With all the news about Beyond Meat’s stock price and the rolling out of the Impossible Burger at Burger King, there has been a lot of speculation about how consumers might response and about the ultimate size of this market. In a new paper with Ellen Van Loo and Vincenzina Caputo, I’m pleased to bring some hard data to the these debates.

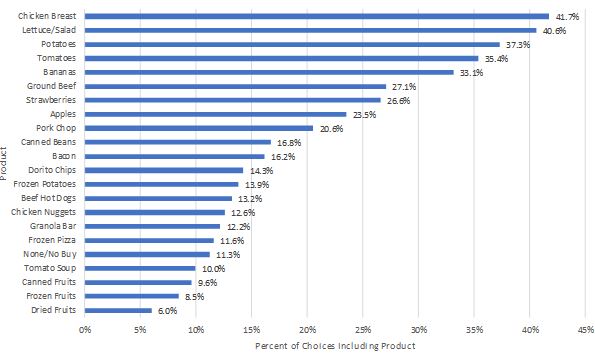

What did we do? We surveyed about 1,800 U.S. food consumers earlier this year and asked them to make a number of simulated shopping choices. In each choice, consumers had five options: conventional farm-raised beef, a plant-based burger made with pea protein (i.e., Beyond Meat), a plant-based burger made with animal-like protein (i.e., Impossible Foods), labgrown meat (i.e., Memphis meats), or they could choose not to buy any of the products (i.e., “none”). Respondents were randomly allocated to different treatments that varied the use of brand names (present/absent) and the information that was provided (none, environment information, or technology information). Here is an example of one of the choices consumers were given (in the treatment that included brands).

So, what did we find? Here is the abstract:

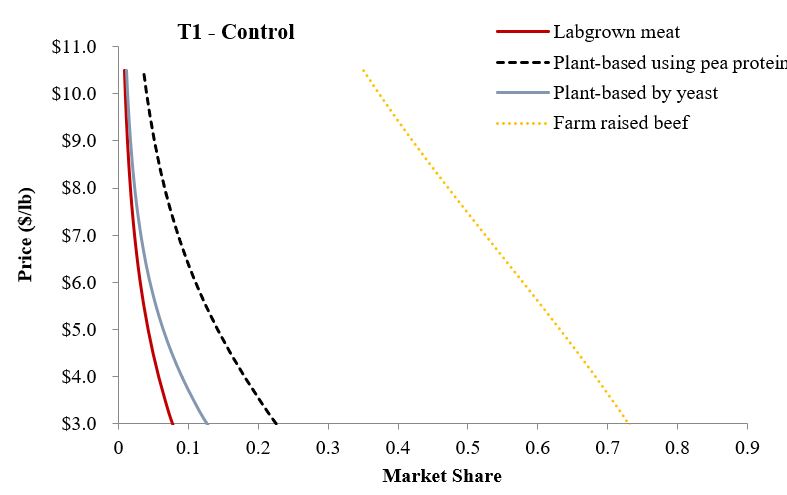

“Despite rising interest in innovative non-animal-based protein sources, there remains a lack of information about consumer demand for these new foods and their ultimate market potential. This study reports the results of a nationwide survey of more than 1,800 U.S. consumers who completed a choice experiment in which they selected among conventional beef and three alternative meat products (lab-based, plant-based with pea protein, and plant-based with animal-like protein) at different prices. Respondents were randomly allocated to treatments that varied the presence/absence of brands and information about the competing alternatives. Results from mixed logit models indicate that, holding prices constant and conditional on choosing a food product, 72% chose farm raised beef, 16% plant-based (pea protein) meat alternative, 7% plant-based (animal-like protein) meat alternative, and 5% labgrown meat. Adding brand names (Certified Angus Beef, Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods, and Memphis Meats) actually increased the share choosing farm raised beef to 80%. Environment and technology information had minor effects on conditional market shares but reduced the share of people not buying any meat (alternative) options, indicating information pulled more people into the market. Even if plant- and lab-based alternatives experienced significant (e.g., 50%) price reductions, farm raised beef maintains majority market share. Vegetarians, males, and younger, more highly educated individuals tend to have relatively stronger preferences for the plant- and lab-based alternatives relative to farm-raised beef. Respondents are strongly opposed to taxing conventional beef and to allowing the plant- and lab-based alternatives to use the label “beef.” ”

We show that even at significant discounts, most people prefer conventional beef. The following demand curves for each of the products illustrates.

A couple weeks ago, I weighed in on the debate about whether these new products can or should be labeled “beef” or “meat.” It seems the U.S. public is far more certain on this than I was.

More details are in the paper.

Because these are new products just hitting the market, it is possible that these preferences can and will change, particularly when more consumers are able to taste them. However, at present, the future market potential for these products appears to fit more in the “niche” category, even at significant price discounts. What will happen in the future? Only time will tell.