Even casual followers of economics understand the concept of externalities. An externality arises when an individual does not consider the cost of their actions on other people. A classic example is a factory that does not consider the cost of their pollution into nearby streams or rivers when setting the price of their outputs. While the concept of an externality is fairly clear, what to do about it is less so (see this piece I wrote back in 2013), but typical answers include everything from assignment of property rights and negotiation to so-called Pigouvian taxes. The externality argument has been used extensively in food debates to argue various food stuffs are “too cheap” and that items like sodas or meat or ingredients like sugar, fat, or calories should be taxed.

I won’t re-has all the pro- and con-arguments for these taxes here, except to say that the common claim that we need to re-consider the “true cost of food” because the externality consists of impacts on Medicare or Medicaid is much less obvious than is typically presumed. The point of this post, rather, is to note that I’m starting to see a new argument enter the debate. Apparently, drinking soda not only causes externalities, but it also cause internalities.

What is an internality? An internality is thought to arise when an individual does not consider the cost of their current action on their future self. This article by Allcott, Lockwood, and Taubinsky in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 2019 derives theoretical conditions for optimal soda taxes when there are externalities and internalities. As empirical evidence of the presence of internalities, they show that consumers who score higher on a nutrition knowledge test consume less sugared soda than consumers who score lower on the test. They calculate that if all consumers had the same knowledge as that of trained nutritionists, the average U.S. household would consume 31% fewer sugar sweetened beverages. They calculate that, on average, sugared beverages would need to be roughly 1 cent per ounce higher to induce people to consume an amount equal to what they’d consume if they had the same knowledge as a trained nutritionist.

Moreover, because lower income consumers tend to score worse on nutrition knowledge tests, Allcott et al. argue that lower income consumers suffer from greater internalities than higher income consumers. As such, their logic is that a soda tax is not regressive as is typically assumed (since lower income consumers spend a higher share of income on food), but rather these taxes are helpful in “correcting” the lower income consumers’ lack of knowledge as compared to higher income households. In fact, a soda taxes is now thought to be progressive because there is greater “correction” needed for lower income households’ purchases.

The concept seems to be catching on. Earlier this year, Dubois, Griffith, and O'Connell published a paper in the American Economic Review where they conduct some interesting and careful analysis to determine what types of households would be most affected by a soda tax (there are a lot of interesting results in their paper; I encourage you to check it out). Their baseline result seems to confirm the conventional intuition that soda taxes are regressive (i.e., primarily borne by lower income households). According to the paper:

“We show that compensating variation [the economic welfare losses] associated with a tax on sugary soft drinks is around 20 percent higher for those in the bottom half of the distribution of total annual grocery expenditure (a proxy for income) compared with those in the top half.”

However, after assuming tax revenues are redistributed back to consumers in a lump sum, and employing Allcott et al.’s estimate of the benefits from reduction in internalities, they are able to conclude that soda taxes are (from the abstract):

“unlikely to be strongly regressive especially if consumers benefit from averted internalities.”

I’m a little unsure what to make of the rise of the internality argument as a justification for soda taxes. On a visceral level, it strikes me as paternalistic: “These poor people just don’t know what’s good for them. Experts are here to help.” That’s probably a bit harsh. We have plenty of evidence that people make mistakes; the whole field of behavioral economics rests on this notion (though, as I argue here, it need not justify new regulation).

Though neither of these papers make the link, this work is very similar to the area of literature on the “value of information” (I discuss much of that theory here). The basic idea is that if people change their purchases when they are more informed, then there is value in the information. Or, rather, there would be a “cost” to forcing people to buy what they did in ignorance now that they know more.

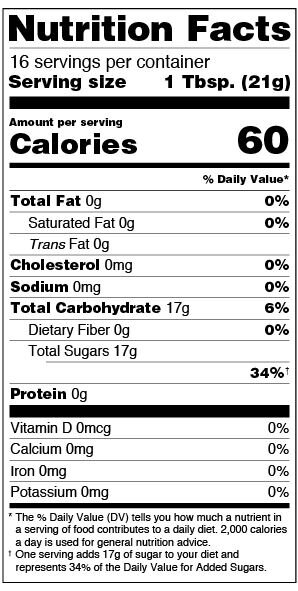

All this is a way of saying: if people suffer from the kind of internality discussed above: why is the right policy response a tax rather than information disclosure or education? Do we have any good studies on how people’s soda consumption changes after being exposed to information on health consequences? How does the “value of information” estimate from those sorts of studies compare to the internality estimates? I’d also note that sodas contain a nutrition facts panel, so the calorie consequences are clearly available for those willing to look. (For those who are interested, here is a seminal paper on the value of information contained in nutrition facts panel by Teisl, Bockstael, and Levy; they also tend to find a higher value of information for lower educated consumers).

