I recently completed a new study for the Plant Based Product Council exploring consumer understanding and attitudes toward bio-based labels and claims.

Given the lack of harmonization and potential public confusion around terms used to describe the bioeconomy, a survey was designed to to determine consumer knowledge, beliefs, and preferences for the following 10 terms: biobased, biodegradable, bioeconomy, bioplastics, biopolymer, circular economy, compostable, organic, plant-based, and recyclable. I conducted a nationwide survey of about 1,500 U.S. residents to explore these issues (note: topline results reporting the share of respondents falling in every response category for every question asked in the survey is provided here).

Here are some of the key findings:

Self-assessed, subjective knowledge of bio-based related terms is low. About half the public has never heard the terms biopolymer, circular economy, or bioeconomy; more than half have either not heard or indicate not knowing the meaning of the terms biobased and bioplastics. By contrast, a majority of respondents said they were either somewhat or very knowledgeable of the terms: recyclable, organic, plant-based, biodegradable, and compostable.

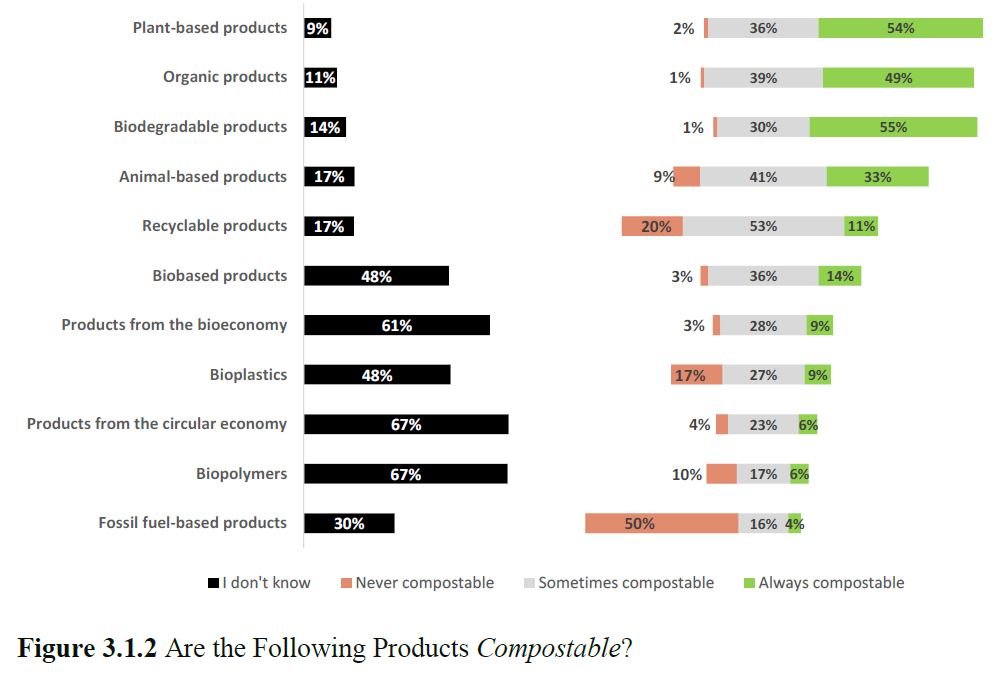

Generally, respondents indicated ignorance in knowing whether products that were biopolymers, bioplastic, biobased, or from the circular economy or bioeconomy were or could be recyclable, compostable, or organic.

Responses to true/false and definition-matching questions reveal wide dispersion across the public in objective knowledge of bio-based and related terms. Only 0.6% of respondents answered 90% or more of the questions correctly. Forty six percent of respondents answered more questions incorrectly than correctly, and another 11% answered as many questing right as wrong. For example, only 27% of respondents correctly indicated it was false that “All biodegradable products are compostable.”

More respondents than not provided incorrect definitions for biodegradable, compostable, organic, and biobased. Respondents were particularly likely to mistake the definition of biodegradable for composable, biobased for organic, and plant-based for biobased. White, non-Hispanics, middle-aged, higher educated individuals, particularly those with graduate degrees, exhibited higher objective knowledge of biobased and related terms, on average, than non-white, young, elderly, or people whose highest education was a high school degree.

Compostable, plant-based, organic, biodegradable, and recyclable products were perceived to be high in sustainability and environmental friendliness; the opposite was true of animal-based and especially fossil-fuel based products. Recyclable and compostable products were viewed as relatively affordable whereas organic products were not. Recyclable products were perceived as relatively low in quality whereas organic was perceived as high quality.

