%/2.4% = -12.9%. So for every 1% increase in the quantity of Choice vs. Select supplied, there is a 12.9% reduction in the Choice-to-Select price spread.

Factors Affecting Beef Demand

Glynn Tonsor, Ted Schroeder, and I recent completed a report for the Cattlemen's Beef Board on the factors influencing beef demand.

One of the key factors that emerges from the analysis of the USDA price/quantity data is that beef demand appears to have become less sensitive to price-related factors. In econ-lingo, beef demand has become more inelastic. Moreover, changes in pork and poultry prices have fairly small impacts on beef demand.

As a result, we focused on several potential non-price demand determinants. We find that emerging stories about climate change have adversely affected beef demand, but at the same time increased media focus on taste and flavor have more than compensated for those effects, pulling up demand since 2012.

We also look at trends from the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) and how they relate to consumers' preferences and beliefs. Here are some graphs on the relationship between a variety of factors and steak demand.

Here is the same but for ground beef demand.

Increases in income clearly increase steak demand, but ground beef is demanded similarly by all income categories. Some of the biggest determinants of beef demand are "food values". Here's what we have to say about how to interpret those results.

“While it may not be initially obvious, results in figure 4.5 [showing the relationship between steak demand and food values] can be interpreted as providing evidence about people’s beliefs about (or perceptions of) steak. Suppose an individual highly values taste. Figure 4.5 shows that such an individual will tend to choose more steak. As a result, it must be that steak is perceived to be highly tasty. By this line of reasoning, figure 4.5 suggests that consumers, on average, perceive steak to be convenient, tasty, attractive, and novel but they also perceive steak to be poor for animal welfare, nutrition, and environment while also being expensive. ”

There's a lot more in the report.

Don't Want to Eat Pink Slime? Would You Even Know?

It's hard to believe it's been almost five years since the finely textured beef (aka "pink slime") scandal broke. To briefly re-cap, by 2012 it had become an industry standard to include finely textured beef with other beef trimmings to make ground beef. The process enabled food processors to add value, cut down on waste, and increased the leanness of ground beef in an affordable manner. But, a series of news stories broke, which caused public backlash against the process, and ultimately led to the closure of several plants that produced finely textured beef. In 2013, I wrote about my visit to BPI, one of the largest producers of lean finely textured beef (this summer, ABC settled a multi-million dollar lawsuit brought by BPI regarding ABC's coverage of the issue). I devoted a whole chapter of my 2016 book, Unnaturally Delicious, to the issue. I'll also note, for some aspiring journalist out there, that I can imagine a highly compelling a book-length treatment of the saga.

Back to the heart of the story, must of the public backlash presumably came about because the public was worried about taste or safety of ground beef made with finely textured beef. In the monthly Food Demand Survey (FooDS), we've been running for almost five years, we ask about perceptions of the safety of "pink slime" and of "lean finely textured beef". The data suggests neither are top safety concerns. The most common answer is that people are "neither concerned nor unconcerned" about the safety of these issues (for lean finely textured beef, the average response is actually in the direction of "somewhat unconcerned").

Well, what about taste? People may think "pink slime" tastes bad, but what would happen in a blind taste test? Along with several of my former econ and meat science colleagues at Oklahoma State University (Molly Depue, Morgan Neilson, Gretchen Mafi, Bailey Norwood, Ranjith Ramanathan, and Deb VanOverbek), we conducted a study to find out. The results were just published in PLoS ONE. Here's what we found.

“Over 200 untrained subjects participated in a sensory analysis in which they tasted one ground beef sample with no finely textured beef, another with 15% finely textured beef (by weight), and another with more than 15%. Beef with 15% finely textured beef has an improved juiciness (p < 0.01) and tenderness (p < 0.01) quality. However, subjects rate the flavor-liking and overall likeability the same regardless of the finely textured beef content. Moreover, when the three beef types are consumed as part of a slider (small hamburger), subjects are indifferent to the level of finely textured beef.”

So, a burger made with 15% finely textured beef is as tasty or tastier than a burger without finely textured beef. If people knew this, would it have changed their reaction to the Jamie Oliver show or the 2012 ABC News stories?