I also can’t help but wonder how people would feel if we applied the internality argument to other areas where we know people make choices with objectively false beliefs? Let me give two examples from papers I’ve co-authored just this year.

First, consider this paper co-authored with Ruoye Yang and Kelly Raper. We find that the median consumer thinks 55% of hogs and 57% of chickens raised in the U.S. are given added growth hormones to promote growth. The truth? Zero. Use of added growth hormones is not allowed with these animals. The trouble is that these mis-perceptions distort demand. The results from one of our pooled models suggests that a person who correctly knows the answer is 0% is willing to pay $0.92/lb more for pork or chicken than someone who incorrectly believes the answer is 100% hormone use. According to the internality argument, we’d need to subsidize pork products by $0.92 *0.55 = $0.51/lb to induce the median consumer (who incorrectly believes 55% of pork has added hormones) to consume the same amount of pork as someone with correct beliefs.

Another example is my paper with Lacy Wilson in Food Policy on redundant labels. We find 47% of consumers are willing to pay a premium for non-GMO salt and 41% are willing to pay a premium for gluten free orange juice. These are almost certainly “mistakes”: there is no DNA in salt (and thus it cannot be a GMO) and there is no gluten in oranges. Additional analysis also bears out the fact that these are choices made in ignorance. People who have farm work experience and who have higher scores on a scientific literacy quiz tend to have lower willingness-to-pay premiums for these redundantly labeled products. We find that a person who got a perfect score on our scientific literacy quiz is willing to pay about $0.30 less for a bottle of “gluten free” orange juice than is someone who missed all the questions in the quiz. According to the internality logic, we need to tax orange juice with a gluten free label $0.33 to induce people with the low scientific literacy to consume the same amount of “gluten free” OJ as people with the highest scientific literacy.

How would advocates for an internality-based soda tax feel about advocates for an internality-based pork subsidy or a gluten free orange juice tax? I might imagine an argument that goes something like the following. Well, excessive soda consumption is going to cause real health care costs in the future that people need to consider now; that’s not comparable to “superfluous” harm of over-paying for non-GMO salt or gluten free orange juice or under-buying pork and chicken. But, not everyone who consumes soda will suffer future adverse health consequences and yet all would have to pay the internality tax. By contrast, virtually everyone who pays a premium for hormone free pork or chicken or non-GMO salt is overpaying now. People foregoing pork or chicken because they mistakenly believe these products contain added growth hormones are foregoing those pleasures now. Moreover, these magnitudes can add up across people and over time. For some context, total retail pork expenditures in the U.S. were in the ballpark of $62 billion last year. If there were even a 1% adjustment in purchases because of incorrect beliefs, it would represent a swing in spending of $600 million.

It is clear internalities exist, but I’m less convinced they represent solid justifications for tax/subsidy policy. For one, it’s a slippery slope. As I’ve illustrated above, there are likely lots of things we know very little about and where the “experts” would exhibit different preferences and beliefs than the lay person. Thus, the scope for internality-based taxes strikes me as nearly limitless. There’s also the issue of whether we in fact know enough to focus people’s attention on the “right” things.

While taxes are likely have a more direct and immediate effect on consumption than information policies, my sense is that, philosophically, the right approach to a lack of information is information provision, not taxes. Nonetheless, one must acknowledge, even if you give people the objective information, as my paper with Lacey shows, it simply isn’t the case that everyone will suddenly agree on the same level of consumption. This also suggests, however, a potential flaw in the way these internalities are calculated; we can’t just assume people with high vs. low nutrition knowledge or scientific literacy are or will behave the same in every other respect except for their nutrition knowledge or scientific literacy no matter how many controls we add to our analysis.