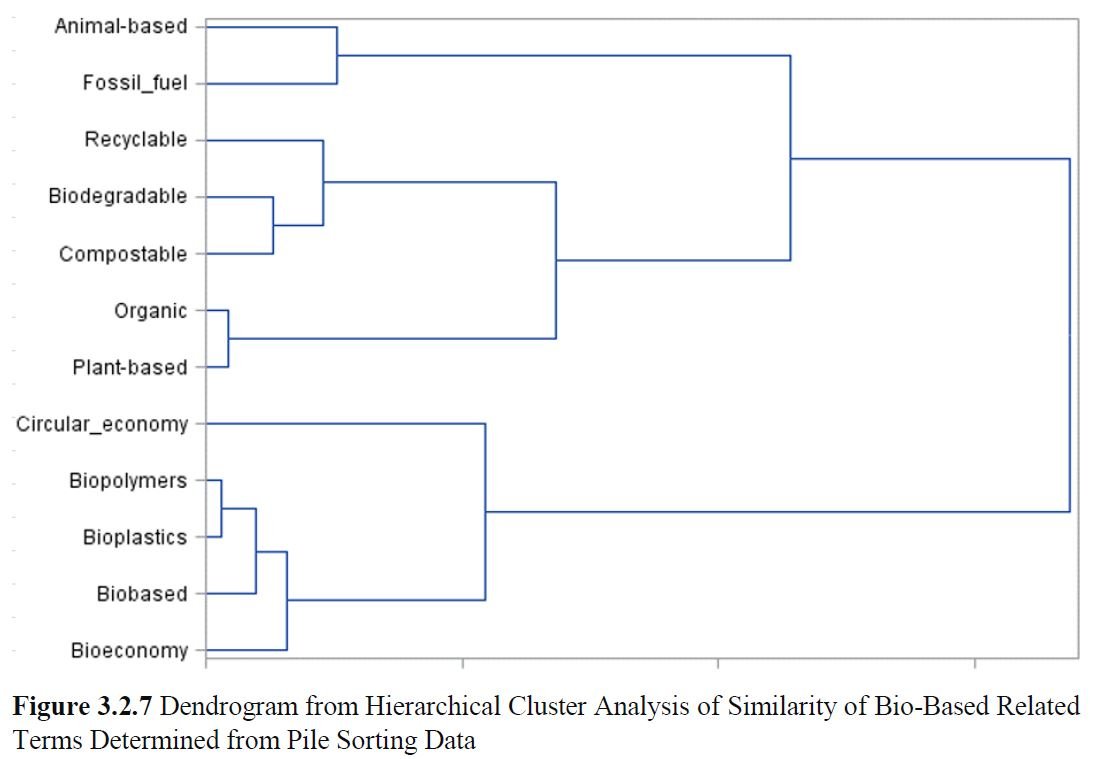

Perceptually, respondents tend to view terms like organic and plant-based as being highly similar and related to another grouping of perceptually similar terms: biodegradable, compostable, and recyclable. Perceptually, respondents view all other terms with a “bio” prefix similarly: biobased, biopolymer, bioplastic, bioeconomy. Terms viewed as most dissimilar to the rest include circular economy, fossil-fuel based, and animal-based.

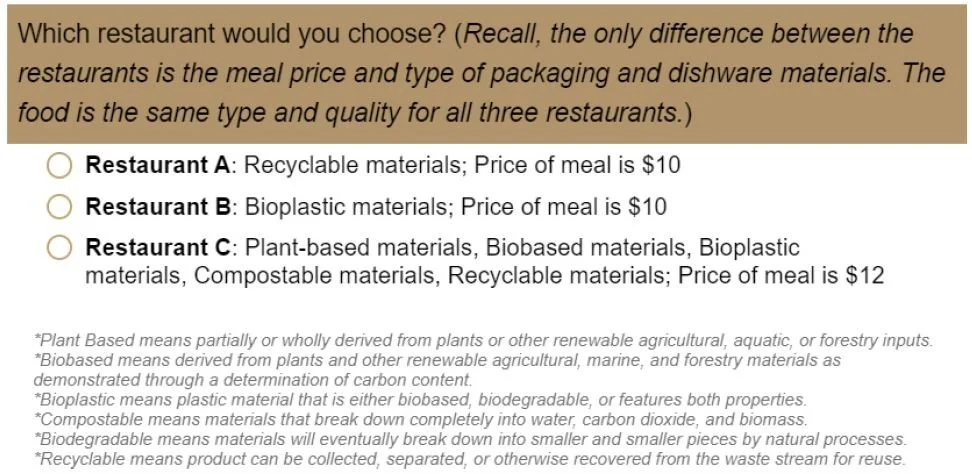

Simulated shopping choices indicate respondents are willing to pay significant premiums for take-away food in compostable, plant-based, or recyclable packaging while placing discounts on biobased and bioplastic packaging. Preferences for plant-based, compostable, and bio-based packaging are heavily influenced by the presence/absence of other label/claims, indicating consumers view these terms as having strong complementarity or substitutability relationships with other labels/claims.

Choices are significantly impacted by disclosures providing definitions of label terms. Providing definitional disclosures increased willingness-to-pay and choice likelihood for compostable packaging while having the opposite effect for biodegradable packaging, at least when these labels appeared in isolation.

Providing definitional information tends to reduce the size of the preference interactions between labels. When packaging already contains many competing claims/labels, provision of information disclosures increases the value of adding a new biobased claim in all instances. However, when adding a single label/claim in the absence of any others, definitional information reduces willingness-to-pay and choice probability for four terms (biodegradable, recyclable, plant-based, and biobased) while increasing it for two terms (bioplastic and compostable). These findings indicate definitional information tends to cause respondents to be more likely to

You can read the whole report here.