The words "unprecedented” and “uncertain” are being thrown around a lot these days, and it is precisely because the words have never been more true. I’ve been positing on happenings in the meat and livestock markets in the wake of COVID-19, and thought it might be useful to try to illustrate just how unusually volatile these markets have been.

Consider the weekly changes in wholesale met prices (all data are from the USDA compiled by the Livestock Marketing Information Center). Below are weekly changes in pork prices over the past decade. For the week ending April 4, 2020, wholesale pork prices were down $16.32/cwt (or $1.63 per pound). This is the largest change in wholesale pork prices since at least the year 2000 (I haven’t looked at data prior to that). However, just two weeks prior (the week ending March 20, 2020) wholesale pork prices were up $7.58/cwt. This was the largest weekly increase in the past decade. So, within a three week time period, we’ve witnessed the 3rd largest weekly price increase and THE largest weekly price decrease in at least a decade.

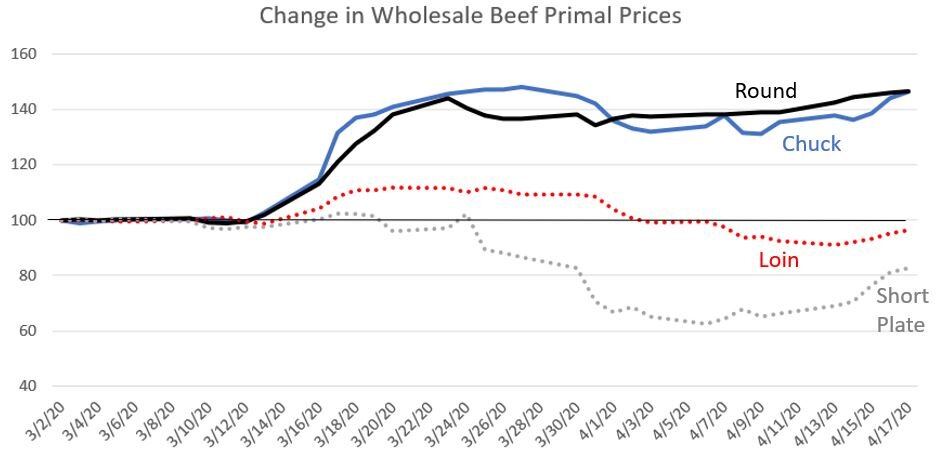

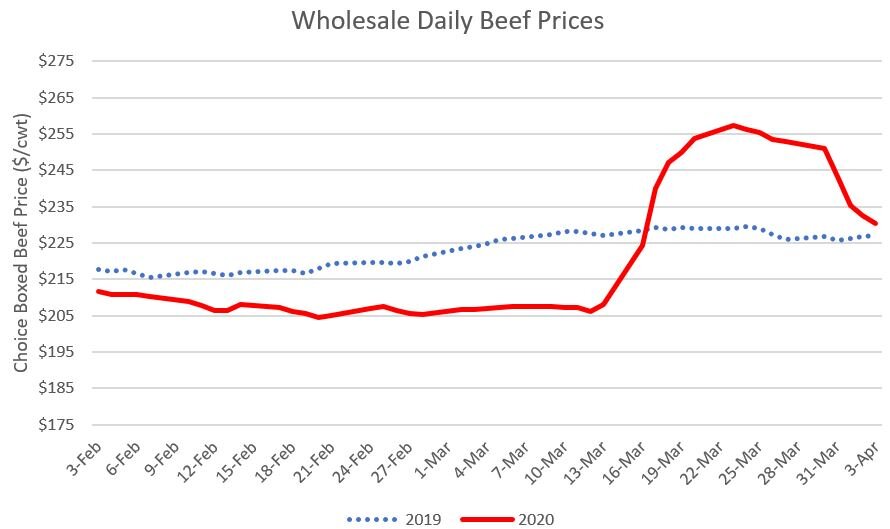

We see a similar outcome for beef. For the week ending March 20th, 2020, we witnessed the largest weekly increase in the wholesale price of beef (an increase of $35.88/cwt) we’ve seen in at least a decade. And just two weeks later, the price fell $16.58/cwt, the largest weekly price decline in at least a decade. Prices fell again $13.10/cwt the following week, for the 3rd largest weekly price decline in a decade. Within a three week time period, we’ve witnessed THE largest weekly price weekly increase and THE largest weekly price decrease in at least a decade.

I’d call that volatile!