The journal Food Quality and Preference just released a new paper I co-authored with Jisung Jo, a former student who now works at the Korea Maritime Institute.

Here is the motivation for the work:

“One of the key mechanisms policy makers have utilized to encourage healthier eating is the provision of information via nutritional labels. However, research has shown that the provision of health information does not necessarily increase consumption of healthy foods ... A possible reason for the largely ineffectual impact of nutritional labeling might be because health information not only updates consumers’ health perceptions but also affects other perceptions, such as taste and affordability, which are the primary drivers of consumer purchase behavior ”

In other words, if you see a new labeling indicating a food is healthier than you previously thought, do you now think it will be less tasty? Or more expensive?

To explore this issue, we surveyed consumers in three different countries (US, China, and Korea). We showed consumers a picture of a food item and asked them to rate the item, on simple scales, in terms of perceived taste, health, affordability, and purchase intention. We did this for 60 diverse food items. Then, the ratings of all 60 foods was repeated after the subjects had received information about each food item’s healthiness, which was conveyed via a "traffic light" labeling system (green=healthy, yellow=medium healthiness, red=unhealthy). Here's an example of one of the questions asked before and after the information:

Unsurprisingly, the provision of "green" labels tended to increased perceived healthiness and the provision of "red" labels tended to reduce perceived healthiness. Of more interest is how these labels affected perceptions of taste, affordability, and ultimately purchase intentions.

Unexpectedly, we found that providing information that a food was healthier than people previously thought tended to increase perceived taste. People also tended to think items that are less healthy than previously thought will ultimately be less expensive.

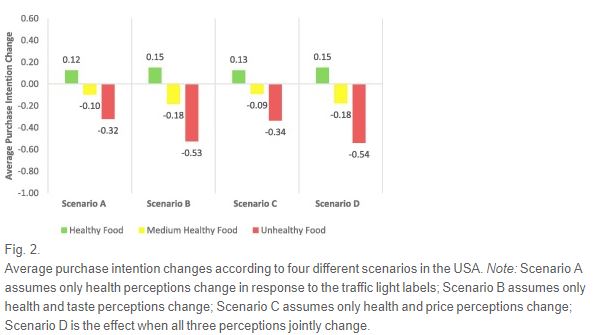

We created the following graph to look at how projected changes in purchase intentions (after provision of health information) would change if one ignores the fact that health information also affects perceived taste and affordability.

“Across all scenarios and in all three countries, we find that negative health information has the biggest effects on purchase intention changes. Intriguingly, the average purchase intention in scenario B is larger than that in scenario A. The values for scenario D are the same as the actual average of purchase intention (since they are just the model evaluated at the mean effect changes of all variables included in the model). Comparing the purchase intention changes as one moves from scenario A to D shows the effect of ignoring integrated health-taste-affordability perceptions.”

Overall, this research underscores the need to understand how labels which convey health information might also alter other perceptions related to taste and affordability.