Remember the long running campaign by the Pork Board?

The campaign pitching pork as the other white meat made sense at a time when there was rising concern about fat content and red meat consumption and increased competition from chicken. But, times have changed.

One of the changes has come about from scientific developments. As it turns out, pork color is a good indicator of eating quality, and in blind taste tests, consumers prefer redder pork to whiter pork. Do consumers know this? Could a quality labeling system help coordinate the pork supply chain and better align production with consumers' eating expectations?

These were the questions that led to this paper just released by the journal Food Policy that I co-authored with Glynn Tonsor, Ted Schroeder, and Dermot Hayes with funding by the National Pork Board (a longer report of the results is here).

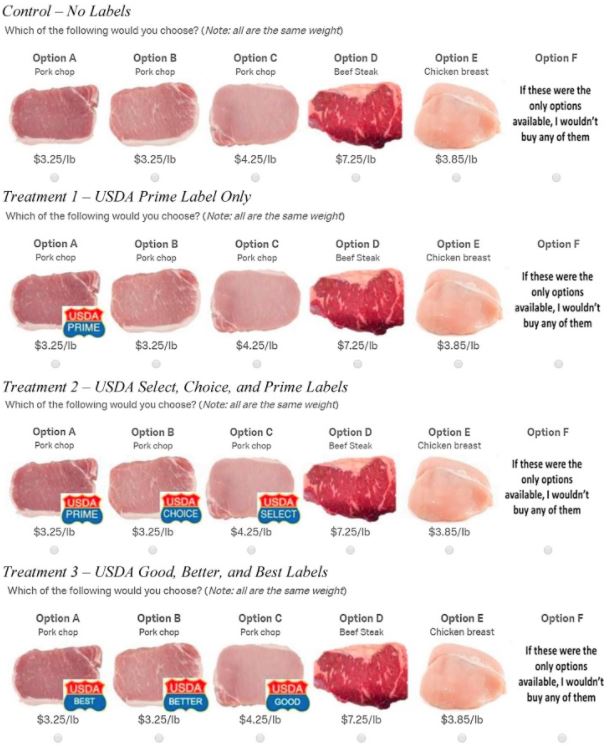

We surveyed about 2,000 consumers for the analysis reported in the Food Policy paper. We were mainly interested in how consumers' choices between pork (and other meat) products varied with the color of the pork and whether and which kinds of labels were present. Consumers were randomly assigned to a control (with no labels) or one of several treatment groups that utilized different labeling systems. Below shows a particular choice question used in the various treatments.

We use the choices consumers made in these treatments to back out consumers' willingness-to-pay, but even more importantly, the probability a consumer buys any type of pork and the expected revenue from pork. For the economists out there, I'll note that we also have some methodological innovation. Rather than just looking at the probability of buying a type of pork at a given set of prices, we also invert the equations to look at the equilibrium price of pork at a given quantity of different types of pork (this is important because in the short run, pork producers can't easily produce a larger amount of higher quality pork).

So, what did we find?

We find:

“In the absence of a cue in the “no labels” control, on average, participants do not differentiate among the three quality levels [or pork colors]. There is no significant difference in average WTP [willingness-to-pay] for the three different colored chops. This is consistent with industry interest in adding quality labels to facilitate further separation of pork quality by consumers. The introduction of a single Prime label for the highest quality chop in Treatment 1 results in a significant increase in the WTP for the chop that would carry the highest quality grade; however, there is a significant reduction in WTP for the lower quality chops that did not carry labels in this treatment. ... When all pork products have grade labels, there is a significant premium for higher vs. lower quality pork and total pork sales rise, as do expected revenues. This can be seen in [the figure] as the mean WTP estimates for all pork qualities lie above those in the control condition with no labels.”

We go on to show there is significant heterogeneity in consumer preferences. We find that 28% to 40%, depending on the labeling condition, of consumers prefer white pork to red pork.

From the conclusions:

“The choice experiment data analysis suggests that a USDA grade using Prime, Choice, and Select or Good, Better, Best labels would be most likely to increase expected pork revenue and the probability of purchasing pork. Additional important opportunities are present within this strategy. Foremost is that even with quality labels on the pork chops, a significant fraction of consumers preferred lower quality than Prime even when the three quality products were priced the same. Such consumers either do not understand the quality grade rankings of Prime, Choice, and Select (though results were similar for Best, Better, Good, which should be less prone to confusion), or this group of consumers were ignoring the quality grade labels and relying on product color to influence their choices. A possible response would be to segment consumers and to use the grading system only on those consumers who prefer red chops. Segmentation could be done by exploring preferences across states, institutions, income categories, ethnicity, and by export market. Despite the possibility for segmentation, however, we show, that if all qualities are present, only labeling the highest quality is likely to reduce total pork sales and revenue”

As this piece in the Federal Register indicates, the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service is seeking public comment on the usefulness of such a labeling system. Maybe one day in the future you will see new pork quality grade labels in the grocery store.